The Witness builds a scale model of the inquiring mind

Line puzzles and the aesthetic experience of thought

Spoiler warning for puzzle mechanics and certain solutions in The Witness

When Jonathan Blow set out to make a video game about the experience of thinking, he chose as his form the labyrinth.

This was to be Blow’s second game. He found himself with the means and reputation to pursue any project he wanted. His first game, Braid, was a smash hit when it was released in 2008. A puzzle platformer, it used a variety of time-manipulation mechanics to brain-wrinkling effect and set off the indie game boom that has in large part defined the last two decades of the medium.

The Witness, released in 2016, takes place on an island. The colors are hyper-saturated, the sun is bright, everything except the water lapping the shore is perfectly still. You can almost feel the thick, slightly humid air on your skin as you explore. In classic video game fashion there are a number of different biomes—desert, swamp, thick jungle, snowy mountain—that abut one another in ways they never could in real life. Strewn everywhere on the island are screens, often grouped into sequences. Each screen displays a maze puzzle. In the tutorial area they are literally just mazes—move your cursor from the starting point to the end point to solve it. After that certain conditions need to be met for that line to trace a valid solution. Each zone on the island centers on a different rule. Some are environmental, such as the autumn forest where you must follow the twisting shadows of the tree branches overhead that become progressively more tangled and obscure. And some are purely logical, such as the stars that want to be separated out into sets of two or the “tetris block” puzzles that require you to trace specific shapes.

Each of these rules are taught by a set of elementary puzzles that demonstrate it at its most basic and then scale up the complexity. Here’s the first set of screens a new player encounters, which I asked Liz to play in order to show the authentic process of someone working through these puzzles for the first time:

I know none of you watched that video in full (it’s fine!) because watching someone else try and fail to solve maze puzzles for ten minutes is boring, but to the experienced eye there’s a lot to appreciate. Over the course of a few boards you can see my wife’s play change significantly. When she gets stuck on the fourth puzzle she tries to brute force it. Still not quite seeing the rule governing these panels, she is guessing; she checks every answer to see for sure that it’s wrong. By the last few, you can see her pause and backtrack when she realizes a line isn’t going to work; she has become more thoughtful, and confident in her own judgments. She also quickly masters certain fundamental maneuvers, like tracing along the outside first when she needs to loop back.

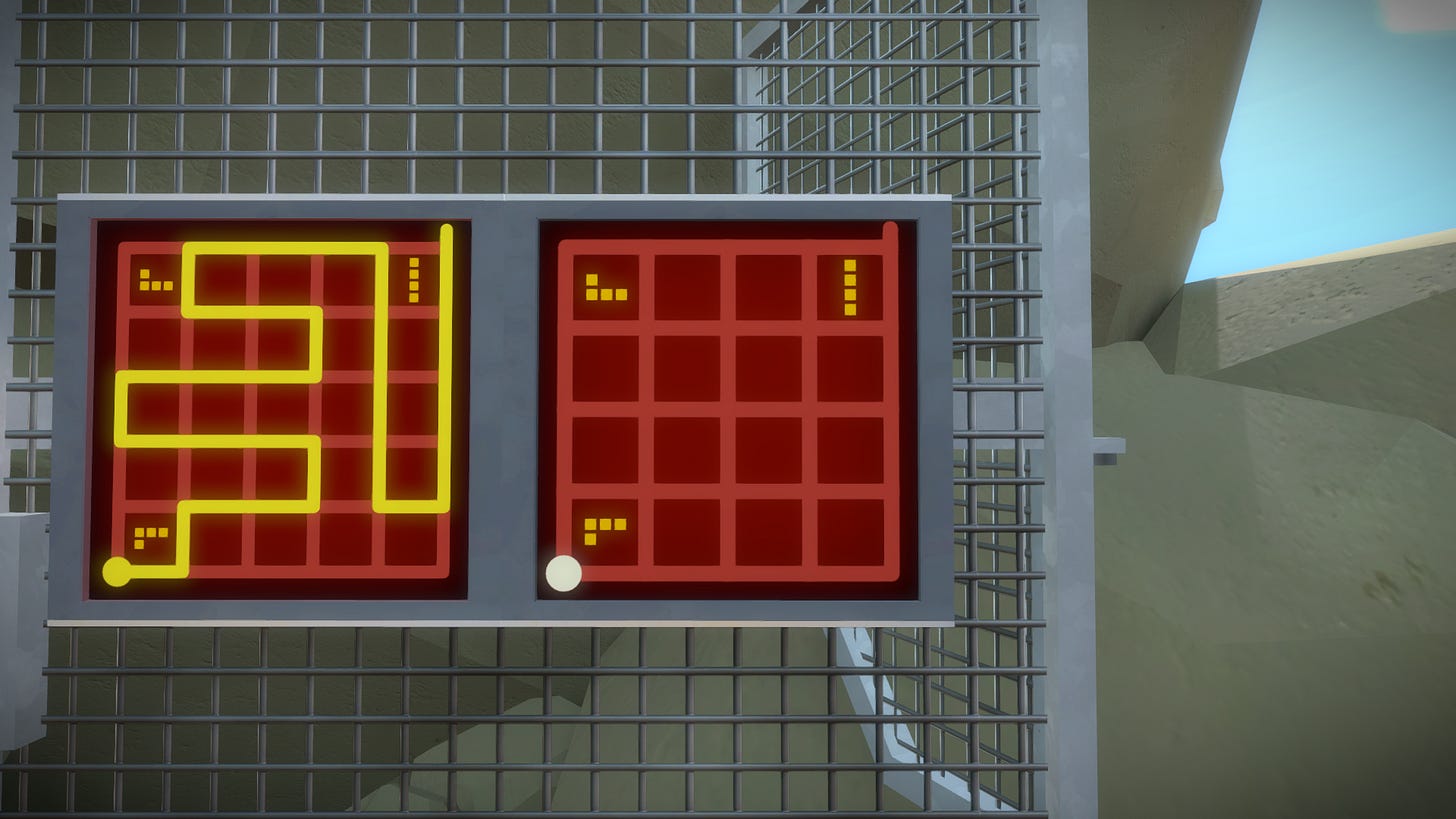

Let’s look at one of the tetris shape puzzles, which for me tend to be the hardest to wrap my head around. Judging from other people asking for help online, this is one of the biggest stumpers of the mid-game:

Can you solve it? One key principle of the shape puzzles is that multiple shapes can be grouped into one larger mass. And crucially, the shapes can take any position within that aggregate—that is, in this puzzle for instance, that vertical four-long does not need to stay with the square it’s pictured on, so long as that square is part of the overall shape containing all the sub-shapes. You still with me?

Okay, here’s the solution:

Do you see it? The pieces have been switched around but they’ve all retained their original orientation. Let me make it a little clearer:

As you can see, none of the pieces are where their symbol is. I have a hell of a time holding the grid position of multiple shapes in my mind at the same time when they’re all being rearranged so I often resort to more analog solutions:

This puzzle is actually exceptionally easy. All the pieces go basically right where their symbols are. It’s just more information than I can keep track of mentally. I wish I had my notebook from my first playthrough of The Witness from ten years ago; I filled pages and pages more than I did this time around. I guess that means I’ve gotten smarter?

The Witness provokes a sort of thinking that is deviously hard to describe. As one draws their lines looking for the correct path, there is reasoning happening. But, for me at least, it is a reasoning not happening in language. This reasoning occurs in a non-verbal form of logic, rules articulated non-verbally by the maze and the solution articulated non-verbally by the line. All the intervening false starts and wrong solutions are attempts to work through that logic on a level totally distinct from any sort of linguistic step-by-step, if-then sort of thinking. The board sits before you, its logic visible in its entirety. Once the correct path is laid in, it looks so simple, so elegantly obvious, it looks like it’s been there forever. To work through a Witness puzzle is to experience a strange temporal disjunction as our time-locked minds struggle to encompass a form of logic that is fully present all at once.

When asked what he hoped players would take from the game, Blow himself highlighted as important that it prompts a mode of thinking outside of language: “It’s so big and complicated they can take away what they want, honestly,” he said. “But I do think there is a certain flavor the game has that will come across to most people most of the time. It’s hard for me to verbalize what that is—it’s something about the non-verbal communication and exploring the world freely, and having this experience of epiphany over and over where you go from not understanding to understanding, repeated over and over.”

Given time and practice, these problems can become second nature. We can learn to read these mazes in moments. I swear this clip shows the first time I set eyes on this puzzle.

Call me Piranesi. At this point I am fully at home within the rules of the labyrinth. The labyrinth has become my world and my thoughts follow its nature.

For a game whose action takes place mostly in our minds, Blow could hardly have found a better image than the labyrinth. The labyrinth is an ancient trope that never fails to spur our mind to seek a solution. To be in a labyrinth is to be trapped and lost, but rather than the despair of a prison cell, the labyrinth demands we get up and move—we must find our way through. In my new favorite book The True Story of the Novel, Margaret Anne Doody discusses labyrinths at some length. She writes:

Above all we notice the intricacy. The Labyrinth is associated with anxiety, with puzzlement, with strained attention. It presents an epistemological challenge. How is one to disentangle what is confused, how to locate a meaning and hence an objective? In heightened uses of the Labyrinth Trope, epistemological and moral problems of great force are represented in emblems of spatial disorientation, of the self in unknown space.

The experience of the Labyrinth is not essentially, as with cave or tomb, enclosure, but wandering through an obscure suite of enclosures that are also openings, opportunities. The mind must always be busy calculating these intricacies. Unlike the prisoner, or the patient buried alive, the lost one in the Labyrinth is a traveler and must keep on the move to survive. The attention is dizzied by the constant fissioning, one thing leading to another in an associative scramble very like the mind itself.

The mind is a labyrinth of its own. The process of thinking is a process of finding our way past the dead ends and wrong turns as we hunt for a complete thought. But we seek to escape the labyrinth. If our mind is one, our ultimate goal is then to escape the limitations of our thoughts and emerge into the fullness and freedom of unimpeded understanding.

In his 2020 book Games: Agency as Art,1 C. Thi Nguyen argues that the unique value of games (all kinds, not just video games) lies in their ability to generate aesthetic experiences of our own actions. Unlike elsewhere in life, we take up a goal and a set of restrictions (rules) not for the sake of accomplishing that goal, not really, but for the sake of the struggle that ensues trying to reach it. If we play a game of basketball with friends we take on the goal of putting the ball through the hoop not because there’s any intrinsic, external value to doing so but because that goal is a necessary condition of playing basketball, which we want to do for the experience of playing basketball.

The aesthetic aspect comes in when the game, through its vast simplification of the world and our actions, allows us to match our abilities to the task and to enjoy the elegance and grace of what we ourselves are doing. I thought immediately of Celeste and wished I had read the book before I wrote about it. Celeste captures everything Nguyen is talking about. Both for Madeline within the narrative and for us as players, the goal of summiting the mountain is not the point. The point is the struggle to get there. And why is that struggle so satisfying? Why did I subject myself to so many, many deaths? Because the satisfaction of overcoming those challenges is second to none. Specifically, pulling off that correct series of dashes and jumps is aesthetically satisfying—there is a grace in Madeline’s movements, a grace that I am responsible for. I see beauty in a perfectly executed wavedash.

Nguyen writes:

Consider the difference between two superficially similar activities: dancing and rock climbing. Dancing freely can be an aesthetic experience. My own movements can feel to me expressive, dramatic, and, once in a rare while, even a bit graceful. I also rock climb, and rock climbing is full of aesthetic experiences. Climbers praise particular climbs for having interesting movement or beautiful flow. But, unlike many traditional forms of dance, climbing aims at overcoming obstacles. The climbing experiences that linger most potently in my mind are experiences of movement as the solution to a problem—of my deliberateness and gracefulness that got me through a difficult series of holds…

This, it seems to me, is a paradigmatic aesthetic experience of playing games. Once we’ve seen it, we can see that aesthetic experiences with this character exist outside of games. I value philosophy because I value truth, but I also savor the feel of that beautiful moment of epiphany, when I finally find that argument that I was groping for. Games can provide consciously sculpted versions of those everyday experiences. There is a natural aesthetic pleasure to working through a difficult math proof; chess seems designed, at least in part, to concentrate that pleasure for its own sake. In ordinary practical life, we catch momentary glimpses, when we are lucky, of harmony between our abilities and our tasks.

As Blow said above, The Witness is a machine that generates epiphanies. Perhaps the most impressive achievement of Blow’s design is the sequencing and difficulty curve of the puzzles. In each area, and in the game overall, we find ourselves perpetually confronted by yet another board that is just slightly beyond our quick intuition. We think we see an obvious solution but as we draw it out we see what’s wrong. Oh. What looked so straightforward is quite a thorny problem. We get stuck. We stare. We trace half a path and stop. We declare the puzzle unsolvable. And then—there it is. We didn’t see it before. How couldn’t we? There it is. It’s so clear. A rush. Our mind expands just a little bit more. Next puzzle. Repeat.

What Blow has done, to use Nguyen’s wording, is sculpt an experience that draws out the aesthetic pleasure of our mind at work. Learning in real life is often a slow and diffuse process—learning a language, for instance, requires investing in the separate skill trees of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. It takes a long while and a lot of persistence before they coalesce into any real facility with the tongue. It can be hard to marshal one’s full abilities to a mental task, pulled as our attention always is by the myriad practical concerns of our lives. Real inspiration just doesn’t strike every day.

In real life, our solutions can be murky, only half satisfying. An argument has a gap we can’t quite figure out how to bridge. That quote we were counting on in Dante just isn’t there. Perfect answers aren’t available, or we lack to ability to articulate them. The Witness gives us back the satisfaction of arriving at the full clarity we crave but can so rarely find. It shows us the feeling the great thinkers of history were chasing when they devoted their lives to building philosophical systems and unearthing the properties of the natural world.

As the player explores the island, they will happen upon little tape recorders tucked away at the foot of a statue or on a ledge overlooking the sea. There are 49 in total to find. Each one, when clicked on, plays a reading of a quotation from a notable thinker. These range from contemplations of God by Augustine and Nicholas of Cusa; Eastern philosophy and zen; and modern science, with passages from Albert Einstein and Richard Feynman. The readings circle a few common themes. One is struck by the similarity of language between the men of science and the men of faith, how they are united by their desire to know, their acceptance of the impossibility of full understanding, and their happy resignation to continue trying.

Feynman speaks of the (wonderful, hard fought for) role doubt and uncertainty plays in the scientific method. Nicholas of Cusa marvels at God’s absolute beyond-ness and his learned ignorance:

O Lord God, helper of those who seek you, I see you in the garden of paradise, and I do not know what I see, because I see nothing visible. I know this alone that I know that I do not know what I see and that I can never know. I do not know how to name you, because I do not know what you are. Should anyone tell me that you are named by this or that name, by the fact that one gives a name I know that it is not your name. For the wall beyond which I see you is the limit of every mode of signification by names. Should anyone express any concept by which you could be conceived, I know that this concept is not a concept of you, for every concept finds its boundary at the wall of paradise. Should anyone express any likeness and say that you ought to be conceived according to it, I know in the same way that this is not a likeness of you. So too if anyone, wishing to furnish the means by which you might be understood, should set forth an understanding of you, one is still far removed from you. For the highest wall separates you from all these and secludes you from everything that can be said or thought, because you are absolute from all the things that can fall within any concept.

Einstein’s quotations are the linchpin. He discusses the cosmic religious feeling that powers scientific investigation:

I maintain that the cosmic religious feeling is the strongest and noblest motive for scientific research. Only those who realize the immense efforts and, above all, the devotion without which pioneer work in theoretical science cannot be achieved are able to grasp the strength of the emotion out of which alone such work, remote as it is from the immediate realities of life, can issue. What a deep conviction of the rationality of the universe and what a yearning to understand, were it but a feeble reflection of the mind revealed in this world, Kepler and Newton must have had to enable them to spend years of solitary labor in disentangling the principles of celestial mechanics!

Those whose acquaintance with scientific research is derived chiefly from its practical results easily develop a completely false notion of the mentality of the men who, surrounded by a skeptical world, have shown the way to kindred spirits scattered wide through the world and through the centuries. Only one who has devoted his life to similar ends can have a vivid realization of what has inspired these men and given them the strength to remain true to their purpose in spite of countless failures. It is cosmic religious feeling that gives a man such strength. A contemporary has said, not unjustly, that in this materialistic age of ours the serious scientific workers are the only profoundly religious people.

Other quotations are parables, thought experiments, enigmatic aphorisms. From disparate times, continents, and traditions, they are all aimed at the same goal: the endless quest to make sense of the world. The toolkit varies wildly but the goal and the struggle remain the same.

There comes a moment for every player of The Witness. They are wandering around the island and suddenly some feature in the landscape strikes them with newfound significance. It might be a ripple in the sand, or some puffy clouds, or a drainpipe. With a start the player notices these parts of the physical world are shaped exactly like one of their maze lines—circular start point and rounded tip. They click on it, just as a gag. The object flares to life with glowing particles. They move their cursor to the end and click. The glow explodes and shoots off into the sky. The player looks around the landscape as if for the first time. Suddenly they realize they are surrounded by these shapes, hidden everywhere, waiting to be discovered.

It’s in this moment The Witness stops being a fun and frustrating game about line puzzles and becomes something more. Primed by the audio logs we understand that we are engaged in the same project as those titans of thought whose words we’ve heard. In the little snowglobe world of the island we are scientist and theologian testing hypotheses and accumulating knowledge on the screens and using it to bring coherence to the surrounding world.

Nguyen argues that our library of games can be understood as a library of agencies. That is, every game offers a unique mode of interacting with the world, a lens that focuses our practical reasoning toward the task at hand. Chess encourages an analytical approach that looks many moves ahead. The party game Werewolf makes us play the bullshitting sophist or an attentive bullshit detector depending on whether we’re a wolf or a villager. Nguyen thinks exploring and expanding our library of agencies is immensely valuable. By playing games we can practice inhabiting these other ways of seeing the world and moving through it. He claims learning chess made him a more thoughtful and thorough analytic philosopher. Deception-based party games allowed him to bring a keener eye to faculty meetings where every professor was jockeying for funding.

If we can export the mindset a game encourages back to our real lives, how can we characterize the agency that The Witness inculcates? To borrow a phrase from another of the Einstein quotations in the game, it is the agency of the true searchers. Nguyen posits that games capture and encourage modes of agency through radical simplification—by removing other considerations and other possible actions, by providing a concrete goal, one is given the opportunity to act purely in a particular manner in a way not available amid the swirl of concerns of real life. The Witness, then, has effected a radical simplification of the search for true knowledge. One can partake of that “deep conviction in the rationality of the universe” that Kepler and Newton knew. Scientist or mystic, the player looks around the island and sees God’s hand at every turn.

The form of activity that Blow has shrunk and crystallized in The Witness is the form of thought at the core of all inquiry. It is slow, focused, faithful in its own ability to see more, given time. It is concerned with huge abstractions but grounded in rigor and specifics. The problems it presents require deep thinking but so often are solved by a flash of insight that sees across to a solution that was adjacent but orthogonal to the train of thought we were following. The real world is not a series of mazes on screens but its puzzles are solved the same way.

Doody says one other thing about labyrinths: “A labyrinth may take the place of pit or rocky tomb, and perhaps it always has some of the characteristics of those two other important topoi. But a labyrinth is always something more. In its intricacy is power, and to move rightly through that intricacy and out again is to assume that power.”

Great article! I absolutely adore this game. There are so few gaming experiences that make you feel so clever over and over again.

Ezra Klein did an interview a few years ago with Nguyen and they had an interesting discussion of Baba is You.

Would you believe, given my occupation, that I've never played this game? (Nor Braid, which is weird in its own way given that I was around for the indie boom...) It looks fun, as a very pretty delivery mechanism for pencil puzzles. Still gotta beat Baba is You first, tho.