Okay gang, I’ve already written two intros for this month and hated both of them so instead let’s play a quick round of Guess The Book. The only rule I have with these reading reports is that I include books for the month in which I finished them, not when I start them. Usually this is a distinction without a difference but it becomes an issue with longer stuff.

I’m currently working my way through something quite long in between reading the books included below. It will show up in a future book report, but in the meantime see if you can guess it. Here are some clues:

First published in 1890

It was published in three editions, getting longer each time

The third edition ran twelve volumes, published over the course of a decade

Material in the second edition was highly controversial and was omitted from the third

I’m reading the “New Abridgment” which restores that cut material and runs 800 pages

Cited by TS Eliot as a major influence

Also influenced Freud, Jung, and Gaddis, among many others

Any ideas? Comment them down below!

I don’t make any money from this newsletter but I still want to grow my subscriber base. If you enjoy these posts or have a friend you think would like them, please consider sharing my work on social media or forwarding this email. Thanks and here’s what I’ve been reading this month.

The Baron in the Trees, Italo Calvino, 1957

In 1757, at twelve years old, Cosimo di Rondo climbs into a tree and never touches the ground again. He and his family are minor nobility in Ombrosa, a coastal region of Italy that’s heavily forested; far from being trapped in his family’s yard, Cosimo’s kingdom of trees is boundless. His life’s story is recounted by his brother in old age, who remained thoroughly conventional and never mustered the courage to join his brother among the boughs.

Cosimo learns to navigate his new highways of oak, elm, and olive, first falling in with fruit thieves before going his own way. Calvino anticipates with uncanny accuracy the questions his reader is asking and the objections they’re raising, walking through how Cosimo feeds himself, clothes himself, bathes himself, and sleeps up in the branches (and in which situations he accepts help from ground dwellers). As he grows up he becomes at times a leader of the community, organizing fire brigades and wolf patrols from his perch.

What does Cosimo find in his retreat to the treetops? He never quite says. He’s driven by an inner conviction—an ideal, he says late in the book—but he’s taciturn on the specifics. He renounces his titles and properties but whatever liberty he finds up there is not one of pure withdrawal. He remains in contact with his family and society more broadly, he reads voraciously, and carries on several major love affairs. This is not Thoreau’s retreat to Walden, which seems on closer inspection more like self-imposed exile than true freedom. Cosimo’s life is circumscribed by his choice to live in the trees—he never marries or fathers any (officially recognized) children—but in his strangeness is given total leeway by the community to comport himself according to his principles, whatever exactly they are.

I’m loving Calvino more with each book. His work has the same quality of Umberto Eco’s (more on him some other time) of deep intellectual sophistication couched within exceedingly enjoyable stories. What is it about the Italians?

One-Way Street, Walter Benjamin, 1928

This is a cool one. Benjamin, to my mind one of the wittiest, most dynamic thinkers of the 20th century, appears to have walked down a street and written down a list of the shops, signs, and wares on display and then used that list as inspiration for aphorisms and reflections. A pair of gloves gives rise to a consideration of the root of an aversion to animals; an advertisement exhorting Germans to drink German beer occasions a thought about mob mentality and nationalism.

To read Benjamin is to experience the greatest hope and greatest despair. His mental dexterity, jumping between topics and drawing out their hidden connections, is what I covet and what I imagine I’ll always fall short of. He’s so fun to read—so funny, looking around him at the looming crises of the interwar period with a wry remove that lets him be perfectly honest about those crises without descending into resignation or hysteria. He was just the best and the inventiveness of his ideas was matched only the inventiveness of his literary experiments, as this book shows.

A Creature Wanting Form, Luke O’Neil, 2023

We longtime readers of Luke’s banger of a newsletter Welcome To Hell World divide his work into two general categories: there’s his political stuff, about how the cops love to kill us and how insurance companies love to kill us and even our good politicians love to watch us being killed and do nothing, and his personal stuff, about Irish Catholic self-loathing and swimming in the ocean and waiting to die in a more banal way. Those latter we label “one of the good ones.”

His new book of fictions is all good ones. These stories, which run from two paragraph half-pagers to ten pages tops, are written in the tumbling, digressive style he’s honed in Hell World, thoughts and action coming uncoupled as experience and outer reality vie for supremacy. Some stories are little more than setup-punchline (see Proverbs), while others build out entire dystopian scenarios through minimal suggestion. In either case Luke has a great grasp on one of the most important tasks of the short story, which is knowing when to cut it off.

Luke said that a lot of these stories are going to be accused of being George Saunders ripoffs—and you can definitely see that influence in for instance the story about the guy digging down into the center of the earth so he can keep lowering the flag in commemoration of more mass shootings than he can keep up with—but said further that actually they’re George Saunders ripping off Donald Bartheleme ripoffs, which is both true and a pretty good joke. But for my money the biggest influence here is Virginia Woolf, whom Luke has also avowed as a major contributor to his style, despite her love of commas and his sheer hatred of them. Woolf’s great gift was simultaneously rendering the inner and outer lives of her characters, a skill which Luke has inherited in full. So many of these stories concern bizarre happenings juxtaposed with characters who are so wrapped up in their heads they barely notice, as in the story about sinister smokestacks rising from the sea and sucking in anything that comes near seen through a narrator far more concerned with justifying to himself why he chickened out of asking his coworker on a date, insisting to himself he’ll do it next time.

A Creature Wanting Form really gives you the full Luke buffet: funny, crushing, surprising, and existentially terrifying, all rendered in prose that’s like nothing else out there. Sometimes I hope he sorts his shit out but then where am I going to get writing like this?

ONE GOOD LINK

Harper’s: The Age of the Crisis of Work—The compelling thesis of this piece is that we are in the midst of a “legitimation crisis” regarding work. The author cites Habermas and his schema of the types of crisis that can trouble a society: political, economic, motivational, and legitimation. The old scripts telling us why work matters and how it can be meaningful are exhausted now that nearly every job left is a bullshit job that still doesn’t pay enough to build a good life, leaving no legitimacy but the cruel logic of poverty.

KIDS CORNER

The Princess and the Goblin, George MacDonald, 1872

MacDonald, a Scottish poet and minister, is now credited as one of the seminal authors of fantasy literature as it slowly gestated over the first half of the 20th century before exploding following the popularity of Narnia and Lord of the Rings. Tolkien’s orcs are supposed to have been heavily based on MacDonald’s goblins, living as they do within mines inside mountains. Naturally I had never heard of him until a couple months ago.

With that pedigree, it brings me no pleasure to report that this book is awful. Tedious does not begin to describe it. MacDonald is so focused on the minutiae of process that he fails to tell us almost anything about the world around it. His vision of a kingdom and a princess and a castle is so barebones. Instead every scene is characters doing dialogue back and forth to make the most basic decisions. “Should we follow this boy back home, since we’re lost?” “Well, he says he knows the way.” “Yes, he could lead the way.” “Then we shall.” I expected MacDonald to have been an engineer by trade.

This book is just not rewarding. Curdie, a miner boy, discovers the goblins who live below them are planning some sort of offensive against the surface. He goes home and tells his father. Then the king arrives. Does Curdie’s father report what they’ve learned? No, nothing happens. Then a year passes—still no goblin attack. It’s so aimless. Also, practically every scene with the titular princess, Irene, is just her getting scolded by the adults in her life—it’s really a bummer and decidedly not magical. We bailed on this book after 60 pages. Patrick didn’t seem into it and reading it out loud was making my jaw hurt.

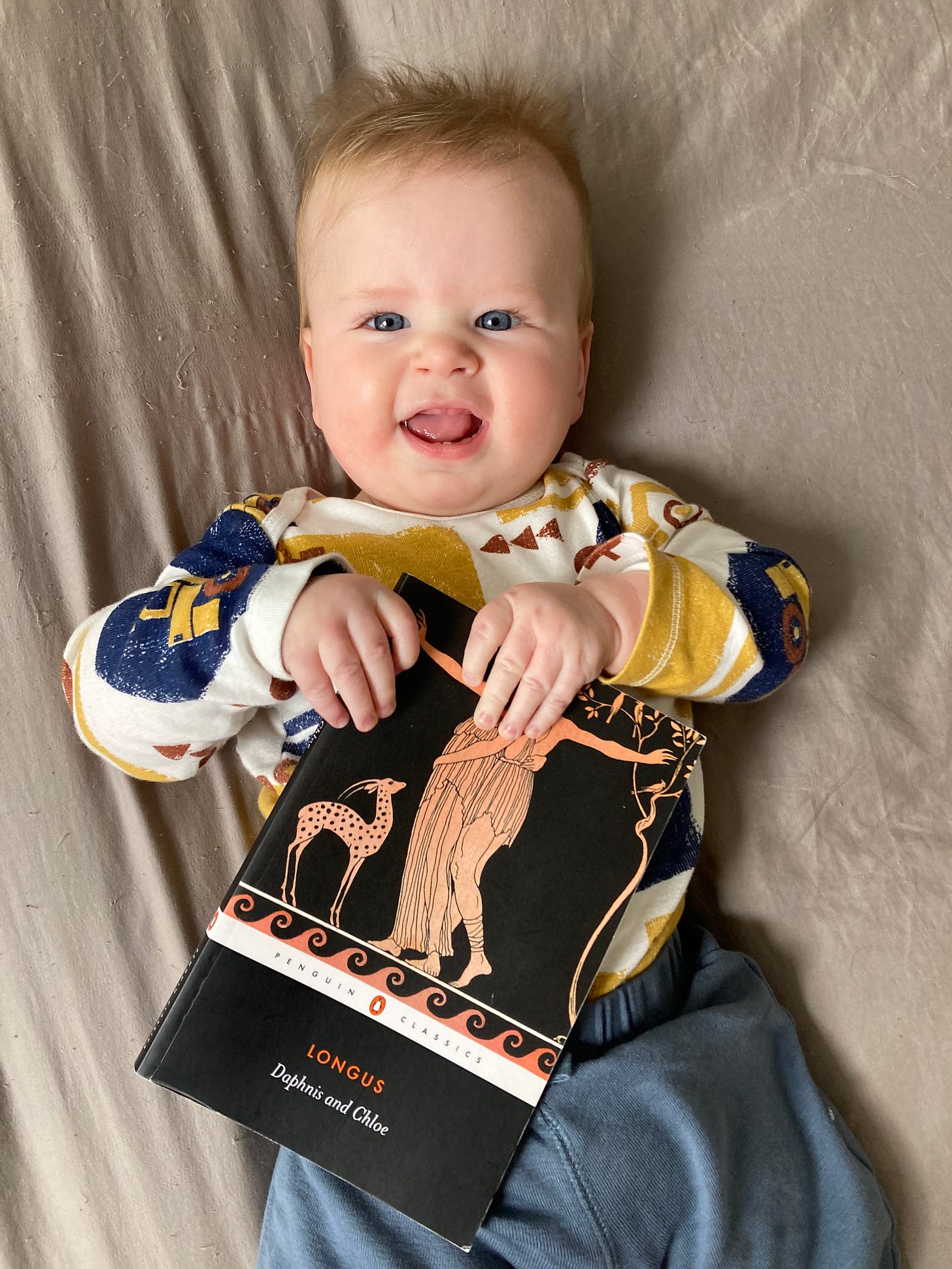

Daphnis and Chloe, Longus, circa second century CE

Hooooo boy we’ve finally found the line where I’m nervous to report that I read this to my baby. This pastoral story, set on Lesbos, concerns two children found abandoned with tokens of noble birth and raised as shepherds and goatherds. Fast forward to their teen years and they spend all their time tending their flocks, playing the pan-pipe, and being madly in love with each other. It’s cute, the nature descriptions are pretty, and the episodes that throw roadblocks in their way are never too serious.

It’s also uhhhh very horny and a lot of the story concerns their desire to get it on and being stymied by literally not being able to figure out the mechanics of it. So those passages are not great. But that’s why we read the classics right? To step outside our paradigms of taste and conventional morality, which is a very important exercise for an eight-month-old, right? Anyway moving on, this book is nice. Don’t call the authorities on me.