In January 1955, William Gaddis wrote Robert Oppenheimer a letter. Gaddis was 32 and was weeks away from the release of his first novel, The Recognitions. The book, nearly 1,000 pages long, is an unparalleled debut. Dense with classical allusion, it concerns art forgery, authenticity, the self, and the breakdown of meaning, coherence, and categorical thought. There’s a 70-page party scene.

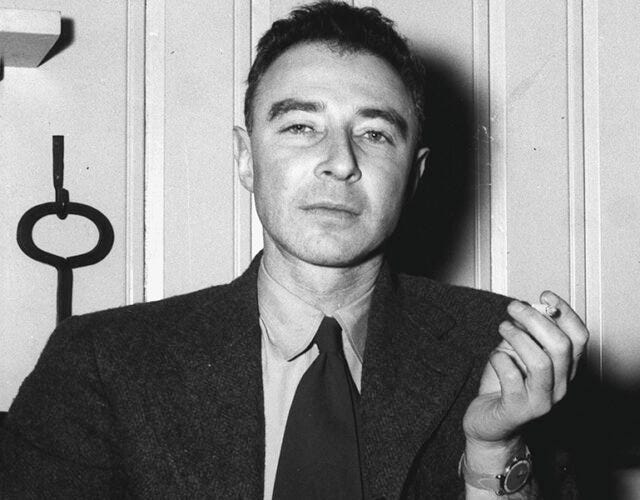

Gaddis wrote to Oppenheimer to call attention to the copy of The Recognitions he had asked his publisher to send him, remarking “You must receive mail of all sorts, crank notes and fan letters of every description, but few I should think of half a million words.” Gaddis was compelled to do so because he had read the lecture Oppenheimer delivered at Columbia’s bicentennial celebrations a week before. In his first public appearance since being stripped of his security clearance for his supposed Communist sympathies in June 1954, he delivered the closing lecture of the series, the theme of which was “Man's Right to Knowledge and the Free Use Thereof.”

More specifically, Gaddis found great congruity between his thinking and Oppenheimer’s: “I was so stricken by the succinctness, and the use of the language, with which you stated the problems which it as taken me seven years to assemble and almost a thousand pages to present, that my first thought was to send you a copy.”

In his talk, titled “Prospects in the Arts and Sciences,” Oppenheimer did not strike an optimistic tone. He imagines the state of the arts and sciences as a planet and the various disciplines and subject areas as villages. Surveyed from above, by rocket, one could look down on the total situation of both, which share a kinship despite their superficial differences. That view, on first pass, would show much to be glad about—the number of people engaged in scientific inquiry had never been higher, the great music of the past never more accessible. But look a little more closely and worrisome elements begin to emerge:

This great map, world-wide, culture-wide, remote, has some odd features. There are innumerable villages. Between the villages there appear to be almost no paths discernible from this high altitude. Here and there passing near a village, sometimes through its heart, there will be a superhighway, along which windy traffic moves at enormous speed. The superhighways seem to have little connection with villages, starting anywhere, ending anywhere, and sometimes appearing almost by design to disrupt the quiet of the village. This view gives us no sense of order or of unity. To find these we must visit the villages, the quiet, busy places, the laboratories and studies and studios. We must see the paths that are barely discernible; we must understand the superhighways, and their dangers.

That is, intercourse between disciplines is nearly non-existent. Subjects have become increasingly insular, with specialized vocabularies and modes of thought that are increasingly incomprehensible to those outside them. This is true, in Oppenheimer’s view, of both science and art and especially across the great divide between the two. Physicists can’t talk to chemists, chemists can’t talk to poets, and poets can’t talk to painters.

We can begin to see why Gaddis responded to this talk. The questions he grappled with for seven years composing The Recognitions are of exactly this sort. Wyatt, the central character, is a painter who cannot create original paintings and instead forges lost works of the great masters. His identity becomes so effaced that Gaddis refuses to use his name for probably 400 pages in the middle section of the novel. He ends up in Spain silently scraping away paint from Goya canvases, unable to explain why. Otto, dealing with a different sort of identity crisis, is caught up in mirrors and fails to recognize his own father when they meet, who also fails to recognize him; his name is both a palindrome (mirroring) and a pun on the Greek αὐτός, meaning self. Stanley, a composer, can’t complete his masterwork. The problem of recognition and, further, the inability to bridge the gulfs between ourselves and others to establish true communication, would be the fundamental theme of Gaddis’ whole career, to the point that his next novel—JR—would be 700 pages of almost pure dialogue, in which it’s questionable if anyone is ever understood.

Instead of human-level communication between scientists and artists—the paths between villages—there are the superhighways:

They are the mass media… purveyors of art and science and culture for the millions upon millions—the promoters who represent the arts and sciences to humanity and who represent humanity to the arts and sciences; they are the means by which we are reminded of the famine in remote places or of war or trouble or change; they are the means by which this great earth and its peoples have become one to one another, the means by which the news of discovery or honor and the stories and songs of today travel and resound throughout the world. But they are also the means by which the true human community, the man knowing man, the neighbor understanding neighbor, the school boy learning a poem, the woman dancing, the individual curiosity, the individual sense of beauty are being blown dry and issueless, the means by which the passivity of the disengaged spectator presents to the man of art and science the bleak face of inhumanity.

This idea—that mass media was deforming the social fabric of the country and impoverishing our experience of life—is so far ahead of its time. It’s startling to see it put so clearly. “The individual sense of beauty being blown dry and issueless,” the texture of existence, our aesthetic sensibility as fragile as tissue paper. He’s forty years ahead of Bowling Alone and sees clearly the devastating effects on our attention and sensitivity caused by the internet.

Oppenheimer’s examples of small moments of life fully lived—the school boy learning a poem, a woman dancing—are so moving to me. He captures an important sense of being alone, focused but spontaneous, working mentally, experiencing one’s own mind and body, and finding that experience of being alive stimulating and delightful. It is precisely what bifurcated attention, addiction to novelty, and thousands of tweets rattling around your brain cut you off from. It’s a fitting coincidence that the original epithet of the internet was “the information superhighway.”

There is a tremendous amount at stake in the question of interdisciplinarianism, of the cross-pollination of the scientific and artistic disciplines. Oppenheimer himself is a perfect example. Besides building the bomb and three nominations for the Nobel prize, he was also deeply interested in the classics, mysticism, and the Hindu scriptures specifically. His quotation from the Bhagavad Gita on seeing the Trinity test is famous but it’s less known that his interest in those texts went so deep that he learned Sanskrit and read the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads in their original language. The conventional rendering of what Vishnu says is “Now I am become Death, shatterer of worlds”—Oppenheimer recites it as “destroyer of worlds” because he’s drawing from his own translation.

Did these readings help him in his scientific pursuits? It’s hard to say. What is clear, however, is the role his immersion in philosophy and mythology played in grappling with the consequences of his actions. That clip is so haunting because of how haunted Oppenheimer is. He has borne the weight of the dead of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for twenty years and watched his invention deform international affairs and usher in an unprecedented age of secrecy and suspicion. Like the prince, he did his duty.

What’s the last example of anything this humane and humble—someone genuinely struggling with the enormity of history and their place in it? Willy Brandt kneeling at the Warsaw Ghetto memorial in 1970, maybe? It’s impossible to imagine a fossil fuel executive ever taking responsibility for the profound violence they have done to the world and the future. Insulated by money and their own blithe thoughtlessness—Oppenheimer’s “bleak face of inhumanity”—they will never give us an ounce of contrition, one scrap of atonement for what they’ve stolen from all of us.

In this vast, windy world, the scientists get little love from the general public. Their work is too remote to be accessible, except as it trickles down as technology. Not least of which, the pinnacle of scientific endeavor to that point, was manifested in atomic horror. But the scientist can at least find comfort in the company of peers, who understand the work and the goals. For the artist the situation is far worse:

For the artist it is not enough that he communicate with others who are expert in his own art. Their fellowship, their understanding, and their appreciation may encourage him; but that is not the end of his work, nor its nature. The artist depends on a common sensibility and culture, on a common meaning of symbols, on a community of experience and common ways of describing and interpreting it. He need not write for everyone or paint or play for everyone. But his audience must be man; it must be man, and not a specialized set of experts among his fellows. Today that is very difficult. Often the artist has an aching sense of great loneliness, for the community to which he addresses himself is largely not there; the traditions and the culture, the symbols and the history, the myths and the common experience, which it is his function to illuminate, to harmonize, and to portray, have been dissolved in a changing world.

Again, it’s shocking to encounter someone saying the audience for high culture has disappeared in the 50s. To take film as an example, the conventional story is always about the flourishing of New Hollywood in the 60s and 70s—that there was a robust audience of engaged thoughtful adults whose attention allowed the industry to create mass-appeal fare that was thoughtful, slow, and rewarded attentive viewing—which dried up which the age of the post-Star Wars blockbuster and the general cultural doldrums of the 80s.

Why is the proper audience for the artist “largely not there?” Oppenheimer provides a vague answer with his assertion that “the traditions and culture…have been dissolved in a changing world.” I’m frankly not sure what this means. It seems as if he’s saying that artistic output is not equal to the times, not able to synthesize the upheaval in society. I’m not sure I buy it. More likely is the prospect that audiences have disengaged, that forces in their lives have crowded out the time or sensitivity to appreciate and prioritize the aesthetic. Since time immemorial people have understood that taste has to be cultivated—virtue taught—and diverse mechanisms were invented to do so. At some point in America we simply stopped bothering with these efforts, just as a classical education went from the norm to a bizarre niche. Have the symbols and myths been dissolved by the changing world or are they unknown to the audience in the first place?

Oppenheimer continues:

To the artist's loneliness there is a complementary great and terrible barrenness in the lives of men. They are deprived of the illumination, the light and tenderness and insight of an intelligible interpretation, in contemporary terms, of the sorrows and wonders and gaieties and follies of man's life. This may be in part offset, and is, by the great growth of technical means for making the art of the past available. But these provide a record of past intimacies between art and life; even when they are applied to the writing and painting and composing of the day, they do not bridge the gulf between a society, too vast and too disordered, and the artist trying to give meaning and beauty to its parts.

This should have been the part of the talk that scared Gaddis the most. The Recognitions was snubbed by critics and the public on release. Gaddis was stunned and carried that bitterness with him for the rest of his life.

“The terrible barrenness in the lives of men” is one of the great problems of our age and one that has only gotten worse in the nearly 70 years since Oppenheimer delivered this lecture. The transformation of higher education into vocational training seems to have largely stamped out that connection to a common well-spring of humanity that Oppenheimer pinpoints as essential. Need I invoke the word neoliberalism or the phrase “late capitalism?” We are set adrift with no help and no sustenance, either material or spiritual. The consequences of this state of affairs are too obvious to bear mentioning.

Oppenheimer’s worries came true—efforts for a more open, vulnerable society were foreclosed across the board. Against the myriad forces set against us, we can only work to keep an open mind, to cultivate our higher sensibilities. It is essential and virtuous work; it is our duty.