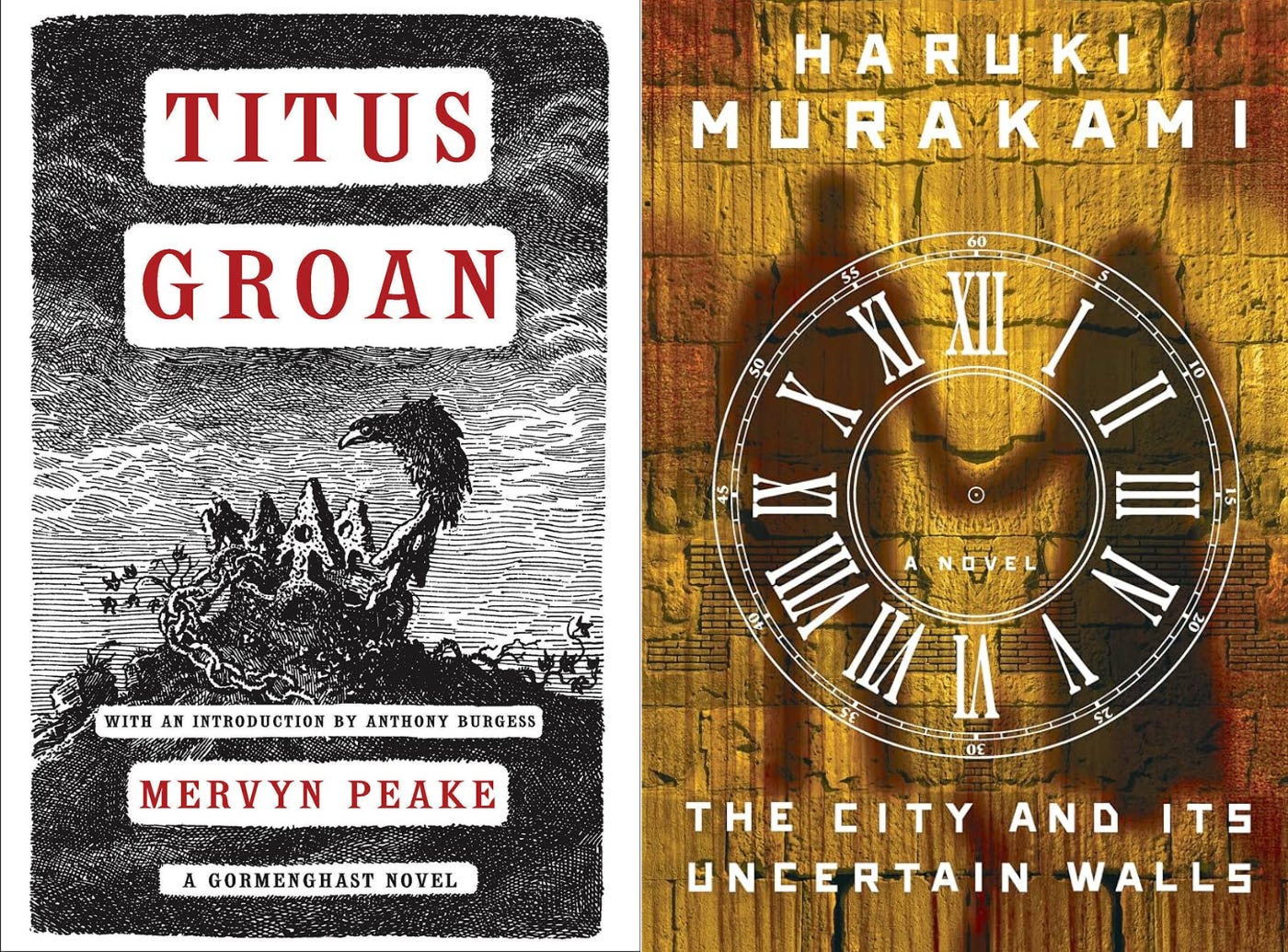

Hey gang, welcome to another book report. Doing these as a monthly thing has started to feel too rigid to me lately so we’ll be doing them on a rolling basis going forward. In this edition we have Haruki Murakami’s latest as well as Titus Groan, a Gothic classic from the 40s which I only discovered recently. A quick reminder that the links on the titles are my affiliate links so please use those if you want to buy any of these books so I make a couple bucks. Thanks!

Titus Groan, Mervyn Peake, 1946

The first scene of Titus Groan shows us in miniature the book as a whole. High in the attics of crumbling castle Gormenghast slumbers The Hall of Bright Carvings. Each year the carvers who live in the mud dwellings outside the walls of Gormenghast are invited in to present the wooden sculptures they have spent the previous twelve months carving. Those carvings deemed worthy are brought to the Hall, where they are cared for by Rottcodd, one of the castle’s ancient denizens who never leaves the Carvings and can go years without seeing another living person (his meals arrive by dumbwaiter). Dust lies thick in the Hall of Bright Carvings; each day Rottcodd dutifully dusts the Bright Carvings, kicking up great swirls of dust in so doing which will soon settle on the Carvings again. The carvings not selected for the Hall are burned.

Enter the grounds of Gormenghast and enter Mervyn Peake’s astounding vision of a sealed world of dead ritual and deformed humanity. Find scattered throughout the labyrinthine passageways Lord Sepulchrave, the seventy-sixth Earl of Groan, a melancholic whose days are consumed by the endless ceremonies his station demands even as their purpose is lost to living memory; his wife Gertrude, a rotund woman who cares only for her flocks of birds and great posse of snow-white cats; their daughter Fuchsia, a teenager possessed of a wild and artistic mind that has suffocated in her cramped and airless existence within the castle walls; Ladies Cora and Clarice, Sepulchrave’s twin sisters, so similar that even their thoughts align exactly; Mr. Flay and Mr. Swelter, servant to the Earl and the head chef, respectively, mortal enemies; and Steerpike, a cunning and deceitful kitchen boy who will stop at nothing to worm his way to the top of the castle’s hierarchy.

But today is no ordinary day, for Lady Gertrude has given birth to an heir, a baby boy named Titus. The castle is in uproar—His Diminutive Lordship, as Titus is called by Sourdust, the keeper of the Groan lore, will one day succeed his father and take up the mantle of seventy-seventh Earl of Groan and Lord of Gormenghast. For the first time in decades, change, or perhaps as yet merely the possibility of change, has entered the walls.

Titus Groan is amazing, a full-throated recommendation from me. Its plot is slow to reveal itself but absolutely gripping once it gets going. The characters are equally fully realized and inscrutable, ensconced as they are within epistemic and imaginative frameworks that we could never hope to penetrate. More than anything though it is a colossal achievement in sustained prose. The writing just goes so hard. Peake’s style is baroque yet skeletal—his sentences twist and turn but every adjective is a dagger slipped between the ribs. Here, have a taste, chosen essentially at random:

Drear ritual turned its wheel. The ferment of the heart, within these walls, was mocked by every length of sleeping shadow. The passions, no greater than candle flames, flickered in Time’s yawn, for Gormenghast, huge and adumbrate, out-crumbles all. The summer was heavy with a kind of soft grey-blue weight in the sky—yet not in the sky, for it was as though there were no sky, but only air, an impalpable grey-blue substance, drugged with the weight of its own heat and hue. The sun, however brilliantly the earth reflected it from stone or field or water, was never more than a rayless disc this summer—in the thick, hot air—a sick circle, unrefreshing and aloof…

Distance was everywhere—the sense of far-away—of detachment. What might have been touched with an outstretched arm was equally removed, withdrawn in the grey-blue polliniferous body of the air, while overhead the inhuman circle swam. Summer was on the roofs of Gormenghast. It lay inert, like a sick thing. Its limbs spread. It took the shape of what it smothered. The masonry sweated and was horribly silent. The chestnuts whitened with dust and hung their myriads of great hands with every wrist broken.

Goddamn I love it so much. There’s another section, earlier in the book, where Steerpike and Fuchsia are caught in a rainstorm while climbing the foothills of Gormenghast Mountain. It’s one of those perfect scenes where every detail—the rain picking up, the steepness of the slickening rocks, the description of the grotto they shelter in—feels freighted with metaphor and meaning. Reading it, I felt a flash of childhood, when reading was pure magic and every word was pregnant with possibility. I cannot wait to read the sequels.

The City and Its Uncertain Walls, Haruki Murakami, 2024

Haruki Murakami’s new novel, The City and Its Uncertain Walls, contains an afterword. In it, the author explains that the book has its origin in a novella he wrote in 1980, just after the publication of his first novel, Hear the Wind Sing. Though it was published in a Japanese literary magazine, Murakami was unsatisfied with the novella and has never allowed it to be republished. He continues:

Still, from the first I felt that this work contained something vital for me. At the time, though, unfortunately I lacked the skills as a writer to adequately convey what that something was. I’d just debuted as a novelist then and didn’t have a good idea of what I was capable, and incapable, of writing. I regretted publishing the story, but figured what was done was done. Someday, when the time was right, I thought, I’d take my time to rework it, but till then would keep it on the backburner.

He goes on to describe coming back to the story multiple times over the decades, expanding and revising, and characterizes other books of his as responses to this unknown project. Finally, in 2020 when the pandemic shut everything down, he returned to the story again to produce a final version, forty years after its initial conception.

The City and Its Uncertain Walls (out in English tomorrow) begins with its unnamed narrator recounting a relationship he had when he was 17. As he and his girlfriend, also left nameless, sit on a riverbank at dusk, she tells him that the body he has his arm around isn’t the real her. The real her is somewhere far away, sequestered in a town behind a high wall. Soon this town behind the wall becomes their chief topic of conversation, he writing down every detail she provides. Alternating with this relationship history, the narrator tells us that ultimately he found this town and entered it. To pass the Gatekeeper who guards the only passage through the high wall, the narrator had to give up his shadow and have his eyes mutilated to prepare him for his new job as Dream Reader at the town’s library. He does these things willingly, so intent is he on finding the girl’s true self, who works as his aide at the library. She doesn’t know him, however, having no knowledge of his past with that other girl he knew. The town is also home to a herd of unicorns.

As I understand it, that was the extent of the original novella. Here it constitutes only about the first quarter of the story. My familiarity with Murakami is far from complete and certainly this first section was reworked when he came back to the project, but it does feel like the work of a less mature artist than the Murakami I know. It’s intriguing, certainly, and disorienting when the narrator claims to have physically gone to a place created in the imagination, but there’s a hard to articulate so what to the proceedings. We have these various fantastic elements—the dream reading, and separable shadows, and the unicorns—but they remain mere oddities observed by our blank-slate narrator. They jump off the page as obvious signifiers of something but on closer inspection don’t contain much signification.

Eventually, through circumstances that even he doesn’t understand, he finds himself returned to his apartment in Tokyo. It’s at this point we learn that decades passed between his teenage relationship with the girl and his finding his way to the town surrounded by high walls. He’s in his forties, unmarried, with a job in book distribution. Though he’s dated a few women, he remains haunted by the girl of his youth. He’s unhappy that he’s returned to the real world and is consumed by “the visceral sense that this reality isn’t a reality for [him].” If he can’t be the Dream Reader in the library in that town, he must be a librarian in this world, preferably in some small, isolated community. Well, circumstances align and he soon moves to the small town of Z**, walled in by high mountains in the Fukushima province.

Thus begins Part II of the novel, which, while still strange and explicitly supernatural, is much more grounded and satisfying than Part I. Murakami’s gifts lie in the depiction of life lived, of how ideas and experiences grow through the routine and repetition of our daily lives. That skill is on full display throughout the rest of the book. The narrator settles into his job and slowly gets to know the previous library director, Mr. Koyasu, who offers him guidance. He starts going to a coffeeshop and over a series of scenes develops enough rapport with the owner to ask her on a date. The seasons change. The library cat has kittens. While the narrator’s life is quite repetitive, the book is not boring and watching him live out his routine is not tedious. The way his rote actions begin to accrue meaning over time is quite powerful.

One might wonder if the two sections fit together into a complete work. Ultimately I think they do. They are very different and reflect very different perspectives to take in the scope of Murakami’s artistic development. The youth dreams of escaping and making their fantasies real. The man knows that fulfillment must be found in this world, and knows it can be done.