Joe Biden has speedrun his way to lame-duck status in record time, though the credit goes mostly to Joe Manchin. The West Virginia senator has for a full year now moved the goalposts and negotiated in bad faith against his own party to water down and ultimately thwart every aspect of Biden’s domestic agenda. His reasons for opposing the infrastructure and Build Back Better bills have shifted as different pieces of the legislation have taken focus, including a full rejection of anything that might threaten the fossil fuel industry (for obvious reasons), as well as demanding work requirements to receive the benefits of any new spending for families and health to avoid “changing our whole society to an entitlement mentality.”

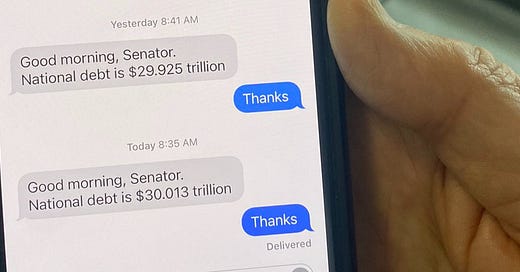

Above all, though, the numbers have just been too big. 3.5 trillion dollars was too much spending, then 2 trillion was as well, then 1.75. This incredible fear of the cost of improving society somewhat seems to stem from Manchin’s worries over the size of the national debt. NBC News recently reported that a staffer texts him the current national debt every morning, a figure that recently surpassed $30 trillion and that seems to occupy a central place in his mind. “$30 trillion should scare the bejesus out of your generation,” he told NBC.

Manchin is afraid of the national debt because he doesn’t understand it and he doesn’t understand America. He doesn’t understand that the United States is an empire and empires, unlike mere nations, can never be in debt.

Just for the sake of thoroughness, let’s check the boxes. Empires, generally speaking, are defined by sustained military action that continually expands their territory, or at least their influence. Between the U.S.’s global network of military bases, the last twenty years of endless war, drone bombings that operate largely without oversight, and its penchant for violently imposing our preferred system of government, we have this one covered. Late stage empire also manifests as domestic rot, as petty proxy battles between polarized factions distract from the basic work of sustaining a functioning society. I won’t belabor this point further!

A third, key point for our purposes, that David Graeber points out in Debt: The First 5,000 Years, is the payment of tribute by vassal states back to the central imperial power. Pericles’ Athens operated on this model, for instance. A quick cruise back through Thucydides is enough to remind us that Athens had colonized much of the perimeter of the Aegean and the tribute paid to the city by the conquered territories both funded its flourishing culture and directly precipitated the Peloponnesian War.

This seemingly complicates the tidy picture of the U.S. as an empire because on the face of it we do not exact tribute. Of course we actually do, as Graeber explains in depth.

To return to Debt, Graeber hammers the point throughout the book that the entire history of human economic activity is inextricably linked to violence—chiefly war and slavery. This remained true through the last major development in this history: Nixon abandoning the gold standard and “floating” the dollar, a move necessitated by the cost of the Vietnam War. Instead of turning our money into worthless paper, this miraculously turned the dollar into the entire world’s “reserve currency,” the bedrock of the global financial apparatus. Conversely though, foreign banks had little they could actually do with their dollars except buy U.S. Treasury bonds. The money spent on these bonds flowed back to America and fueled the prosperity the Baby Boomers enjoyed for decades.

Treasury bonds, in theory anyway, mature, at which point the buyer can cash out, making some sort of profit based on economic growth since they were purchased. I’m a little fuzzy on this part—whatever, as we’ll see, it doesn’t matter because it’s not true. Since bonds are, in the long run, supposed to be paid back, they are considered a form of national debt in common thinking. This is the doomsday that supposedly haunts our principled deficit hawks in Congress: when China comes calling with its wad of mature Treasury bonds, how will we pay?

In fact, we won’t, ever. Graeber cites Michael Hudson, an economist who in the 70s realized that America’s indebted status had become too essential to the global economy ever to be undone. (This follows from historical examples presented earlier in Debt that establish that essentially all monetary systems originate in circulating promissory notes from the crown, or in other words “monetizing” national debt.) “To the extent that these Treasury IOUs are being built into the world’s monetary base,” Graeber quotes Hudson as writing, “they will not have to be repaid, but are to be rolled over indefinitely. This feature is the essence of America’s free financial ride, a tax imposed at the entire globe’s expense.”

But it’s actually more pernicious, Graeber elaborates: “What’s more, over time, the combined effect of low interest payments and inflation is that these bonds actually depreciate in value—adding to the tax effect, or, as I prefer to put it, ‘tribute.’ The effect is that American imperial power is based on a debt that will never—can never—be repaid. Its national debt has become a promise, not just to its own people, but to the nations of the entire world, that everyone knows will not be kept.” It’s worth noting that, though this argument centers on Treasury bonds, it now encompasses the entire national debt, no part of which will be repaid.

At the risk of saying something nice about a man I despise, who is willing to sell out the planet and the human race for his oil money, I think Manchin’s worries about the national debt are genuine. I think he really does worry about a doomsday scenario when the debt matures and the country is caught flat broke. But it also betrays his eighth-grade civics class understanding of the issue. None of it is real! The deficit does not exist because the deficit must exist. It cannot be paid down and only goes up on paper. The growth of the national debt is the entire engine of the economy; it pays for everything we do. The only difference between the U.S. and Athens (actually there are a few) is that the U.S. perversely insists on counting up the amount of tribute we’ve collected, taunting our vassals with the laughable suggestion that we’ll get them back eventually, like when my buddies spotted me beer in college.

It’s hardly surprising, if dispiriting, to have the barest minimum of progress blocked by a completely imaginary problem while disasters pile up around it. Unfortunately we, unlike Joe, have to live in the real world.