This post is image-heavy and will probably get cut off as an email. I suggest clicking on the headline to read it in browser instead.

Every Wednesday I drive to my old college campus to do a lunchtime film seminar with two of my old tutors professors. With a couple other exceptions, the rest of the group—there’s usually 10-12 of us—are current undergrads. I try not to talk excessively about my alma mater because who gives a shit but I need to mention that St. John’s is the Great Books Discussion School, so our approach to talking about these movies is modeled on how we talk about the texts of the regular Program. That is to say, it’s all very by the book—if someone in class makes what you think is an unsupportable assertion, the standard rejoinder is to ask them, “Can you point to that in the text?”.

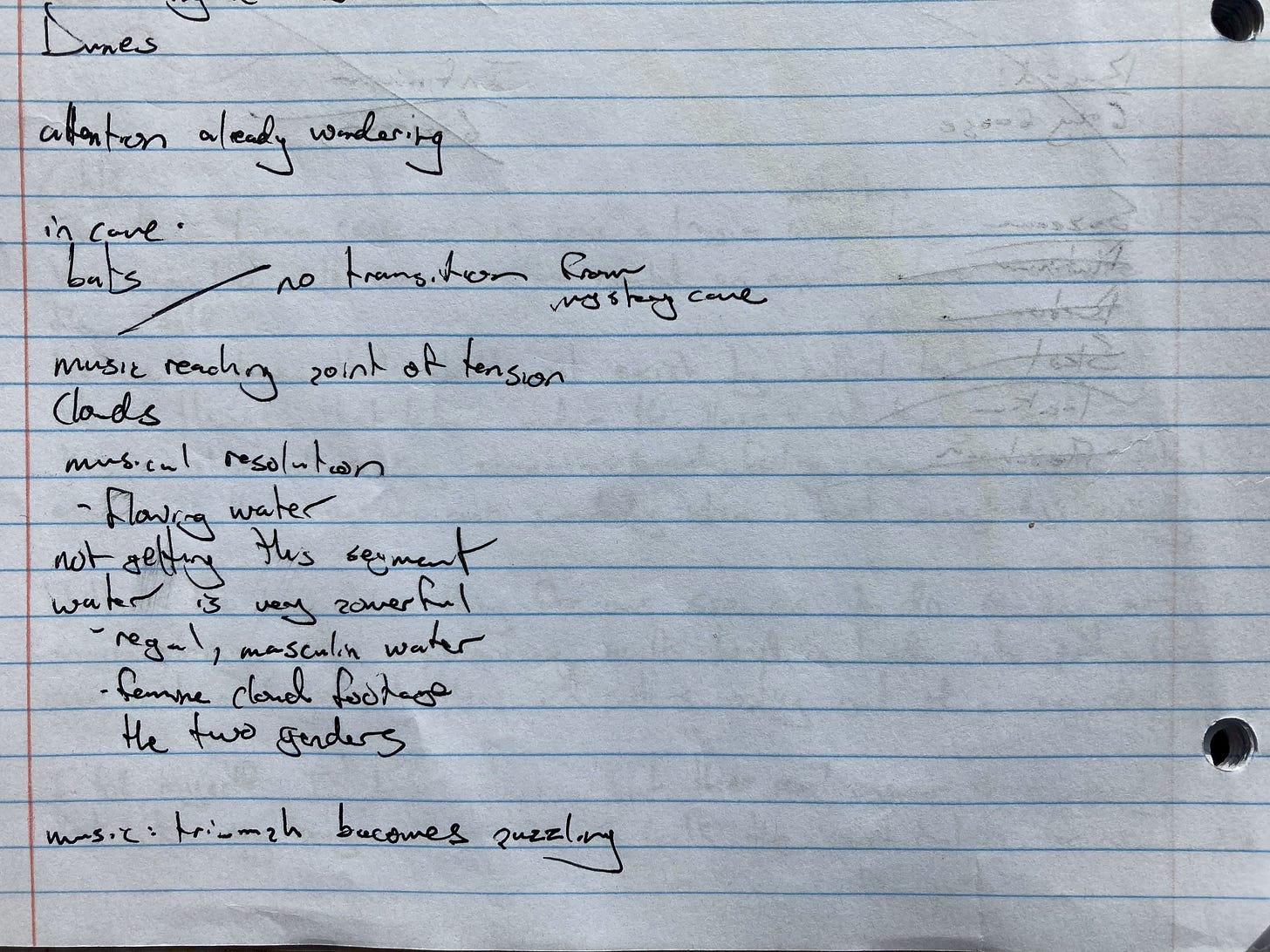

But film is, inconveniently, not the written word. Since I love a juicy quote and need to base my claims in evidence like a fish needs water, I take extensive notes while I watch these movies. They usually consist of a mix of tracking basic plot, significant lines of dialogue, and anything the movie is making me think of that I want to remember later. It may sound like I’m distracted and barely watching the film but, counterintuitively perhaps, this constant scribbling is precisely how I pay attention on a deep level.

One film pushed my notetaking to new extremes: Koyaanisqatsi. Directed by Godfrey Reggio and released in 1982, it’s famed as “the documentary with no narration.” I previously thought of it primarily as a stunt film, often referenced by college-aged film buff poseurs in the same breath as Russian Ark (It’s all one take, bro!) and Memento (It plays backwards, bro!). With nothing but a Philip Glass score, it’s generally described as a love letter to Mother Nature and man’s place within nature.

That is, to put it lightly, not my reading of the film. We’ll work through the specifics as we go but I’ll say this up front: I think this film should be locked in a vault with The Birth of a Nation and Triumph of the Will and only shown in controlled educational environments to illustrate how skillful filmmaking technique can be used to genuinely evil ends.

Now that being said, there’s a level on which this movie is really fun to watch. Wait, stay with me! Because Koyaanisqatsi has no words and is nothing but one long montage, watching it is an exercise in Pure Cinema. It is essentially one massive example of the Kuleshov Effect, the famed demonstration that audiences will read the same facial expression as different emotions based on the images surrounding it. Koyaanisqatsi is the Kuleshov Effect turned into a snowball, each new image rolling up into the mass of all that have come before and adding to the accrued context in which each further image will be read. To watch the film closely is to enter a free associative state in which each image is a metaphor and there are no wrong answers.

So I thought it would be fun to go through my notes from my first viewing and watch as I start to develop a reading of it and grow more and more incensed. Let’s begin!

The film immediately announces that it will be about juxtaposition. The Egyptian Book of the Dead figures are concrete, immediately recognizable; the rocket footage is a close-up of the bottom section where the flame emerges and plays in ultra slow-mo, making it so abstract as to be at first indecipherable. Reggio is setting up a series of confrontations: ancient vs modern, indigenous vs western maybe, tangible vs abstract.

Similarly in the following landscapes. Monument Valley is iconic but that’s a trick of photography—pan away and there’s nothing but flat scrub land. Is America the monuments or the plain?

More nature footage. Not a ton happening but it’s pretty. I’m starting to get to the associative level the movie wants me at as I start to assign gender dynamics to ocean water and clouds.

Our first section change. Machinery enters the picture. Pristine nature is being despoiled by industry. Pollution is rampant. Everything in nature is one of a kind but people build identical structures, which are unsettling.

I’m with the movie so far. Nature is nice and it’s sad to see it destroyed.

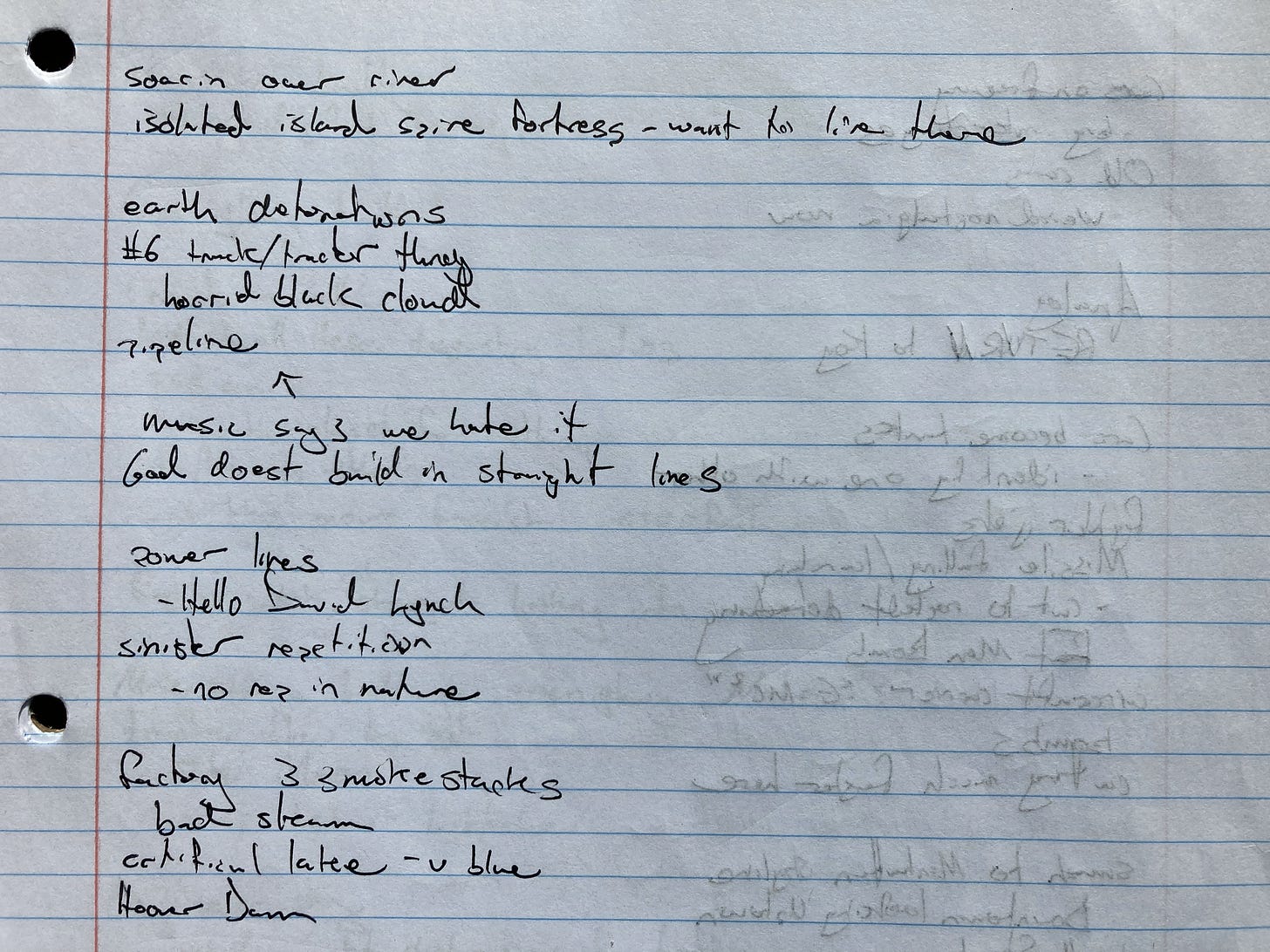

Hmm the message is starting to get a little mushy. It seems wrong to conflate the Hoover Dam with the belching smokestacks of a chemical plant. The Hoover Dam supplies a lot of clean electricity—are we so sentimental that we can’t accept that tradeoff?

We’re supposed to be horrified by beachgoers frolicking in the shadow of nuclear reactors but why? We’re getting our first hints that this movie may have a misanthropic streak. This footage clearly says, Look at these ignorant fools, blind to the horror right in front of their eyes. But I see no reason to be so harsh—if we trust that no contamination is occurring, why the automatic revulsion against nuclear power? There’s an assumption baked into this image that begins to tip the movie’s hand, showing its perspective to be reactionary and uncompromising.

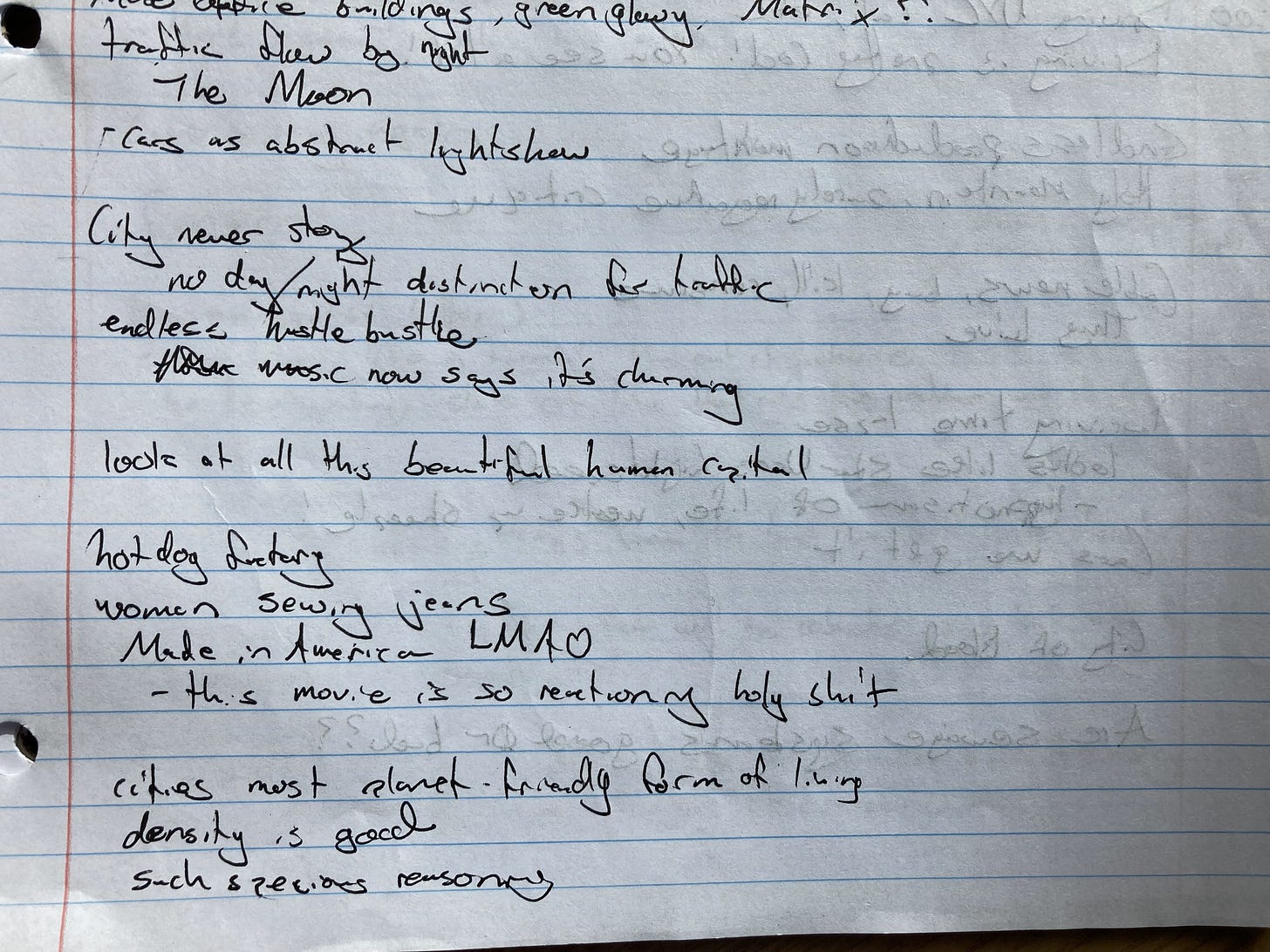

Because this movie focuses on technology and is also 40 years old now, it has a weird relationship with nostalgia. This footage of old cars is supposed to gross us out—look at all these people clogging the freeway—but they have so much more personality than modern cars and they have no screens or other digital nonsense added in. Doesn’t seem so bad! We might suspect Reggio would prefer more eco-friendly forms of mass transit but we’ll see in a bit he hates that too.

When the cars transform into tanks, clearly we’re making a point about the military-industrial complex. All that domestic spending funnels back into building bombs to drop overseas. No argument here!

Another section change. Here’s where the film gets really problematic. After establishing that this is New York by showing us footage of Wall Street (Manhattan, where white people live), we go across the river to gawk at black people loitering on the sidewalks in Brooklyn. It immediately called to mind the Broken Windows theory of crime, the disproven and racist policy that sought to prevent major crime through draconian enforcement against minor crime. I could hardly log the thought before Reggio went into a long montage of literal broken windows footage. Not only does he have a sentimental attachment to nature, he also has a sentimental attachment to buildings. He shows old buildings being demolished and we’re supposed to think that’s so sad, so wasteful. But again, that’s just sentimentality detached from any sort of reason; buildings need to be destroyed sometimes, they’re probably full of asbestos, that’s life.

At this point, the film’s argument seems to be People have mutilated the earth with their stupid need for food and shelter and these savages can’t even be bothered to keep their precious buildings in good condition. It’s really gross but also a fundamentally shallow critique. Rather than interrogating the policies and structures that have led to this sort of urban neglect the camera just focuses pornographically on its most lurid symptoms.

Up to this point the film has focused much more on mankind’s creations than mankind itself. Now Reggio needs to make it clear that he hates human beings not for their works but as human beings specifically. This part contains a sequence of people on the street in New York City streaming past the camera, which is placed low and tilted down to cut off at the neck and keep their faces out of frame. All we see are fat bellies and bad posture and sagging flesh. Reggio finds human beings disgusting and interchangeable. He wonders why we would desecrate the planet to sustain these horrid sacks of meat.

At this point I realize I’m watching fascist cinema.

Now Koyaanisqatsi lapses into the endless hustle-bustle of sped up footage of commuters packing the escalators out of the subway, cars driving down Manhattan avenues and stopping at every light, and other signifiers that all add up to the idea these people do nothing but work, they have no fulfillment, no inner lives, all this frantic activity is for nothing except to sustain itself. I find it so insulting, and not just because I was one of those NYC subway commuters for five years. When I cited this section in the group discussion as an example of how hateful and misanthropic I think the film is, its most ardent defender shot back that this is how life is and I just can’t accept it because I’m the sentimental one (for believing that people are unique and have inner lives, I guess). But, like, this isn’t how life is! The film contains no footage of domestic life, of leisure, of anything pleasurable. Those things exist! I read Wuthering Heights on the train in to work! Life sure does look grim when you only include drudgery and exhaustion but that’s not an honest portrayal.

But then even within this relentless critique of industry, he lovingly shoots the Made In America patch on the jeans. An eco-fascist? Who’s also a nationalist? You don’t say…

As we approach the one-hour mark, we finally see some people having fun. Unfortunately, Reggio still hates it. In the arcade young people are twitching and reacting hyperactively to the screen. In the movie theater the crowd sits entranced, mouths agape, hypnotized and thoughtless. There’s no pleasing this guy. Confronted with the sight of people at rest, doing what they please, he recoils, No, not like that!!

And then, look at these crowds in the grocery store. Look at these fat hogs buying their slop. Like, yeah man, going to the grocery store sucks but I need to buy food. What’s the alternative, moving to the wilderness and subsistence farming lichen?

I’m getting angry at this point. Because he’s repeating himself with more stupid footage of cars driving, Reggio has given me a moment to think through some of the implications of his anti-modernist, anti-technology, anti-society message. Is modern medicine a good thing? Is modern sewage treatment a good thing? Would we prefer there was cholera in the water? Well…

We’re nearing the end. Koyaanisqatsi now pivots into some vile footage of people injured, bleeding, lying on a gurney with filthy bandages. The camera is fetishistic and immoral. In the context of all that’s preceded it, I can only take this section to be saying And ultimately, it’s nothing but suffering. We rape and pillage the earth and it’s all for the sake of pain. It would be better if these people had never been born. I thought of Rust Cohle’s speech from the first episode of True Detective:

I think human consciousness was a tragic misstep in evolution. We became too self-aware; nature created an aspect of nature separate from itself. We are creatures that should not exist by natural law. We are things that labor under the illusion of having a self—this accretion of sensory experience and feeling, programmed with total assurance that we are each somebody, when in fact everybody’s nobody… I think the honorable thing for our species to do is deny our programming, stop reproducing, walk hand in hand into extinction, one last midnight, brothers and sisters opting out of a raw deal.

There it is. That’s the movie. Koyaanisqatsi is anti-natalist, pro-extinction cinema. It doesn’t contemplate the means that would be necessary to achieve that goal, but it’s not hard to imagine. This is an evil film.

And then we end with a little cultural appropriation for good measure.

I feel obligated on behalf of humanity to say that human consciousness was not a tragic misstep. It is literally all we have, the greatest miracle of existence, something beautiful that is to be treasured above all else. Innumerable philosophies and religions have been born from the attempt to make sense of the wonderous fact of our working minds. Hoping for it to be extinguished not only goes against everything I stand for but is essentially incomprehensible to me as a proposition. To wish for humanity’s extinction for the sake of preserving nature is to make a value judgment—but it’s only our consciousness that makes value judgments real. A world without people might include a pristine planet Earth but it would be without value.

Fascinating take and while I don't remember the details of the film all that well, as I watched it in cinema in mid 1980s and not again in full after that, it does seem to capture the VIBE well.

To the assesment of "Koyaanisqatsi is anti-natalist, pro-extinction cinema." I'd also add that it feels like this antinatalism really (not explicitly but it's there if you look) extends to non human life too. That also is depicted with at least some repulsion if not outright disgust. The only unequivocally beautiful images the author clearly approves of are inanimate landscapes, or ones which are far enough from the eye that they feel so: perhaps it's made by an alien robot/non carbon based life form disgusted by the squelchy, dirty violence of life on Earth.