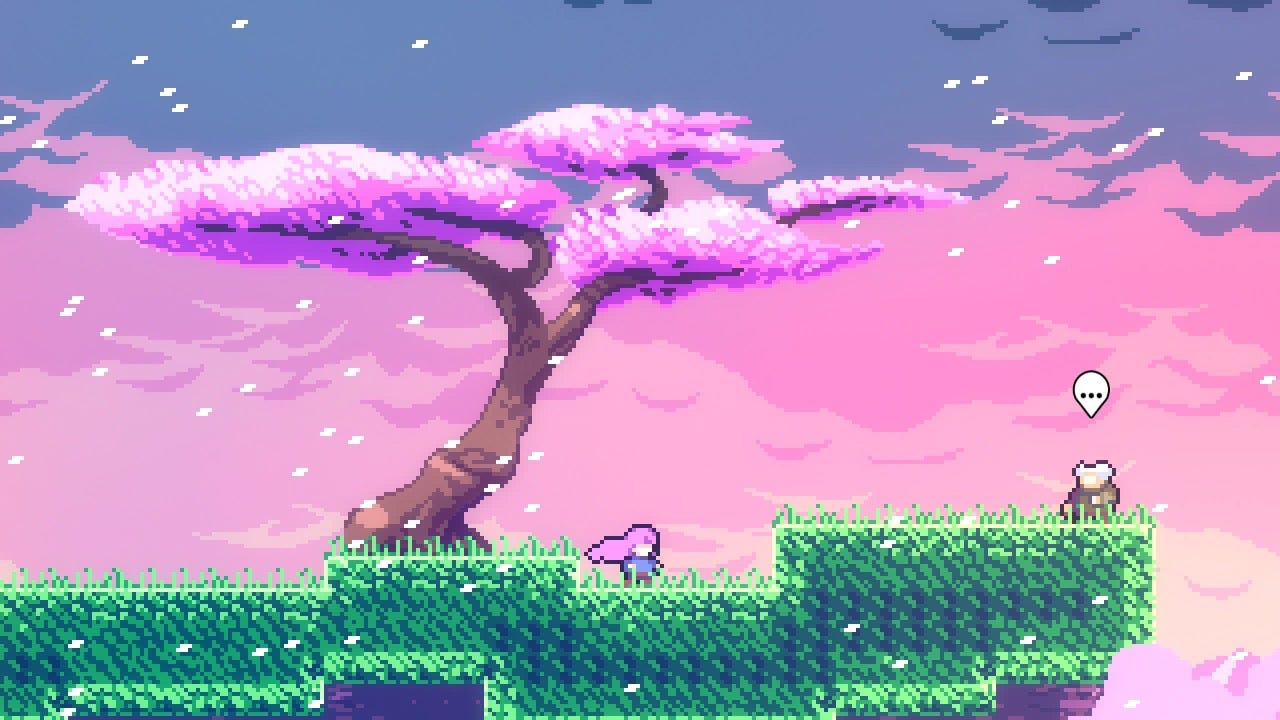

Sometime back in the spring, I started playing Celeste again. Fans will tell you, as a bit of joking understatement, that Celeste is a game about climbing a mountain. That doesn’t quite capture it. Celeste is a 2-D precision platformer—think Super Mario but ten times as sadistic. There are no power-ups, no advantages. Madeline has three moves: jump, wall-grab, and dash. The game presents this basic toolset and challenges you to master it perfectly. As Madeline, a young woman struggling with anxiety and identity issues, the player climbs Celeste Mountain, a mystical site whose energies force her to confront her problems and make the climb as much an internal journey as it is external. The second level, Old Site, is a dream; in it Madeline’s reflection escapes from a mirror and chases her, embodying all her self-loathing and self-sabotage. In later levels that take place in waking life, “Badeline” continues to harass her, having become very much real.

The most immediately apparent thing about playing Celeste is that you will die. A lot. If you fall, you die. If you touch a spike, you die. If you get squished, you die. Each level is broken into bite-sized “screens,” initially literally the size of the screen, the whole room visible at once, but they get progressively longer. Dying resets you to the beginning of the current screen so you lose minimal progress each time but completing a room for the first time might take dozens of tries. One of the only pieces of advice the game gives players is to “Be proud of your death count! The more you die, the more you’re learning. Keep going!” On my main file, where I’ve accomplished everything the game has to offer, my death count is more than 30,000.

This was the third time I made the climb. My first experience with Celeste was right after I got my Switch in 2019. It took me eight months to beat “Core,” the eighth and then-final level. Each level has what’s called a B-Side (unlocked by finding a hidden cassette, get it?), a variant that takes the mechanics of each level—Dream Blocks for Chapter 2, bouncy clouds for Chapter 4, etc—and ratchets up the difficulty significantly. Say goodbye to the floor—jumping and dashing between platforms hanging over the void is now the rule rather than the exception. I beat the first couple B-Sides before I decided that I’d reached the limit of my skill and tapped out.

About a year later I returned to the game and made some moderate improvements to my play. I learned a couple advanced techniques like wallbouncing and hyperdashing. It turns out, you see, that Madeline’s basic movement toolset can be combined in novel ways that the game either never teaches you directly or only does so very late. Wallbouncing, for instance, is done by dashing up parallel with the side of a wall and jumping before the dash ends, causing Madeline to propel herself off the wall for a big boost up and over, like so:

Hyperdashing is done by dashing diagonally down into the ground and jumping, shooting Madeline forward with a low launch angle, making it perfect for traversing a long gap between tight obstacles, like so:

I cleared all the B-Sides and unlocked the C-Sides, short 3-room gauntlets that push each mechanic to its limit and require perfect movement as well as advanced techniques like wall-bounces and hypers. I beat 1-C before tapping out, again convinced that I’d reached the limit of my skill.

When I quit my job last October and moved to Santa Fe, it was as if a huge weight had been lifted from my mind. Despite a pretty low actual workload, it constricted me and dominated my thoughts, basically exactly as David Graeber described in Bullshit Jobs. Lifting that weight led to a winter and spring that was particularly thoughtful and productive. But by, say, May, I was spiraling. My time, rather than a precious, newly recovered resource, had stretched and flattened into an endless plain that I was so anxious to fill that I couldn’t use it well. I had a research assistant gig I had to quit because I simply could not sit and apply myself to a task.

So when I returned to Celeste, it was time to go sicko mode. I read the wiki and learned about a staggering array of advanced tech beyond wallbounces and hypers—like neutral jumping, ultradashing, and corner kicks—that I’d never heard of. I learned the game has a robust modding scene and giant collaborative map packs that dwarf the base game. I still remembered how to wallbounce and hyper and I was amazed how much my abilities had not atrophied in the intervening years.

As if anticipating that only the deeply troubled and deeply obsessed would still be playing so many years later, I also discovered a new level, “Farewell,” a final challenge that shames the difficulty of anything that came before. Added a couple years after initial release by creator Maddy Thorson and her team, Farewell is so hard that it was initially planned to be gated off until players had beaten all the C-Sides; this requirement was dropped and replaced with a gate halfway through requiring only the completion of all the B-Sides. It’s at this point where Farewell’s difficulty jumps from around B-Side to beyond C-Side level and becomes so technique-demanding that the game essentially pauses to teach you how to wavedash. Wavedashing is the holy grail of Celeste techniques: a modified hyperdash in which the player starts their down-diagonal dash in the air, and then delays their jump button-press infinitesimally so that they get a strong hyperdash while refreshing their dash, allowing them to do another one in midair and cross ever vaster distances of empty space.

To make a long story short, I conquered all the C-Sides and concurrently worked through Farewell one section at a time. When I reached the point where wavedashes became required, I found a nice long flat spot at the beginning of Chapter 3 and spent hours practicing, back and forth, back and forth, until the technique was ingrained in my muscle memory and the slight jump delay felt natural. I spent probably around five hours trying to put together this sixteen seconds of gameplay to clear this one room.

It looks like nothing in particular but that’s quite possibly the hardest thing I’ve ever done in a game and I’ve beaten Malenia in Elden Ring.

I tell you this at such length because I want to demonstrate how tightly Celeste’s narrative themes are woven with its gameplay. Celeste is a game about a girl who doesn’t believe she’s up to the challenge she’s set but finds that her abilities exceed her own belief in herself. The game’s difficulty replicates this feeling for the player as it repeatedly convinces them that some challenge is beyond them, only to find that with enough persistence it can be surmounted. It’s a nice feeling. I’ve invested more than 100 hours in the game because it really is gratifying to look at a room and think, in Madeline’s words, “I can’t do this,” and then, after practice and repeated failure, to find that in fact I could do it. It’s a nice feeling, even if I can only find it in a video game.

I’m feeling terribly discouraged these days. More and more I’m convinced that my dreams of a proper writing career are worse than doomed and that everything I do with this newsletter is pointless.

The Underline was born from a simple realization: if I ever wanted to land a job writing about things I find meaningful, I needed a portfolio of work showing I could actually do it. And since I’m catastrophically bad at pitching, the only way I was going to create that portfolio was to do it myself. I never expected this newsletter to be make money or be the career itself. Two and a half years ago, the media landscape was in pretty bad shape but it still felt plausible there could be a job for me somewhere (or maybe I was just deluding myself even then).

Today I’m under no such delusions. The New Yorker is asking if the media industry is prepared for “an extinction-level event.” More than 8,000 journalism jobs were cut last year, according to the Press Gazette; around 1,000 more were eliminated in January 2024 alone. When I applied for a staff job at Defector in the spring I was elated to make it past the first round of weeding and let myself start dreaming about actually getting it. When I was rejected, beyond disappointment my reaction was mostly a matter-of-fact well that’s that—that was the last job left in this blighted industry and I didn’t get it. I have the portfolio now but there’s no one left to show it to and nowhere to go.

Well why not the newsletter then? There are a few reasons, first of which is that I’m a nobody. With few exceptions, every person who’s making real money on Substack is someone who already had a following either as an actual famous person or at least a big online audience from Twitter or whatever. I’m neither of those things. I’ve found it basically impossible to grow my audience. To be perfectly transparent with you, this newsletter has 130 free subscribers (I cherish every one of you). It has 5 paid subscribers, all of whom are IRL friends or family. Two years ago when I would post my articles on social media I could get some modest engagement; since then all the platforms have adjusted their algorithms to suppress any posts with links that will take users away to another website. Facebook swallows my posts into the void. I genuinely have no idea how to reach new readers.

I like to blame those factors outside my control, but more than anything I’m increasingly convinced I just don’t have the juice. When I read some of the other books writers I admire here—Phil Christman, Lyta Gold, BD McClay, Naomi Kanakia, Lincoln Michel—I am struck with undeniable force by how little I have to offer in comparison. Not only are they so much better read than I am, not only is their writing funnier, more elegant and effortless than mine, but they have something to say. I thought I knew how to write about books because I spent four years talking about a lot of very old ones, but reading those writers I realize I have no framework by which to relate books and zero vocabulary for how to describe prose. I feel exceedingly dim and dull these days. I have little insight to offer.

The evidence bears me out. When those writers post something, a lot of people click the little heart. Their readers comment. Their work generates a response from readers, because it’s good. My posts don’t get that reception. It’s a big day if a post gets two faves. No one comments. My whole FromSoft/Golden Bough series—9000 words I’m very proud of—came and went without any acknowledgement (except from the three people who unsubscribed). It’s hard to escape the feeling that literally no one gives a shit, that no one would notice or care if I never wrote anything again.

Early in Celeste, Madeline argues with Granny, an old woman who lives on the mountain. She tells Madeline to go home, that she’s not in the right frame of mind to make the climb, to which Madeline responds that she’ll make it to the summit just to stick it her. Granny relents but tells her to watch herself because “It can be hard to tell the difference between stubbornness and determination.”

Am I determined or am I just stubborn? Unfortunately it’s probably the latter. I’ve always been more of a dreamer than a doer. I think of myself as a writer, as someone devoted to the craft, but am I, really? If I were, wouldn’t I hold myself to a schedule, wouldn’t I read more, wouldn’t I have more than one or two posts a month? Wouldn’t that novel idea be more than an outline on a legal pad that I’ve told no one, not even Liz, about? I’m not cut out for it. But at the same time, I can’t give up the feeling that I deserve some modicum of success. When, on those rare occasions I manage to get out of my own way, I think I can produce something that’s pretty good. One Defector commenter said my Dune article was a contender for blog of the year—I’ve been living off that for six months. I can list reason after reason, both structural and personal, that my career is DOA but some stubborn part of me insists that I should be able to will it back to life.

And anyway, what the fuck am I going to do instead? I have no marketable skills. Writing little essays and book reports and mean things about Frasier is the only thing I know how to do. I truly could not get a job interview if my life depended on it. As long as I’m unemployed I might as well keep the posts coming even if they suck and no one reads them, right?

The dedicated Celeste player who clears 7-C finds Granny on the mountaintop at the end. “Funny how we get attached to the struggle,” she muses. I wonder if, when I dedicated myself to mastering Celeste this spring, I wasn’t substituting one struggle for another. I don’t want to give up on writing—I am attached to the struggle. But I have a son to raise and a wife who deserves for me to contribute financially. I didn’t want to think about what needs to come next. So I climbed a mountain.

2AM 4/26/25 currently struggling with and doing a writing-based assignment for a class, and remembered a quote that would shape a large theme for my story- "funny how we get attached to the struggle" and stumbled across this article. Love the analysis of the game, especially how the gameplay mirrors madeleines mental struggle. The parts connecting it to the writing experience feel so real. Im a high school junior who has no idea what to do in college or beyond that despite my good grades, mainly because everything im interested in is basically guaranteed 0 pay and unemployment. i wanted to be a writer of some sorts for a bit but i read the book "the death of the artist" by william deresiewicz for the same class im doing this writing assignment for (we were told to pick an issue-based nonfiction book), and i was basically like "damn, i guess i dont wanna be a writer anymore." can feel so much of the struggle described for writers and artists in that book here. But i also see the beautiful writers mind connecting and deeply evaluating ideas across multiple levels of reality that first pulled me into writing and the english language. Just want to say that this article has been great and thought provoking, and that celeste is a beautiful game that tells all of us to keep going in whatever struggle we have.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=keIWG6hSD7Q (similar idea i think)

I have a lot of thoughts about this subject haha.

One is—you are good at what you write about, imho, but this is a particularly awful time to be a writer without a lot of bylines, because almost all the entry-level publications are dead now. The feeling you are feeling is shared by basically everybody right now who doesn't have a good staff job, and those people live in fear of getting fired.

In that sense, it's actually not a bad idea to think about a job that would just let you write what you want, because there's a lot of freedom in just not being dependent on the ecosystem right now. It could be a job in a totally different direction, like being a mortician or whatever. I'm going through the same thing. Because…

Two—this feeling doesn't get better, ever, I think. There are paragraphs from this that could have come straight from my one am monologues and then I find myself in here as somebody who seems to be doing OK, etc. It's just kind of a lonely and difficult way to live. As long as the work itself is life-giving in some way, you should keep doing it, even if it's something you do in the mornings before you go off to your wage paying job and even if you feel like everything's going into a void. You're right that you have some objective numbers to look at here but you're wrong that if they were bigger you'd feel better about it (imho).

Three—you are really good at writing about video games (see: this post), and many, many people are not good at writing about video games. I don't know if that's what you want to be good at per se—something I've found about myself is that sometimes it's hard to respect your actual talents—but you should value that about your work.