Something I love doing lately is drink two beers and then browse the Switch eshop. Thanks to the release of the Switch 2—I assume—the deals there have been crazy. Everything is on sale—I’m talking markdowns of 75% or more; formerly $60 games for 5 bucks. The Metal Gear Solid Master Collection was only half off but, as it brings together two powerful tendencies of mine, I still couldn’t resist (and, again, the two beers). Those tendencies are 1) the impulse to go back to a medium’s earlier works to construct a canon and 2) the desire to apply cinema’s auteur theory to a form that has few recognized creative visionaries.

Metal Gear Solid checks both boxes. It was a pioneer in 3D stealth gameplay and is widely considered a foundational “text” of video games. And it can be attributed to the vision of its director and writer Hideo Kojima, whose idiosyncratic and maximalist approach to both game design and storytelling has made him one of the few household names of the industry. Further bolstering the auteur theory angle, Kojima cites numerous film influences and has spent his career pushing the limits of video game hardware to chase cinematic presentation in his games.

The other thing about Metal Gear Solid is it’s completely fucking bonkers. Are you ready for some Proper Nouns?

The player is Solid Snake, a grizzled spec-ops veteran unapologetically modeled on Kurt Russell’s character Snake Plissken from Escape from New York, who’s brought out of retirement for One Last Job. His mission: infiltrate Shadow Moses Island, off the coast of Alaska, a military testing facility that has been taken over by the members of his former unit FOXHOUND. They have seized Metal Gear Rex, a walking mech tank with nuclear launch capabilities. Their demands include one billion dollars and the remains of their dead leader Big Boss, on threat of using Metal Gear for a nuclear strike.

Okay, deep breath, pause. So here’s the thing. Metal Gear Solid is actually the third game in the series. It was preceded by two 8-bit games released in 1987 and 1990 for the MSX2 computer system (???) and ported to the NES. These games are included in the Master Collection but I just can’t with games of that era. The story of the original Metal Gear is Snake infiltrating the fortified breakaway rogue nation of Outer Heaven, which has a Metal Gear; at this point he’s a member of FOXHOUND under the command of Big Boss. Surprise! Big Boss is the man behind Outer Heaven—you’ve been taking advice from the bad guy! Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake is basically the same but set somewhere called Zanzibar; Snake kills Big Boss in that one. These games, despite being deeply inaccessible, especially in 1998 when MGS was released, are binding canon and Kojima references them freely, as if he expects everyone playing to be familiar.

So anyway, FOXHOUND wants Big Boss’s DNA and Snake needs to stop them from using their Metal Gear to initiate Armageddon. To do so he’ll have to sneak his way past enemy soldiers and cameras, acquiring weapons, equipment, and higher-level key cards as he goes. This is the template of basically all stealth games, but it’s important to remember that Kojima established the template and brought it into the third dimension for the first time with this game.

But he has sort of only half brought it into 3D. Despite the Playstation 1’s capacity to render 3D environments, Kojima has maintained the overhead perspective from the earlier 2D games. This is the biggest hurdle for a modern player. It’s a baffling and frustrating choice. I can’t tell you how many times I alerted a guard or a camera when I first started because you just can’t see more than ten feet in front of you. You’re in a big warehouse with soldiers on the far side of the room and you don’t know they’re there because you’re looking down at Snake from above. Now, you can press a button to go first-person mode to look around, but why do it that way? Why not a camera that follows Snake from behind? This seems obvious now.

But maybe it wasn’t obvious in 1998. It is easy to forget that Super Mario 64 had come out only two years prior in 1996. Metal Gear Solid’s development began before that in 1995, when there were only overhead views or first-person views a la the original Doom. The idea of a floating camera looking over the shoulder didn’t exist yet. The entire industry was trying to figure out what the transition to 3D would mean for game design. For all the ways MGS was pushing the boundaries of the art form, Kojima opted for a conservative, difference-splitting approach in his presentation. Or perhaps was it the inclusion of the radar? Did Kojima and his team think players would not be able to correlate the overhead view on the radar if the camera wasn’t also looking from that angle?

In River of Shadows, Rebecca Solnit’s incredible book about the perceptual changes in human consciousness wrought by the technological innovations of the 19th century—photography, telegraphy, and railroads, chiefly—she describes the elation and fear felt by early train riders in the 1830s. These trains could achieve maximum speeds of maybe 35 miles an hour but people worried they would be annihilated traveling what was to them so fast. One of these early demonstrations culminated in a man being struck by a train coming the other way when they stopped for a break. Solnit writes, “It is hard to imagine the reflexes and responses that made it impossible to step away from a noisy locomotive going perhaps thirty miles an hour, but Huskisson could not.” She goes on to elaborate on the way, prior to the industrial revolution, life was conducted at the pace of nature—people were limited by the speed and capabilities of bodies, theirs or their animals, be they horse or carrier pigeon. Clocks were rare before factory work.

Each event and thought itself must have been experienced at a radically different pace—what was slow then was slower than we could now tolerate, slower than we could pay attention to; while the speed of our own lives would have gone by them like the blur of speed before Muybridge’s images… Distance had a profundity that cannot be imagined now: a relative who had moved a hundred or a thousand miles away often seemed to have dropped over the horizon, never to be seen again, and travel for its own sake was rare. In some psychological and spiritual way, we became a different species operating at a different pace, as though tortoises became mayflies. We see much they did not, and can never see as they did.

Playing this video game from less than thirty years ago gives me a small sense of this sort of great change. It is hard to imagine that the relationship between a minimap and a ground-level view of the world could be confusing. But on the other hand I struggle to muster the patience this game asks for. The friction of having to stand still and hold a button just to look across a room is almost unbearable in an era of game design that seeks to eliminate friction above all. Players back then apparently enjoyed watching the guards walk back and forth, they liked hiding under their cardboard box and creeping forward three steps each time the camera swiveled away. They didn’t mind dying over and over and having to attempt the section again in a slow accumulation of knowledge. I am so impatient to get to whatever’s next that it’s very hard to appreciate what is happening in the moment.

I was reminded of Brian Moriarty’s comments in his GDC lecture The Secret of Psalm 46 that the vocabulary of video games largely hasn’t been invented yet, that there’s a whole dictionary waiting to be coined. Playing Metal Gear Solid I found myself thinking that we specifically need better language to talk about classic games. Like no other artistic medium (or at least not to the same degree), video games are a product of their era and its technological limitations. Coming just at the advent of the leap to 3D, Metal Gear Solid is doing so many new things, is pushing its medium to places it had never gone before. But you have to strain to see those innovations because they have become so fundamental to the design of any game that involves moving a character through a 3D world as to become invisible. It’s like looking at Brunelleschi’s first paintings to employ perspective realistically—it’s just about impossible to appreciate the newness on display when it has become axiomatic.

Or, on the other hand, Kojima is trying things that quickly slipped into hack gimmickry. The Psycho Mantis fight is legendary for the fourth-wall breaking. In the cutscene before the boss fight, Mantis, the telepath, reads the player’s memory card and reacts to what he finds there. If you have save data from Castlevania: Symphony of the Night he looks straight out of the tv and says he sees you’re a fan of Castlevania. During the fight he reads your controller inputs and dodges your attacks until you take your controller out of port 1 and switch over to port 2. Idk, I guess this hit different in 1998. I was not impressed.

A difficulty here is the technical aspects of the code behind the innovations. When I move Snake under those infrared beams in the clip above, I feel something of the epochal step forward its gameplay constituted. The precision of movement, the fluid transitions between poses, it’s really something. But I struggle with what to say about it beyond that it’s impressive. Maybe the thing to remark on is the fact that animation and hitbox work that precise can exist side by side with the sloppy and frustrating top-down gunplay that feels impossibly outdated. Metal Gear Solid shows us a form undergoing a radical transformation. The rules were not set in stone. Even as it had one foot in the future, the other was planted firmly in the past.

Sorry, I got off track. Let’s get back to the story, because it’s so bananas. The genius and stupidity of Metal Gear Solid is simple: Kojima has taken a standard 90s political or military thriller and run it through an overheated anime filter. It’s a familiar “loose nukes” setup that was everywhere in the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, but rather than our hero being a Jack Ryan CIA analyst and our villains some IRA splinter cell we have the comically jaded Solid Snake up against the FOXHOUND menagerie, which includes the gunslinger Revolver Ocelot; hulking Inuit shaman armed with a F16 minigun Vulcan Raven; seductive hunter Sniper Wolf; and Psycho Mantis, born possessing telepathy and telekinesis. Leading FOXHOUND is Solid Snake’s twin brother Liquid Snake, who seeks to follow in Big Boss’s footsteps.

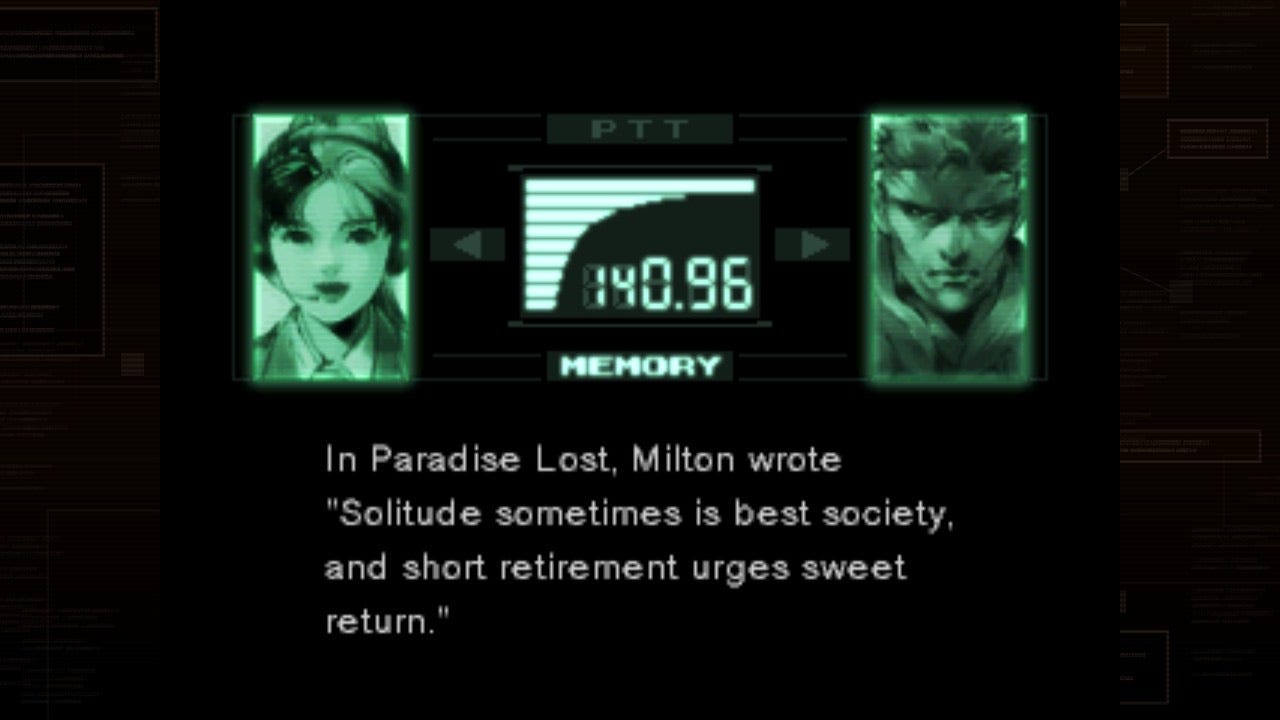

On our hero’s side, we have another full cast. There is so much dialogue in this game, all of it voice-acted. Snake frequently checks in with his team via earpiece. They include his commanding officer Colonel Campbell, who suffers a slow humiliation over the course of the game as it’s revealed he has withheld piece after piece of vital information from Snake and is forced to apologize sheepishly time after time. Dr. Naomi Hunter is the medical expert; in the game’s final act there are so many revelations of betrayal and misdirects and conflicting accounts regarding Naomi I honestly am not sure of what she did and didn’t do. Meryl Silverburgh is Campbell’s niece, an inexperienced solider who was stationed on Shadow Moses Island; Snake’s relationship with her is as close to something we could call the “emotional core” of the story. Snake also rescues Hal “Otacon” Emmerich, the chief designer of Metal Gear Rex, who didn’t know it was meant to launch nuclear warheads and got into his line of work because he loves mecha anime.

There’s also a cyborg ninja running around who turns out to be Grey Fox, a comrade Snake thought died in Zanzibar in MG2 but who was actually used as a cybernetic test subject; he also turns out to be Naomi’s adoptive brother and guardian, and her anger at Snake for his “death” is what fueled her motivations for revenge that caused her to infect him with the FOXDIE virus. The FOXDIE virus is a special virus that only targets people with DNA sequences it’s been programmed to recognize. There’s so much DNA talk in this game, which is also very 90s. Naomi talks at length about how she went into DNA research because she didn’t know her parents or her origins and thought learning about her DNA would help her know her self and where she came from. She basically invented 23andMe, is what I’m saying.

Whew, where was I? It’s amazing how Metal Gear Solid’s plot is so simple—Snake rescue hostages, Snake shut down Metal Gear—and so gonzo that it’s nearly impossible to talk about in a coherent, linear way. Its plot and its dialogue are jam-packed with stuff. This isn’t a game with ideas, really—its analysis doesn’t extend farther than “loose nukes bad, our DNA not dictate our destiny”—but it certainly has a lot of things on its mind. Kojima’s willingness to throw it all in the mix and write it all out in such an operatically expository manner pushes the game into the realm of the ridiculous sublime. I mean, please just watch Liquid Snake’s great speech atop the wreckage of Metal Gear Rex from the climax of the story:

Liz watched this cutscene with me after having seen basically none of the game preceding it. We were hooting and hollering. Like every line of Liquid’s is a villain speech cliche turned up to 11. “But things... are different now. With all the liars and hypocrites running the world, war isn't what it used to be... We're losing our place in a world that no longer needs us. A world that now spurns our very existence. You should know that as well as I do. After I launch this weapon and get our billion dollars, we'll be able to bring chaos and honor... back to this world gone soft. Conflict will breed conflict, new hatreds will arise!” “We were accomplices in murder before the day we were even born.” And all of this uber-dramatic speechifying from characters so low-poly they barely have faces. God it’s so good.

Also, Liquid says that he and Snake split Big Boss’s DNA, with Snake getting all the good stuff and Liquid getting the junk. This is literally the plot of the Arnold Schwarzenegger/Danny DeVito movie Twins?????

But for me the iconic, defining scene of Metal Gear Solid’s aesthetic and emotional register is when Snake and Otacon talk at length about using an elevator and then Otacon, who has inexplicably fallen in love with Sniper Wolf even though she shot Meryl and took her hostage, asks Snake if he thinks “love can bloom even on a battlefield.”

Does it get better than this?? Nothing has made me feel like I’m thirteen again like this game in years and years. This is peak faux-profundity and I love it so much. Want one more? Here’s Vulcan Raven’s death scene, which culminates in him being skeletonized by his flock of ravens:

I recently learned from this article a fun Joan Didion quote which goes, “To engage my glazed attention a movie need be no classic of its kind, need be neither L’Avventura nor Red River, neither Casablanca nor Citizen Kane; I only ask that it have its moments.” This is very perceptive, in my opinion. For instance, I have a guilty love for teen soaps; I’m currently in season four of Gossip Girl (sound off if you want a GG article). One way to understand teen soaps is as a story that has been constructed to consist as much as possible of its moments.

Metal Gear Solid too succeeds on the strength of its moments. Its gameplay is often annoying, its philosophizing is middle school level. Its characters are parodies of action movie stereotypes. But it achieves a certain alchemy in its absurd too-muchness that transcends its flaws. It is an experience, it has its moments. I came away from it more interested in understanding this formative series and its creator Hideo Kojima. So consider this article a soft promise for an ongoing Kojima Studies series as I play through the remaining games. I know Kojima is only an idea here—I have no quotations from him—but if/when we continue I’ll dig more into him and what he thinks he’s doing with these games.

Enjoyed this. Look forward to your take on MGS2, which I think has the reputation of being the most clever and prescient of the series (though I may be wrong, and biased by the fact that it’s the only one I played through).

I loved this and would love more writing on Kojima plz!