A common thread across many of my favorite books, movies, and tv shows is the presence of a central character who can move between social spheres. This character often performs important plot functions through their ability to flout convention and bring together characters who otherwise wouldn’t interact, with the side effect that, to make these abilities believable, these figures are often the most charming or dynamic characters in their stories.

I locate the origin of this archetype in Falstaff, the corpulent knight who carouses with Prince Hal in Henry IV. I briefly considered Odysseus but first of all I just wrote about him and also his way of adapting himself to whatever situation he’s in is not quite the same as the expansive personality that accommodates all types I’m thinking of here.

Once you get to thinking about it the Falstaffian type can encompass many many characters but I’ll limit myself to four today. So, without further ado, here are some of my perennial and recent favorite Falstaffs (Falstaves?).

Sir John Falstaff (Henry IV, Parts 1&2)1

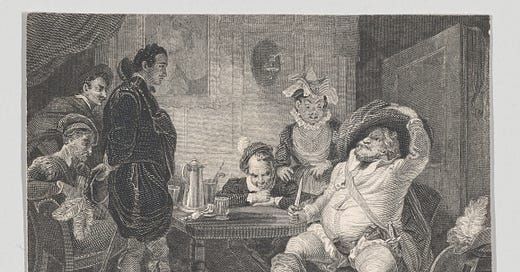

We simply have to start with Falstaff himself. He originates the type but it’s a type that lives through each character’s specific personality. Along with Lear’s Fool and Rosalind from As You Like It, Falstaff is one of those Shakespeare characters whose every line of dialogue jumps off the page with life and liveliness. He’s the comic relief of his plays but he is far more than that.

Falstaff, as his title implies, was once a respected knight who now finds himself down amongst the rabble. He blames it on Prince Hal, who appears to all the world to be an irredeemable screw-up incapable of rousing himself to anything nobler than drinking and womanizing. Falstaff claims that Hal pulled him down into the gutter as part of Hal’s plan to “imitate the sun, / who doth permit the base contagious clouds / to smother up his beauty from the world, / that, when he please again to be himself, / being wanted, he may be more wondered at / by breaking through the foul and ugly mists / of vapors that did seem to strangle him,” but it’s always been my sense that Falstaff is far more comfortable with the lowlifes of the Boar’s Head Inn than Hal is.

How Falstaff came to live among thieves on borrowed funds is unclear but it’s clear enough that Hal has used him as an example while always holding himself slightly apart. This is made apparent early in Part 1 when Hal decides it would be more amusing to double-cross Falstaff and company during their little highway robbery escapade; rather than feeling solidarity with his fellow thieves Hal treats it as a game to win. Falstaff, fully united with his drinking buddies, gets played for the dupe.

Falstaff is a man of pleasure. He’s rotund (Shakespeare was not above a fat joke). He’s a drunk. He’s horny. These are great qualities! If he’s a slave to his passions, well, aren’t we all? This capacity for enjoyment gives him so much life. It shows us what Hal sees in him, what he sees in this life outside the royal court that could be so beguiling.

Despite his fallen material conditions, Falstaff maintains a certain level of status among the elite. When Northumberland and Hotspur’s rebellion breaks out into war, Hal calls up Falstaff as a general and grants him conscription powers. I can’t say he rises to the occasion exactly—he uses those powers as a moneymaking opportunity, fields such a raggedy division that even Hal comments on it who are immediately massacred, and proves a coward on the battlefield—but that’s just it: no one thinks the less of him! His esteem is not lowered in the slightest! Falstaff is so charming, is so perfectly himself, that the nobility simply accept it. Somewhere in Henry’s court he has a hater doing the Jesse Pinkman meme:

Hal compares himself to the sun, which can be obscured but remains unchanging. Falstaff, it’s worth noting, considers himself one with the moon:

"Marry, then, sweet wag, when thou art king, let not us that are squires of the night’s body be call’d thieves of the day’s beauty. Let us be Diana’s foresters, gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon, govern’d, as the sea is, by our noble and chaste mistress the moon, under whose countenance we steal."

Falstaff embraces his changeability. He identifies with the celestial body that represents eternal change, waxing and waning, raising and lowering the tides, just as his fortunes rise and fall. He’s most comfortable in flux. It’s this quality that ultimately forces Prince Hal to repudiate him when he takes the throne. As we see with his father, kingship turns a man into a statue. Henry Bullingbrook is a charismatic, exciting character in Richard II; when we meet him again as Henry IV he’s stiff and oratorical. When Hal becomes Henry V his internal contradictions must be stamped down and hidden out of sight. Falstaff is too much a reminder and embodiment of the rich, incompatible possibilities of life. He has to go.

Octave (The Rules of the Game)

The Rules of the Game, directed by Jean Renoir and released in 1939, is my single favorite film. It concerns a group of French aristocrats who are all having affairs with each other and gather at a country estate for a week of hunting and revelry. At the head of the table are Robert, Marquis de la Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio) and his wife Christine (Nora Gregor). La Chesnaye is having an affair with the glamorous Geneviève de Marras (Mila Parély) that predates the marriage; Christine is somewhat involved with André Jurieux (Roland Toutain), a famous aviator. Also in their social circle is Octave, a failed conductor who has known Christine since childhood, played by director Jean Renoir. This makes Octave another important character type, the director self-insert, which has its own tradition going back to Aristophanes in The Clouds, but that’s a topic for another day.

The film spends its first twenty minutes introducing us to all these characters and establishing the web of relationships in Paris before the action moves to the chateau. Octave flits through all these early scenes, talking to each of our other main characters and saying just the right things to make sure everyone gets an invitation to the festivities. It’s very easy to miss on first viewing but Octave is very much the author of everything that ensues.

Once they head to the country he recedes for a quite a while as the plot turns to the romantic entanglements of the aristocrats. We also spend time with the servants, who include Christine’s maid Lisette (the incredibly charming Paulette Dubost) (whom Octave is said to have a relationship with), her husband the severe and trigger-happy groundskeeper Schumacher (Gaston Modot), and Marceau (Julien Carette), a rabbit poacher and natural enemy of Schumacher who immediately begins flirting with Lisette.

During the great masquerade that follows the hunt, Octave dresses up as a bear. This stands out—no one else has made themselves an animal. Once his group’s little performance is over he begs his friends to help him get his costume off but they’re all too consumed with their romantic politics to spare a moment. He’s in despair. This is the dark side of being the Falstaff figure: he’s the social equivalent of “jack of all trades, master of none”—everyone loves Octave but he’s not their priority.

Late in the film, Octave’s bravado fails him. He sits on the steps outside the party with Christine and talks about his failed career and his stifled ambitions. His place in this social circle suddenly seems a lot more precarious. La Chesnaye and the others are to the manor born. Octave is an artist, which grants a certain amount of social capital, but he’s a failure. Other characters ask him unprompted if he needs money.

Without Falstaff, Henry IV would be a one-note tale of nobles squabbling. Likewise, it’s Octave’s vulnerability that cracks open The Rules of the Game and makes it so much more than an upstairs-downstairs bedroom farce. His deep melancholy is real for us in a way that, say, André Jurieux’s spurned lover act never will be. He exits the film ambiguously, last speaking to Marceau the poacher and wishing him good luck. It seems in that moment he feels more kinship with him than any of the rich folk he’s known for years.

Like Falstaff’s invocation of the moon, Octave’s very name speaks to a certain dualism or uncertainty. The octave is the high and the low at once—the same note, but not the same note. Is it the one or the eight? It’s all a matter of perspective.

Major Misato Katsuragi (Neon Genesis Evangelion)

In the case of Falstaff and Octave, the different social worlds they move between are a matter of class, status, and nobility. In the case of Evangelion, we’re dealing with the boundary between the world of the adult characters and that of the children.2 For my readers who have not spent the last year obsessed with an anime from 1994, Evangelion is the postmodern mecha anime, in which teens with depression pilot giant robots to fight alien beings on behalf of NERV, a shadowy agency with an agenda far different from protecting the earth. Our protagonist is Shinji Ikari, the fourteen-year-old son of the commander of NERV, Gendo Ikari, who wants nothing less than to pilot the Eva. His fellow pilots are Rei Ayanami, a girl with no past, and Asuka Langley-Soryu, a flirt who lives to impress with her skills as the world’s greatest pilot.

Since Shinji’s relationship with father is, uh, fraught, he lives with Misato, the charming, funny, and beautiful Head of Operations at NERV. Once Asuka arrives in episode eight, she moves in with them as well to form a strange, quasi-incestous family unit. Misato is the only link between the adults and the kids. Gendo wants nothing to do with Shinji or Asuka (Rei is another matter). Asuka’s supposed guardian, Ryoji Kaji, is a double agent with his own agenda who quickly distances himself. NERV’s head science officer, Dr. Ritsuko Akagi, is not exactly the motherly type.

That leaves Misato, who does genuinely care for Shinji and Asuka’s wellbeing and who is literally doing her job in keeping these children willing to plug into a robot and face death on a regular basis. Misato is highly socially adept and frequently affects a ditzy persona to mask the steely resolve that undergirds her personality. No moment better exemplifies this dynamic than episode 12, “A Miracle’s Worth,” in which the pilots have to stop an Angel that plans to drop from orbit onto NERV HQ to obliterate it. Misato tasks them with literally catching it as it falls, a plan with a probable success rate well below 1%. When she looks at them afterward she does this little smile that’s unlike any expression we see her make elsewhere in the series. She loves these kids and she truly thought she was sending them to their deaths.

It can’t be overstated how much Misato is the character you will fall in love with on first watch of Evangelion. She is so funny, she has legs for days, her fridge has nothing in it but beer. Beyond that though, she is the character most capable of action. Evangelion is fascinating because almost every character in it is completely denied agency of any kind. The children are under the thumb of NERV and are only capable of acting in the world by piloting the Evas or in their personal romantic lives. The other adults do their jobs and are either in the dark about NERV’s true intentions or are complicit in them. Atop it all sits Gendo, whose “scenario” is inescapable.

Then there’s Kaji, Misato’s ex, a suave operator who hides his own intentions behind three or four levels of dissimulation. He ends up turning his back on both Gendo and his other masters as his allegiance shifts to Misato and to the truth. Kaji is capable of poking his nose where it doesn’t belong and getting to the bottom of things but there’s a sense in which even he can’t really do anything with his findings. Misato can. In the way that Falstaff brings people together and shows them a way to be, when Misato goes looking for the truth she brings along Shinji and Ritsuko and changes their perspectives. She possesses that Falstaffian something that frees her from self-imposed expectations of conduct to follow her conscience and pull other characters into her orbit.

And the way she drinks is truly iconic:

Steerpike (Titus Groan)

Like Misato, Steerpike is the only character capable of action in an otherwise frozen world. One of my favorite reads last year, Titus Groan takes place within Castle Gormenghast, a vast crumbling estate governed by rituals and practices whose origins have been lost to the mists of time. The other characters act out their roles and pass their days in an elaborate mummer’s farce. This is, to characters like the Earl’s servant Mr. Flay and loremaster Sourdust, exactly as it should be. Steerpike is the wrench in the gears that disrupts the castle’s sleepy, orderly functioning and ushers in the future.

Steerpike is a climber, literally. At the novel’s outset he’s a lowly kitchen boy who desires nothing more than escape. During the disruptions and revelry prompted by the birth of Titus, Steerpike steals away, only to be caught by Flay, who lets him catch a glimpse of the Earl’s daughter Fuchsia before locking him in a drawing room. Steerpike knows that if he waits for Flay to return he’ll simply be returned to the hell of the kitchens. Instead, he climbs. He opens a window and takes his life in his hands to scale the outer wall to the roof. Falling would be death. He’s lost on the roof for days searching for a way back into the castle elsewhere. He sees things up there not seen for generations. Near death, he climbs a great vine ever higher and makes his way into Fuchsia’s tower, violating her special, secret hideaway.

In climbing, Steerpike sets himself free. When Flay left him in that room, he was under his power. When he returns, Flay can no longer touch him. Steerpike maintains a fiction that he is now in the employ of Dr. Prunesquallor but he’s hardly fooling anyone. From Prunesquallor he quickly moves on to the twins, Cora and Clarice, Lord Sepulchrave’s sisters who harbor an unappeasable resentment that they have been pushed aside in the castle’s hierarchy. A strange pair seemingly of one mind split between two bodies, Steerpike sees in them pliable tools that will allow him to rise to the highest levels of power in Gormenghast.

Steerpike makes for a sort of inverted Falstaff. Where Falstaff follows his passions, Steerpike is utterly bloodless. “Steerpike had an unusual gift. It was to understand a subject without appreciating it. He was almost entirely cerebral in his approach. But this could not easily be perceived; so shrewdly, so surely he seemed to enter into the heart of whatever he wished, in his words or his deeds, to mimic.” Steerpike demonstrates the difference between being and seeming. Falstaff is a remarkable figure because he’s at home wherever he goes. He is capable of being, without any falsity, both high and low, comfortable in the royal court or the Boar’s Head Inn. Steerpike is masterfully able to take in a scene and affect a persona that will be accepted, even applauded. But it is false. It is pure calculation. Beneath the mask there is no enjoyment or discomfort, merely expediency.

Not only is Steerpike a mirror-version Falstaff, Fuchsia makes for a Prince Hal stand-in. Fuchsia resents her position as the Earl’s daughter, resents how she has been kept “upstairs” her entire life. She has an imagination and creative spirit that yearns for expression but it’s been smothered in the attic. She dreams of leaving the castle, of consorting with the servants and shedding her noble status that has only constrained her. She’s fascinated by Steerpike because he shows her it’s possible to live without those constraints. She is drawn to him powerfully but always holds back. By the end of the story, after her father goes mad (a result of Steerpike’s elaborate schemes), she accepts her place in Gormenghast and puts aside her thoughts of escape. She thus ends up at the same place as Hal when he’s crowned king, but without ever having lived the way he did.

Yeah yeah and Merry Wives of Windsor, leave me alone

or Children, as it were

Fantasmo! Especially 3 and 4 (I also read Titus Groan for the first time last year).

I was not prepared for number three.