Assorted thoughts after reading Crime and Punishment

A quick list

Dostoevsky turns out to be one of the only classic authors where I care about spoilers. I had a friend get mad at me once because I mentioned offhand that Anna dies at the end of Anna Karenina. I couldn’t believe he was serious because, first of all, it’s a book from 1878 but more importantly it’s a book where a woman commits adultery—how else do you think this is going to go bro??

Going into Crime and Punishment all I knew was that the main character was named Raskolnikov and he was going to commit a murder. Genuinely not knowing how things would play out let me appreciate that Dostoevsky is a master of suspense. Raskolnikov’s escape after the crime is so tense! It felt totally plausible he would be caught immediately and the rest of the book would be his trial and imprisonment. And then conversely I really enjoyed discovering that that is not at all how it goes.

I had a really intense experience with Demons the first time I read it but when I revisited it a couple years ago I found it much diminished. Part of that was I had completely blocked out how much of the story focuses on Stepan Trofimovich and his stuff is so boring, but even the Stavrogin/Verkhovensky stuff underwhelmed; Demons finds so much of its power from its long, slow build-up of dread as the fete approaches and our never being quite sure what Verkhovensky is capable of. I wonder if my sense of deflation was the result of all that suspense and uncertainty being a closed question.

Dostoevsky had been reading Plato, specifically The Republic, when he was writing Crime and Punishment. Liz saw me reading C&P and was inspired to pick up Notes From the Underground. She was telling me her impressions and was worried she was projecting something that wasn’t there but was feeling a huge indebtedness to The Republic—the underground as The Cave and so on. This was affirming for me because I had been getting Republic vibes from Crime and Punishment and was worried I was projecting. (The two books were written basically in succession, with Notes published in 1864 and C&P in 1866.)

Raskolnikov kills the old woman because he wants to “step over the boundary,” the boundary that separates ordinary people from the extraordinary. He invokes Napoleon, whose greatness was built on his willingness to follow courses of action that most people couldn’t even imagine, as when he abandoned his army in Egypt and returned to Paris without giving a thought to their fate. Raskolnikov further elaborates the idea in a scene with the inspector Porfiry. They discuss an article Raskolnikov published months earlier in which he claimed there is a class of people who have a right to commit crimes. He glosses it thus:

I merely suggested that an “extraordinary” man has the right… that is, not an official right, but his own right, to allow his conscience to… step over certain obstacles, and then only in the event that the fulfillment of his idea—sometimes perhaps salutary to the whole of mankind—calls for it. [...] As for my dividing people into ordinary and extraordinary, I agree that it is somewhat arbitrary , but I don’t really insist on exact numbers. I only believe in my main idea. It consists precisely in people being divided generally, according to the law of nature, into two categories: a lower or, so to speak, material category (the ordinary), serving solely for the reproduction of their own kind; and people proper—that is, those who have the gift or talent of speaking a new word in their environment.

I imagine many readers now hear Raskolnikov describing something close to Nietzsche’s ubermensch. But his specific formulation reads to me as a modification of the Noble Lie from The Republic, which claims society is composed of three classes people defined by their innate nature: the gold souls, fit to rule; the silver souls, helpers or guardians, variously; and the bronze souls, farmers and craftsmen.

Raskolnikov’s schema is just a recapitulation of Plato’s, minus the silver souls. This tracks with the milieu of the novel. In Richard Pevear’s introduction to The Idiot (if memory serves) he remarks that it may seem puzzling that nearly every character in that book is either a civil servant or a military officer, but that for the middle class this was basically true to life in the 1870s—those two fields were basically the only ones remaining that could support middle class existence. The Idiot is an exceptionally middle class novel which makes it a silver-souled novel.

Crime and Punishment features no civil servants (save the drunken Marmeladov, who can’t master his vice to hold his job—he’s a bronze soul masquerading as silver) and no military men. Its characters are either destitute or obscenely wealthy. Raskolnikov forgets the silver souls because they are nowhere to be found, although perhaps Porfiry and the other police officers would qualify. This is a story about those dregs of humanity at the bottom of the hierarchy, although Dostoevsky is clear that our natures are not fixed and circumstances can either degrade or ennoble a person. Poor Katerina Ivanovna, dying of consumption, was a colonel’s daughter and was raised to be part of the upper crust but finds herself destitute and destroyed. Wealthy merchant Luzhin is a petty and vindictive liar at bottom, hardly the gold soul he imagines himself to be. Raskolnikov is so desperate to escape his circumstances he manages to convince himself the Noble Lie is true. If he could simply demonstrate his gold soul bonafides a path to the top of society would be soon to follow.

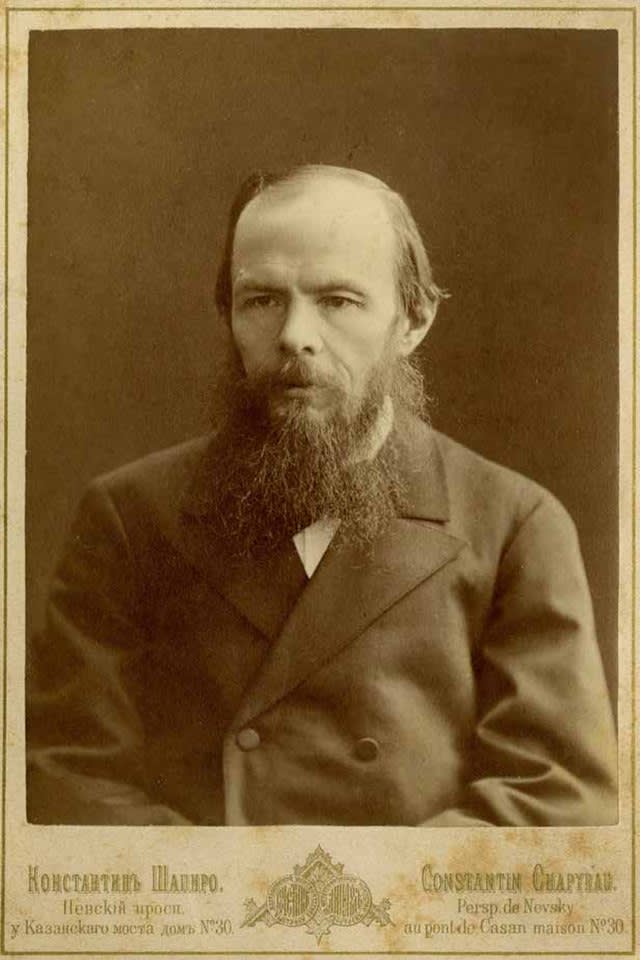

At one point Jack Nicholson and Dostoevsky looked a lot alike, in my opinion. Missed biopic opportunity.

I was reading Crime and Punishment and Tam Lin at the same time. So I had, on one hand, a cast of characters with names like Avdotya Romanovna Raskolnikov, Semyon Zakharovich Marmeladov, and Arkady Ivanovich Svidrigailov and, on the other, Janet, Peg, Molly, Tina, Nora, Anne. Gotta say I had a lot harder time remembering who was who in Tam Lin!! I’ll take Russian patronymics over a bunch of interchangeable Boomer girl names any day.

Dostoevsky was a much bigger influence on William Gaddis than I had appreciated before. For all his books after The Recognitions, Gaddis wrote almost exclusively dialogue. Therefore, it falls on his characters to convey through their speech the physical action of each scene. Without taking anything away from Gaddis, who is inventive with the way his characters clue us in on the action, I now see how directly he has lifted this technique from Dostoevsky. Here, for example, is Katerina Ivanovna’s narration when Luzhin has accused Sonya of stealing from him:

“Anyone you like! Let anyone you like search her!” cried Katerina Ivanovna. “Sonya, turn your pockets out for them! There, there! Look, monster, this one’s empty, the handkerchief was in it, the pocket’s empty, see? Here, here’s the other one! See, see?”

Dostoevsky is not averse to narrating action like Gaddis so what this technique accomplishes is to keep us in the scene and to maintain the breakneck pace of the characters’ hysterics. Gaddis will adopt it at scale to depict an entire world rushing hysterically forward without pausing to take a breath.

Another, smaller bit of consonance between the two authors is the way they choose to deprive us of our main character at what seems the pivotal moment. After following Raskolnikov in lock step the entire novel, as we approach his last day of freedom, he parts ways with Svidrigailov and the narration follows Svidrigailov instead. We never get to see what happens to Raskolnikov in that time period; by the time we return to him the day has passed. I was reminded of how in JR, after dynamically following the interlocking storylines for hundreds of pages, the narrative perspective finds its way into the flophouse apartment that has become filled with the drop-shipped detritus of JR’s paper fortune and gets trapped there. Time continues passing but we can’t find our way out. As things come to a head we only get the scraps that various characters bring in and share.

Here’s an intrusive thought I need to purge. There’s a footnote in the P&V edition of Demons regarding a real-life anarcho-communist group that Sergei Nechaev, one of the chief inspirations for Demons, belonged to. The revolutionary group was called The Committee of the People’s Summary Justice of 19 February 1870 and their tracts and pamphlets carried an oval seal of an axe with the group’s name encircling it. Try as I might I cannot find any reference to this group online or an image of this seal. I feel like a baseball cap with that seal on it would have made sweet merch for the dirtbag left like eight years ago.

The TV series Columbo was inspired by Crime and Punishment, and it shows: In each episode we first see the murderer commit his crime, and then we follow the detective's pursuit, circling around the guilty... until the guilty has no choice left but to confess. (However, Raskolnikov was poor. In Columbo, the murderer is almost always arrogant upper class, a contrast to the humble working-class detective.)

Fascinating! Thanks for all the insights.