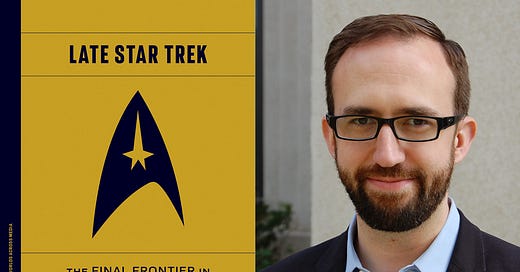

Last week I reviewed Adam Kotsko’s new book, Late Star Trek: The Final Frontier in the Franchise Era. The book is a highly enjoyable and thought-provoking read that was perfectly timed in my life as I finished watching Deep Space Nine (a top-ten all-time tv show, in my opinion) and started Voyager (it’s fine). Adam is the author of numerous books including Neoliberalism’s Demons: On The Political Theology of Late Capital, which I also read recently and highly recommend. Adam and I spoke before I wrote my review and a couple sections reproduced here were quoted in it already. In our full discussion we talk about his journey to becoming a true Star Trek scholar, the eternal problem of canon, and how his analysis of late Star Trek fits with the broader themes of his work. Our conversation has been edited for length, clarity, and filler words.

Danny Sullivan: Adam, quick, there's a warp core breach imminent. Explain the difference between a branched timeline and the Mirror Universe without resorting to the phrase “different ontological status.”

Adam Kotsko: [laughs] A branched timeline is caused by altering an event in the past, and the Mirror Universe just was always separate… yet somehow tied to ours? That's the best I can do.

Danny Sullivan: I'm interested in how people come to be Trekkies because my impression has always been you either get into it as a kid or you never get into it at all. So I guess I'm sort of an outlier in that: I've just started watching it in my thirties. It seems like that's not very common, so I'd love to hear: what's your history with the franchise?

Adam Kotsko: My dad always enjoyed it. I have memories of watching this weird show with these big primary-colored people in it when I was very young and then I had a weekend ritual of watching Next Generation when I was in junior high into high school. I even got so far as to start reading some novels. I was getting into it, but then when high school hit, I thought, “This isn't going to play.” I was more interested in potentially attracting a girlfriend than keeping up on fictional TV shows, and I made the shortsighted decision to stop my exploration of Star Trek. But then as an adult, my girlfriend, who is still my partner now, suggested we watch Star Trek: The Next Generation together. Then it just absolutely ballooned. Once I gave myself permission to get back into it, I was suddenly watching all the shows. I was digging back into novels. I was getting involved in fan discussions. There was apparently pent up demand over those decades.

Danny Sullivan: It's such a different style of storytelling. It really took my wife and me a minute to get on its wavelength being used to more modern stuff— you start an episode of TNG and in the first 10 minutes you're like, “Okay, I have to commit to this Riker storyline and I know it's going to be resolved in 45 minutes.” And at first it almost makes you feel itchy, but then you get used to it, you watch the show enough and it becomes this different sort of pleasure, wouldn't you say?

Adam Kotsko: I agree. I think it's a feature, not a bug, that every plot needs to be resolved. The problem with streaming TV is that it can never end. There's something in the human mind that needs a storytelling unit of maybe one or two hours; the 10 hour movie format simply doesn't work. But even in that context, I think that Star Trek is a little bit slow-paced compared to today, especially Next Generation. It does take some patience, and especially if you've figured out the solution to that week’s problem before the characters, it can make you pretty impatient. Why aren't you asking whether Geordie’s possessed by an alien when these things happen all the time? Why does it not occur to you to ask?

Danny Sullivan: So you got back into all of it with your partner, and the book grew out of the thoughts that was inspiring?

Adam Kotsko: I was participating in these fan forums and starting to get skilled at seeing what their tics were. It seems like it's common sense to them that Deep Space Nine is the best one, and I think they say that simply because it's the one that's least accessible to somebody who's not obsessed with Trek. But it was really only when I got to Enterprise that the seed was planted because I had heard the terrible reputation of the show. It's widely panned, and one of the biggest topics, at least before Discovery came out, was to try to write Enterprise out of the timeline, to come up with some reason that some time travel event had happened and it had actually forked, and Scott Bakula had never been captain of the Enterprise in any form, because it was just unacceptable that this was considered part of Star Trek.

And the theme song is really bad. It's a cheesy Rod Stewart song as opposed to the orchestral songs. And so when we first watched it, we got to the theme song and we were just like, “Oh my God, what is happening?” But the mute button exists for a reason. And so once we decided that we were going to mute it, we realized this is kind of in the ballpark of what we'd seen before. It's similar quality to Voyager. At least the highs are not as high, but the lows are not as low either. The revulsion that people had to it was just disproportionate, I thought. And so I became the resident Enterprise apologist. I launched a million theories about it, I wrote so many posts on this forum, which is called the Daystrom Institute, about Enterprise, and I intervened in so many discussions trying to write Enterprise out of the continuity. This is when I became a true Star Trek scholar, this over-analyzing of Enterprise, which I admit is one of the weaker installments.

I think in my heart of hearts, I wish that I could have written a book that was just about Enterprise, because I do have some thoughts that I left on the table that are not present in that chapter, if you can believe it. But I'm sure that almost literally nobody would want to read that book. So I had to expand the purview a bit.

Danny Sullivan: Enterprise is a natural starting place for your book because it seemed to be the point where the franchise’s canon changed from something rewarding to hardcore fans to something problematic. It’s when we go back into the past where suddenly all of the established facts of the world become this really imprisoning force on the storytelling. What were the positives of establishing and paying homage to so much canon in Star Trek, and when did it become such a problem for the franchise?

Adam Kotsko: The concern with canon started early and was partly inspired by fans. Fans would notice inconsistencies between episodes of The Original Series and they'd write in; eventually they hired somebody whose job it was to answer those questions and try to come up with the answers. And so it was really driven by fan investment and their desire. I think their desire was to see Star Trek as a real world. I think Roddenberry and his team probably intended for it to be more of a loose episodic concept when they first did it. I think it was in response to fan investment that they started thinking in terms of canon, but then there's always been this countermove to ditch things from canon.

Especially once The Motion Picture came out and they suddenly had much better production values. The film wasn't great, but it looks better than The Original Series. And I think that looking back, The Original Series seemed like an embarrassment, and I think that Roddenberry wanted to say, “That's not canon. Those are legends now or whatever. And the real thing is going to be the movies.” In the early seasons of Next Generation, even only the movies were really considered binding canon.

What really shifted in the reception of canon was when Deep Space Nine came around. It had such a radically different concept from Next Generation, a very different approach, a very different tone, and they were anxious to prove that they were still really Star Trek. One way they did that was by just increasingly incorporating more and more Original Series references like the Mirror Universe and the Orion Syndicate. They even put the cast in an Original Series episode Forrest Gump-style.

Danny Sullivan: The passage in the book about that episode of Deep Space Nine, “Trials and Tribble-ations,” is so great. How the production design of The Original Series had become this major sticking point for these hardcore fans who wanted to say, “No, it literally all looked like that—all of that cheesy, crappy 60s set design and stuff is true. That's the future.” So when they sent Sisko and company back to that time that meant the visuals had been canonically sanctioned, the look of The Original Series was canon because it was canonically sanctioned by something else that was canon, an ouroboros of canon.

Adam Kotsko: Or a human centipede. It causes so many problems too—an obvious joke that the Klingons didn't have forehead ridges back in The Original Series because they had a low budget and then they made them look more alien in subsequent productions. But Worf says, “We don't talk about this.” And fans took that to mean that they really somehow lost their ridges for 30 years and then grew them back. It's absolutely crazy. That's what they took away from it, not that it's obviously a joke. It's a joke, but if it's canon, if everything is treated as though it's a real event in a real world, you can't dismiss it as a meta joke because there is no fourth wall to break.

The idea that it's all a unified canon was actually pioneered by Deep Space Nine and that episode was the biggest example of it. And it just became a noose around their neck.

Danny Sullivan: The other example that occurs here to me is that it's so strange that the JJ Abrams movies couldn’t just say, “Hey, it's a different imagining. Don't worry about it.” Instead that first movie has to slam the brakes for 20 minutes for Spock to explain the mechanics of how it's a different timeline, but then that weirdly does put it into the canon, and the Romulan supernova then is part of the Prime timeline. That was such an unforced error that I thought was catastrophic when I saw that movie as a Trek neophyte.

Adam Kotsko: It’s such a lose-lose, right? By touching that third rail, you're only going to piss off the fans and you're losing the new audience. I think maybe their reasoning was that was the only way they could get it on-screen—that it was a clean reboot and everything was up for grabs. But then they have to incorporate this meta gesture into the text of the show. That's what my book is basically about: how Star Trek keeps creating these stories that reflect the intellectual property dilemma they’re facing in our world.

Danny Sullivan: You say that early in the book that the stories of the shows have become increasingly reflective of its fraught place in the marketplace that's continually in danger of cancellation while also being asked to do more and more for its corporate parent. I thought it was really interesting that Voyager and then Enterprise were conscripted as the tentpoles for UPN to try to be a real network. And now 25 years later the new batch of shows are performing the exact same role for Paramount+. It seems like such a strange thing that Star Trek, this famously niche property, has been asked to do this twice over.

Adam Kotsko: Especially expecting Enterprise to succeed where Voyager had failed was foolish. Why would they just double down on this failed strategy? It seems like they’ve had somewhat greater success with Paramount+, but we have no way of knowing for sure because they're famously cagey with numbers on streaming viewing, and they're culling shows that fail to find a big enough audience, as has happened to Prodigy. I don't know how much longer this era is going to last. Star Trek is in this negative sweet spot where it's not big enough ever to be Star Wars, it's never going to be Marvel. It's never going to be one of these truly huge properties, but it's big enough that it keeps inspiring these misbegotten corporate schemes.

It's really deeply unfortunate, and it was the aspect of my research for the book that was most discouraging: looking at the corporate side of things and just how badly mismanaged it all was. An important reference point for me here is an article called Franchise Fatigue by Ina Rae Hark. She emphasizes that people talk about the fortunes of Star Trek as though it's solely an interaction between the writers and the fans. And supposedly the fans are granted the ultimate agency because they either accept the material or reject it. The writers are trying their best and it takes a lot for the fans to admit that maybe the writers made a mistake.

But the corporate overlords who are actually determining the broad outlines of this are never present in these discussions. They're never considered, and for instance, Enterprise, when it was meant to be the tentpole of the network, it was also constantly preempted. Its time slot was moving around constantly, and you can't do that in linear TV—people either get into the habit or they don't, and they were actively trying to make that impossible. And then they blame it on the fans for being snobs or the writing being poor. And both of those things might be true, but they're not the ultimate explanation.

Danny Sullivan: Your book made me think Star Trek has gotten imaginatively hemmed in, where every new production is either somehow related to The Original Series era or the Next Generation era, and it seems like Discovery jetting off to the far future is the one attempt the franchise has made to actually go somewhere new. And I haven't seen it, but I get the impression that didn't work out very well. Why do you think it's so hard to just set a show 200 years in the future and, while not jettisoning canon, just do something new?

Adam Kotsko: It fits with the broader trend that everything needs to be a proven intellectual property. And even though the Star Trek concept is potentially broader, the two big moments of success were The Original Series, which is so iconic, and then Next Generation, which was, in the grand scheme of things, the only truly successful Star Trek show, the only one that reached escape velocity and regular people were watching it regularly. So they are hemmed in and they're painting themselves into this corner where all the different shows fit into this 10 year period, and they're all intricately placed within each other.

It's kind of nuts, but it’s part of a broader trend: if you own an intellectual property, you have to maximize that familiarity. You have to monetize people's nostalgia. This is not only within Star Trek, of course, you see it with all the comic book movies and with all the reboots of everything. This is a way in which Star Trek, which is supposed to be about the future and exploration just winds up obsessed with its own past.

Danny Sullivan: I thought the most fascinating chapter in the book was the chapter on the novelverse. You talk about different writers who take different approaches to working within canon while writing something new or simply justifying canon. But the novelverse had to self-destruct when they made these new shows. That leaves this incredible wealth of material in this sort of canonical limbo. Star Wars has the same thing now with with its own novels, too. You point out that the idea of canon has its origins in religion and so I thought it was funny that we've looped all the way around to having apocrypha in pop culture media.

Adam Kotsko: The novelverse chapter is the one that I'm most proud of, and it's my biggest innovation as a scholar. There has been one other essay collection about the novels, but I think that my chapter is the most thorough consideration of the novelverse. In both the cases of Star Wars and Star Trek, they were long running projects that had a huge amount of fan investment, and they were swept aside or devalued for the sake of products that were not worth it, that simply were not worth it. These companies have this rich amount of stories and lore that they could draw on. They could run series for decades that are just televising the novels. The writing's already done. You've got the rights. You could just do it, and I don't know why they don't. There's never been a direct adaptation of a novel into a show. They lift plot points, but you can never graduate to that level. Apocrypha stays apocrypha, which I think is a way of policing what's canon so that the audience never gets confused about what really counts.

Danny Sullivan: The other thing interesting aspect of the novelverse was the way it establishes stuff about Star Trek lore that not only extends into the past, but into the future as well. Janeway's ultimate fate is not in the show, for instance. It's in some of these novels. So if you read those books, you have this sort of esoteric knowledge, not only of lore that we would think of generally as being in the past, but also into the future. I thought that was something that might be unique to Star Trek.

Adam Kotsko: Lore like that is a resource. It's something you can draw on selectively. The novels do form lore for the writers of the shows. They can choose certain concepts and elevate them to canon, but they don't have to. They could selectively dip back into the archives and say, “Oh, there's this thing we forgot about,” or “Here's this weird event that happened, and we can leverage that for a new story.” And I think that's very productive and a cool benefit of having a long-running tradition of storytelling. But the corporations make it into a straitjacket themselves.

We should not forget that canon is a marketing strategy to put everybody on the hook continually. If you want to know what happened in Star Trek, you need to watch every single show because every one is canon. Again, we need to focus on the way that the corporate ownership structure has distorted these things, has turned lore into canon in ways that then they turn around and complain about and blame the fans for what they themselves chose to do.

Danny Sullivan: You also have a newsletter about Star Trek, where you’ve been expanding on the book and revisiting the more beloved shows. Two of my favorite articles you’ve done there were your reading of the classic DS9 episode “In The Pale Moonlight” as a riff on Faust and another about Worf that you related to The Odyssey. You are showing how we can read Star Trek in more interesting ways, and I wonder if the default to canon and lore is where you end up if you don't have those classical references to draw on, or if you just don't quite know how to make that imaginative leap?

Adam Kotsko: I have a privileged position as a trained academic in the humanities, obviously I'm going to make more of those connections than the average person, but most people have done high school English. They know how to interpret a story and notice symbolism and so on. I found in my discussions with fans that they resisted the idea that there was symbolism or that there were themes discussed, or even that there were patterns or that there was intentional structure to things. They want it to be a newspaper from a fictional universe. They don't want it to be a story. They want it to be factual. That is easier in a way, but I think that the construct of canon encourages people to think that way. And the fact that things can be referenced simply for the sake of referencing and not for an organic reason—why does Captain Picard need to be the one to discover this fact about how all humanoids are related? Why is that this week's adventure? Why does everything happen to them? These questions are not asked. They want to forget that it's fiction, and I think part of that is a kind of intellectual laziness. But it’s also the distorted incentives that the idea of canon gives them—that they're rewarded for their memorization of facts from the canon, but they don't get the same type of rewards for actually understanding how the stories work or why we care.

Danny Sullivan: You make the point in the book that TNG is very much a product of its time in its late 80s/early 90s unexamined triumphalism, that there's a sense we're in Francis Fukuyama’s end of history thesis. And perhaps it felt plausible that this post-scarcity, non-ideological future is where we were headed. But, of course, history has taken a bit of a turn. How do we read Star Trek's imaginative world in our current moment of punitive neoliberalism and outright authoritarianism?

Adam Kotsko: I think Star Trek has always echoed its time. People come to Star Trek sometimes for a more critical viewpoint, and I think the science fiction framing lets them do that. But at heart it's responding to and echoing the broader culture. So you're right about Next Generation fitting perfectly with happy 90s neoliberalism and maybe Deep Space Nine is starting to realize things aren't quite so simple. Voyager wishes they could get back home, but they seemingly never can.

The newer stuff does still try to have this critical edge to it. I think that in Discovery season one, they thought they were saying something about nationalism and militarism and authoritarianism, but that message wound up being kind of garbled by the complexity of the plot. And similarly, I think that Picard tries to comment—in season two they go back to our present day and they show immigration raids and things like that. So there's a desire to be critical, but it still fits with a kind of broadly capitalistic, self-expressive individualism—the fact that politics are never explicitly shown, we're never told how this transition to a post-scarcity environment occurred. And they're willing to compromise the post-scarcity environment very frequently. Like Picard lives in a mansion and his former first officer lives in a shack. So it's kind of incoherent in the way that every commercial product is incoherent.

Danny Sullivan: The other part of Star Trek that is interesting to look at now is the show's relationship to technology. The Original Series was made at the height of the space race and The Next Generation comes at the beginning of the personal computer revolution. The vision of technology in these shows is very practical and utopian as well, and it feels more depressing by the day to look at our technology in the real world and see how it's all built on systems of profit and attention capture and so on.

Adam Kotsko: Yeah, the one technology they interrogate somewhat is the holodeck because with their radically self-actualizing lifestyles there's something implausible about the fact that they find the holodeck fun. It's impossible to believe somebody as smart as Captain Picard would find it engaging at all. What ruined those episodes for me permanently was the advent of AI in our world, which is so hokey and crappy and inaccurate, and realizing that they're portraying our hyper-intelligent characters as engaging with basically a very advanced ChatGPT-based entertainment system.

What's really interesting is in Deep Space Nine, the holodecks are run by Quark, who's a Ferengi, who therefore has a profit motive. They finally come out and say what we all knew, which is that Holodecks are for porn. They admit it's for profit.

Danny Sullivan: Speaking of AI, it sounds like we're broadly on the same page. I find it disgusting and appalling, and I find it bizarre that people are excited to talk to ChatGPT. Reading your book Neoliberalism's Demons, I started to see AI as the latest salvo from the forces of neoliberalism to further devalue both our labor and our lived experiences. Do you agree with that? Do you see Silicon Valley as a foot soldier of the neoliberal project?

Adam Kotsko: One element of neoliberalism that I highlight in the book is that it's structured around a bunch of forced choices in which we're given a very, very narrow range of options, many of which, or sometimes all of which, are undesirable. We pick one and we're blamed for the outcome as though we had full agency to choose the entire situation. We're given enough agency to be blameworthy but not enough agency to actually do anything effectively. And I think that algorithmic social media does the same thing. It was always presenting us with slop. I get served the stupidest stuff on Facebook, and if you don't actively cultivate and manage it, it concludes that you must like it and gives you more.

That’s always the alibi: it's giving you what you want, it's giving you what you chose. Similarly, the promise of AI is an even greater customization of your experience, that it's only going to give you stuff that's relevant to you. But the mechanisms by which we're able to say what's relevant to us are very narrow and proscribed by the fact that we don't get to choose what the options are in the first place. With a lot of online radicalization, for instance, yes, the people did choose to waste their time online and get down these destructive rabbit holes, but the software is designed to be addictive. It's incentivized to get people into more and more simplistic and predictable spaces. Radicalization happens because once you're in that space, you always are going to be served more of it. And yet it's all the individual's fault.

That's what bothers me about it. It's always, “They should have known better.” Yes, they should have known better, but you should have known better than to put them in that situation in the first place. You should have known better than to drop them into the casino and turn them into a gambling addict. So my worry with AI is that it's going to get to a point where in many settings, all we’ll be offered is AI slop, and we'll be forced to choose between it, and they'll say it's what we wanted because we indicated a preference in some way within this limited range of options.

That same critique of forced choice is present subterraneously in Late Star Trek in my argument that fans are not to blame for how Star Trek is. They have the least agency over what it's like. They have no agency over what it's like. They do not make decisions, they're not in power, and writers have more obviously, but the people who provide the money have the most. Agency and responsibility are always inverted. The person with the least ability to do something, the blame is piled on them. And the people who actually control the situation, it's as though they're simply pass throughs for the market, which is supposed to be just a pass through for our desire.