“This is either going to be a piece of shit or people are going to get it”

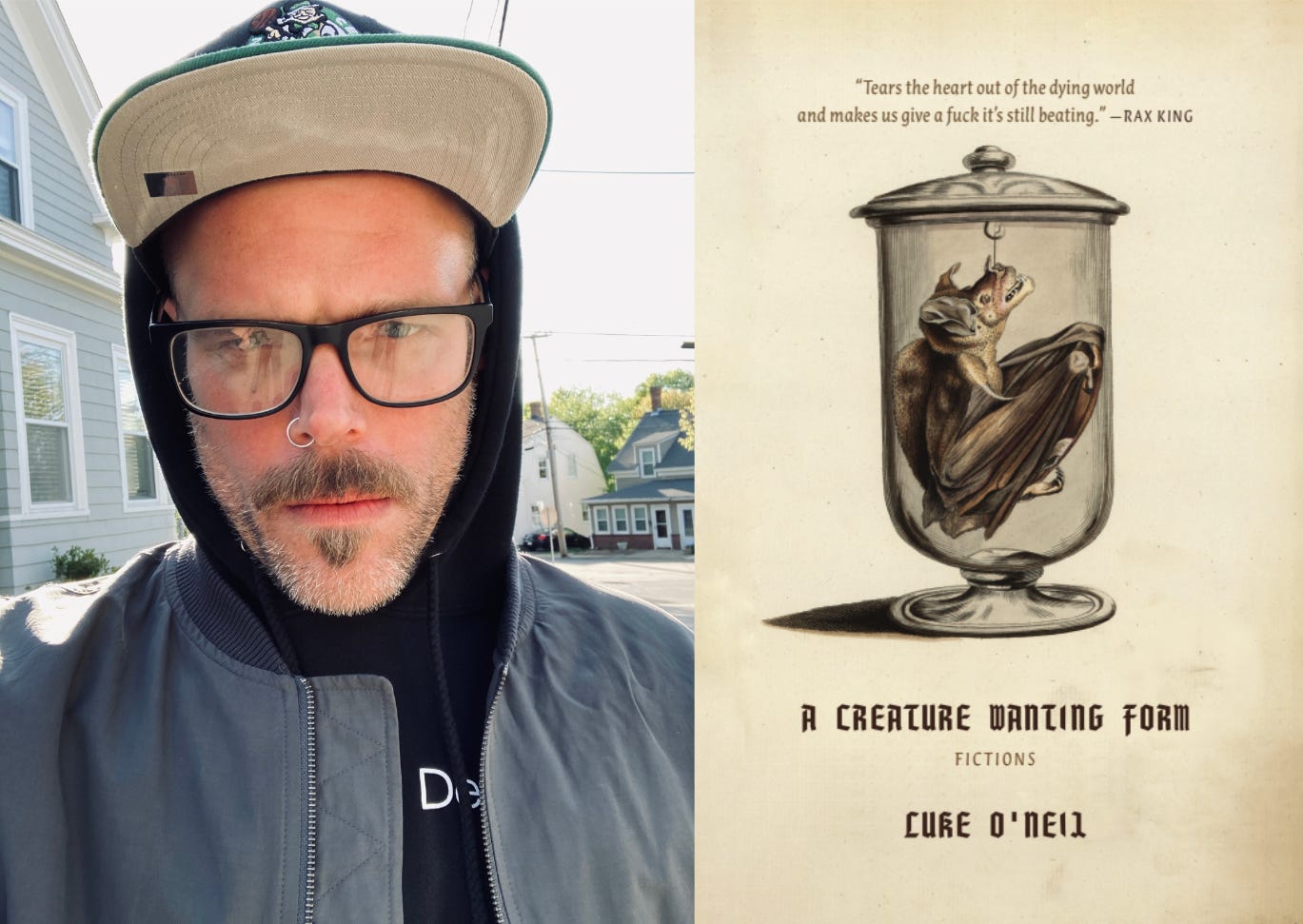

Interview with Luke O’Neil, author of A Creature Wanting Form

Luke O’Neil has long been one of my favorite writers working today, doing vital work covering the inequities and injustices of our country in his newsletter Welcome to Hell World while also writing with incredible depth and humor on personal subjects. He’s now branched into fiction with his new collection of short stories A Creature Wanting Form, which I praised in my last Book Report. I recently spoke with him about making the jump to fiction, useful animal metaphors, and some of his major literary influences. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Danny Sullivan: Let’s start with a little of your background for anyone not familiar and then go into the genesis the new book.

Luke O'Neil: Sure. I've been a journalist for about 20-plus years now. Got my start in Boston at alt-weeklies, Dig Boston and Boston Phoenix were the two. For a lot of my career, I was all over the place. Started out as a music writer and then for a few years I was doing a lot of restaurant and drinking-type of writing, and then started to really focus mostly on politics in the 2010s, and I got frustrated that you couldn't really describe things as they are. Even if you were writing for ostensibly progressive outlets, you couldn't. Anyone who pays attention to the media knows that there's really no such thing as a mainstream Left media.

Long story short, maybe five or six years ago, I was like, "Fuck this, I can't do this anymore. I can't neuter myself anymore." That's right around when Substack was starting and they came to me and asked, "You want to do a newsletter?" And I was like, "Oh no, not really. That sounds stupid and weird, and a lot of work,” but I did it anyways. And I immediately found this freedom to do what I wanted to do and write about what I wanted to write when I wanted to write about it. The newsletter gave me this creative freedom and also weirdly became popular. Next thing I knew, I had some financial freedom and I was making as much as I was grinding out multiple freelance articles a week, just working at my own pace.

So that brings us to the new book. I studied literature in college and did a couple years of an MFA program writing poetry. That's what I wanted to do originally—write fiction and poems. But I put that on hold and went into working at newspapers. But with Welcome to Hell World for some reason I was like, what if I just make this weird? What if I make it sort of journalism, but also poetry and also memoir all at the same time? And sometimes jumping back and forth between each one, sometimes in the same piece. I'm not saying I invented that, but it's not very common, I don't think. That really seemed to resonate with people. And I came to find the pieces that readers tend to like the most were these elegiac, kind of mournful, poetic type of essays.

DS: Yeah. The one that got me hooked on your newsletter, I'm going to butcher the title, but it's something like In the Blue Water Things Are Something Something. It's one of your swimming ones.

LO: Oh yeah, Everything Goes Away or something like that? It's funny, I don't even remember the titles. I kind of fucked myself there. When I started, I was rejecting all the best practices of digital media. One of those is you try to make catchy headlines so it'll grab your eye and you'll know what it's about. So I was like, "Fuck that. I'm just going to make the weirdest sentence from the piece the headline." So now sometimes I'll have to go back and look for an old piece that I wrote, and I'll have no idea what it's called because it doesn't actually convey what the piece is about.

In the water, most of the differences go away. I think that's what that was.

DS: That's it, yeah.

LO: So I hadn't been writing fiction or poems for many years, but I was in a way. I was just smuggling it into journalism. So we put out a couple of book collections of the newsletter, Welcome to Hell World and Lockdown In Hell World. It was about time to start thinking about the next book and we didn't really want to just do another collection of the newsletter pieces. By chance, maybe two years ago, I wrote a couple pieces that I thought would be for the newsletter, but looking at them I realized they were more of a short story, almost like a proper short story.

And then I just put it aside and I wrote a couple others here and there. Eventually it turned out that I had a start towards a book and I decided maybe I should try this. And it re-lit up my brain in a way that it hasn't been in 20 years when I was a serious young literary man who was going to light the world on fire with my short stories. The process of writing it took about a year, and I actually miss it. It was one of the most fun times I've had in a long time, just exercising those parts of my brain that I haven't used in so long. And so here it is.

DS: That's awesome, man. Since you produced the first few almost accidentally, what was it like when you consciously decided the book was going to be short stories and had to explicitly more intentionally commit to doing fiction? Was that a daunting prospect?

LO: It was a little scary because I hadn't been doing it for so long, and I had to put out two pieces a week for the newsletter. That was what was a little bit hard about it because I found myself, and this sounds corny, pouring my soul into all of these stories. It was the happiest I've been in a long time, and if you read the newsletter, I'm not generally a happy guy, but it was just lighting up my brain. A lot of the writing in the short stories is the type of writing that will be very familiar to people who read the newsletter. They just happen to be made up as opposed to true. Last summer was the bulk of the writing for the book, and I wondered if the newsletter suffered for it. I would joke about it in the newsletter sometimes—"Sorry, this one fucking sucks."

DS: I remember you had a line in one issue from around that time where you said, "Sorry it's so much reporting lately—it’s because I'm putting all the other kind of writing into the book." That makes sense in one way, but it's also weird to think about, that in order to give yourself the opportunity to do this kind of more poetic, sensitive writing you had to overdose on news hell even more than usual.

LO: That is kind of funny. And fortunately I also had a great stable of freelancers that I was using a little bit more frequently around that time. People always ask me if focusing on all this horrible shit all the time fucks me up. It does, in a way. How could it not? But at the same time, I live a relatively comfortable life compared to most of the people that I'm writing about. So it's like, I don't really have too much to complain about. I have my own mental health and physical issues that I have to deal with that fucking suck.

That's why it's important for me to make the stories and also the newsletter in general be funny as well, because I don't think anyone would want to slog through all the dour shit without there being jokes strewn throughout or little glimmers of hope. As much as I say I'm not a happy person, I'm certainly a goofy guy who's funny and likes normal shit. I like to watch the Boston Celtics, although that makes me miserable sometimes too. But it is hard to focus on. A lot of the stories in the book use those same themes. There's a couple about school shootings, and there's some about police violence, and climate change and so on.

DS: Speaking of shootings, one of my favorite stories from the book is An International Incident [which is about a guy who keeps lowering the flag more each time there’s another shooting until he’s tunneling into the center of the earth]. That was one that, in this metaphorical, fictional mode, really felt like some sort of portrait of you, having to mark every fucking shooting [in Hell World].

LO: That one obviously is really exaggerated, but is it that exaggerated? That was one that I had the idea for and I just couldn't figure out how to do it. At the community pool where I go swimming, there's a flag and I started to notice every few days the flag was moving up and down. I was like, what the fuck happened now?

DS: It's your Google News alert.

LO: Yeah, but I really was so happy when I finally figured out how to do that one. I just had this idea of the flag going up and down, up and down, up and down. I guess it's a little somewhat on the nose, the story, but I don't know if it is... There are so many shootings. It's just something I have say when I reference a shooting: "Do you even remember which one that was anymore?" There's only so many shootings that you can just hear the name and say, "Oh yeah, I know what that one was." But there's plenty that's like, "I don't really even remember that one." It's so fucked up.

DS: I wanted to talk a little bit more about your writing style itself before we moved on, because I've tried to mimic you a few times and it always comes out as a terrible unstructured ramble. I'm like a comedian doing a bad Norm Macdonald impression. Clearly there's a lot of discipline in your writing. How do you balance some of that stream of consciousness with shaping it into something more coherent and, so to speak, good?

LO: It takes a lot of work to make this shit seem so off the cuff. It depends on story by story, but some of them, I literally just sat there and it just all came out. But then of course I go back and rewrite it many times. I edit it over and over again. I still somehow miss typos when I'm doing that in the newsletter, but rest assured that I rewrite these things five, ten times. And the stories for the book, I must have written some of these 50 times, or at least read them over and over again changing a word here and there.

There's a rhythm to it that’s the tipping point for people who either, some people love my shit, and I'm sure plenty of people think, "What the fuck is this? This is nonsense." And that's fine because I don't think it's for everyone, but there is a rhythm to it. And there has to be, when it's stream of consciousness type stuff, especially with no commas, the sentence length and structure variation has to provide some of the pauses that you might normally get from typical punctuation.

DS: Counting your iambs.

LO: Not really because I forget all of the actual technical poetry stuff that I learned. I literally do. It's been a long time but I can just sense it in there. When I go back and edit it, I’m just like, "Okay, this sentence needs to be a departure from the sentence before it." And then, "Oh, here's just a three word sentence here. This is going to break up the pattern." It really does take a lot of tinkering and I will labor over a word choice. It's fun to do Norm Macdonald's thing where archaic words are just kind of funny when they come out of nowhere. It took me a while to realize that Norm was such an influence. I’m not anywhere remotely as funny, obviously, but that spinning a yarn type of thing, like an old timer telling a tale on the porch. People loved that about him, just the word choices he had.

So I do that a lot. I write the thing and then go back and look, all right, which of these words can be replaced with a funnier, older sounding word? I think that's something like George Saunders does too. There’s that contrast in some of my stuff and some of his stuff. They're sort of futuristic, sci-fi-ish type things, but they're being told in this matter-of-fact way. Marvelous things are being described matter-of-factly. That, I think, is the throughline throughout this book of short stories of mine.

DS: Some of the biggest laughs I got from the book were some of the pop culture references you threw in—the fox doing Jim Face at the camera, and the fish thinking about fish Jodie Foster, “they should have sent a fish poet.” One thing I noticed is that you use a lot of those specifically when you're going inside the mind of animals, so I thought that was interesting. But was that something you worried about or thought through? Were there pop culture references that you decided to scrap because it was too many or you worried it was hack?

LO: Oh, probably. Actually, in the fox piece, I wondered if it was going to be too much to do Jim Face.

DS: And the Oldboy reference?

LO: Jim Face and Oldboy and Michael Jordan. Is that too many? Am I stacking too many in there? But I think that's actually one of my favorite pieces from the book. Where it says, “It must have looked like the hallway from Oldboy in there,” you can picture it. That's a very vivid image for anyone who's seen that movie. I sort of loved the idea of this fox. That was based on a real thing that happened. I don't know if it happened like that, but I read a headline where a fox broke into a penguin enclosure and killed two dozen penguins. I wrote, “How does a fox do that?"

Then I was trying to think, "Okay, what's an example that people will recognize of people playing out of their minds?" That Jordan game is a famous one, but that was actually a hard choice to make. What was there? I don't know, Tom Brady against Atlanta or something like that. I like that it was kind of an older reference.

I don't know why I have so many with animals. Obviously, it's a good way to smuggle in a metaphor about humans when you anthropomorphize animals. I don't know if it's a cheap trick or not, but it's a trick. When we do that, it lays bare the cruelty and baseness of humans, which seems like an obvious thing to try to do. One of the titles we considered for the book was something like The Ants and the Plants and the Animals Eat Each Other, which is a Modest Mouse lyric. I have a line in there, I forget exactly, something like “The universal condition of all animals is that we're starving and just looking for the obvious antidote to that, which is to eat each other.”

And then there's a line in one of the stories about seagulls—there are a lot of fucking seagulls in the book. The reason for that is for the first two years of Covid like a lot of people I barely went anywhere except for the beach. I'm a big Maine guy. We've been going to Maine most of my life, so a lot of these are set in Maine, specifically Kennebunkport which is a place that I go every summer. And a bunch of them are set on the north shore of Massachusetts, like Newburyport. Those are two of my favorite beaches.

And then there's one that I quite liked about the cop planting drugs on the lady, and he's basically a spider. So maybe it sounds obvious when you're spelling it out like that, but I found it to be effective. I really liked how that interplay worked out.

DS: Moving on a little, let's talk about some of your influences, starting with Virginia Woolf. You've talked a few times about what an incredibly formative book To the Lighthouse was for you, which I was trying to think about, and it is a book about living an artistic life in an incredibly harsh world.

LO: Yeah, there's a lot to that.

DS: Woolf is such a master of rendering stream of consciousness and her characters’ inner lives. I thought you did a great job in this book of twisting that into rendering distraction. I wondered if you had any thoughts about that distinction, if that was something you were trying to accomplish.

LO: It's been years since I read her extensively—I basically gorged myself on Virginia Woolf in college and grad school, but I’m by no means a scholar of hers anymore. But if, by distraction, you mean like all the characters in the book are never fully present in where they are and they're often looking at their phone?

DS: Yes, exactly.

LO: That is a device that does a couple of different things. Obviously, first of all, most people are constantly looking at their phone now, but I've never really seen anyone accurately capture that aspect of how it is to live now. Because you can just be there having the most meaningful, poignant, or distressing experience that’s happened in your life, and you're going to look at your phone anyway. That's a part of life that doesn't necessarily get captured as much in fiction. They try in TV and movies now, they do a little bit better job of showing people texting and stuff.

The other thing that device does is it provides you a window to the world in a way, if that doesn't sound weird. In the context of a story, it would be weird if some guy was just at the beach and all of a sudden you just started talking about some shooting going on somewhere or something, a storm happening in a different state. But being able to say, “He looked at his phone and there was a shooting going on.” That brings the entire world to the small setting of the story in a way that I thought felt natural to how our brains work now.

In a straight-up poem, you can kind of jump all over the world. But in a short story, you want it to be a little more point A to B. Or there's some scenes where the guy’s glancing at the TV, I guess that's an older type of trick to do it. Here's something thematically resonant that's happening elsewhere that kind of colors the mood and the tone and the themes of what's happening to this person.

DS: Let’s move on to Donald Barthelme. He's an interesting guy to me because he strikes me as someone who lives more on the strength of his ideas than straight up on the prose, so to speak. He's a good writer, but he's executing ideas, in my opinion. Do you agree with that?

LO: Super high-concept guy, for sure, which is why a lot of his pieces are very short. You wouldn't want to read that type of stuff for too long, and a lot of his stuff is really impenetrable and hard to get into. But when he nails it it's just the perfect crystallization of these high concept things—a picture of our world that's just slightly off, heightened reality a little bit. And funny. The School, for example—one of his most famous stories—for all of the darkness to it, it's just extremely funny. So on a sentence level, I'm certainly not going to criticize him when I'm a guy walking around doing knockoffs of his type of stuff. But I think he, perhaps more than anyone else, unlocked something in my brain 25 years ago when I first started reading him. I would take being compared to his stuff as a compliment, but if you really want to know, I have surpassed him in talent, in artistic achievement. [laughs]

DS: I’m glad you brought up The School because I wanted to ask you about that specifically. My favorite part in that story is toward the end when the school kids suddenly start talking like grad students.

LO: Yeah.

DS: "And they said, is death that which gives meaning to life? and I said, no, life is that which gives meaning to life. Then they said, but isn't death, considered as a fundamental datum, the means by which the taken-for-granted mundanity of the everyday may be transcended in the direction of—" The School is hardly realism, but that's the moment where the whole story breaks open and, whatever it was, now it's something else. And to me, it's amazing. But it feels like a moment where if I were writing, I would be terrified that the audience isn't going to take that leap with me. You have a lot of moments in your stories where you ask the audience to take a leap like that. And I'm wondering, first of all, where does that courage come from and how do you navigate that?

LO: I was scared shitless on some of them. Some of them are like, "Oh my God, this is either going to be a piece of shit or people are going to get it." I tied myself into knots worrying about some of them like that. When I use words like "scared" and "courage," obviously we're talking about writing short stories, so let’s not take this too seriously, but eventually my instincts kick in like they did when I started the newsletter. I had to be like, "Well, fuck it. I'm either going to live and die on my goofy shit."

But to return to that passage you referenced, what I try to do is—I don't really have a better term for it—I call it the trap door. So it's when you're reading something and then a trap door opens and you fall through it, and now you're down on a next level beneath, and it reveals everything above to be something that you weren't prepared for.

Kind of like an a-ha moment. It’s something David Berman, who is another influence, and his book Actual Air, does really well. It would just be one line towards the end that retroactively—"Oh, that's what it was about. Okay, I didn't know what this was actually about. Now I do.”

DS: Cool, man. I don't want to keep you too much longer.

LO: No, this is good. I've talked about myself. I don't really like doing this, but I appreciate you thinking about the book. Having any reader read your stuff closely is great, so I appreciate it.

DS: I really loved it. It's really good.

LO: Now if we can get a 100,000 more people to say that, I'll be sitting pretty.

Subscribe to Welcome to Hell World and buy A Creature Wanting Form now.