Small life update: We’re in Santa Fe! It’s been a very long month, moving across the country and getting settled in our new place. I guess there isn’t much else interesting to say but I’m excited to have a more regular schedule again and get back to publishing a little more frequently. Thanks for bearing with me everyone! Here’s a picture of the sky I took while I was walking back from the library with Patrick.

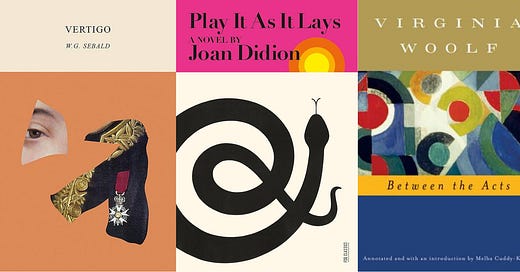

Vertigo, W. G. Sebald, 1990

My former professor (and subscriber, hi Natalie!) recommended Sebald to me. That was enough to get me to pick up his first fiction—though that’s a bit of a fraught descriptor—with basically no idea what I was in for, which turned out to be the perfect way to experience this disorienting meditation on history, literature, and memory.

The first in loose trilogy, the book is in four sections. The first is a biography of sorts of Stendhal, whom Sebald refers to exclusively by his real name—Henri Beyle—while assiduously avoiding referencing The Red and the Black or The Charterhouse of Parma, instead refracting the author’s romantic life through his lesser-known work On Love, it becoming increasingly unclear where verifiable biography ends and Stendhal’s self-fictionalizing begins. Though only 30 pages long, the Stendhal section sets the parameters of what follows—we’re working somehow simultaneously in the realms of the hopelessly obscure and the hopelessly overdetermined, where the web of connections between one’s inner life and outer reality is overwhelmingly dense but utterly mysterious.

Sections two and four, each around 100 pages long, are travelogues from Sebald’s perspective. Or, if you prefer, an unnamed narrator whose biography bears a strong relation to the author’s—I have no patience for these kinds of distinctions, it’s Sebald as far as I’m concerned. He is a marvelous writer, which is good because he’s mostly telling you about which trains he took as he tramps around Italy in an only semi-sane state. Taking a train to Lake Riva to follow a trip Kafka made there, he sees twin boys who look identical to him; he tries to talk to them, then their parents, eventually asking them to mail him a picture of them; at that point he realizes he’s on the verge of being arrested and returns to his seat humiliated. In Milan he has a dissociative episode in a cathedral and climbs to the roof before he regains his identity and memory of how he came to be there. In the final section he returns to the tiny village where he grew up in Germany and sifts through his childhood memories, surveying for the first time as an adult spaces and landscapes that lived in his mind still haloed by the bright sunlight of childhood.

Section three recounts the story of Kafka’s trip to take the waters at Riva. Like the Stendhal chapter, it primarily concerns an unrequited romance, in this case one Kafka had during his sojourn in Italy. The focus on romantic love stands in contrast to the parts about Sebald, who never discusses his love life or tries to spark a connection during his travels. I’m not sure what to do with this incongruity but in a book fixated on the hidden consonances between things, the lack of connection between his literary subjects and himself in this regard stands out.

This was a fitting thing to read in an AirBnb during the middle phase of our cross country move. It’s a book about inhabiting liminal spaces and where our thoughts drift to when detached from familiar surroundings. Mostly it filled me with an intense melancholy for the pre-internet world, where one’s thoughts were free to run without interruption and strangers on trains and in hotels were eager to talk.

Here’s a confession: I don’t spend much time remembering. I think about my childhood very little and don’t tend to believe in the sort of magnetic lines of force Sebald traces between things. So his way of relating to the world is quite foreign to me. I loved it—reading Vertigo was an aptly vertiginous experience, one in which I felt I was meeting another mind thrillingly different from my own. What possibilities there are.

Play It As It Lays, Joan Didion, 1970

I get the feeling that opinion on Didion has shifted pretty dramatically in the last few years, as her 60s work has gone from withering dissection of the emptiness of the counterculture to the reactionary ravings of a Goldwater die-hard. I’ve felt this shift within myself. The first time I read Slouching Toward Bethlehem I was, like every wannabe magazine writer, enthralled by her prose and the daring to foreground her own perspective. I reread the first piece from that book, “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” somewhat recently and couldn’t believe how stupid I found it—just her pointing at this woman and going “This dumb bitch thought she could have a house with a yard, she sure got what she deserved.”

Anyway, I’d never read any of her fiction and I found this at the little free store in our old neighborhood so here we are. Composed of around 80 very brief chapters (the longest are maybe ten pages, the shortest less than one), our protagonist is Maria, a model and actress married to a successful movie director. By the time the story begins their relationship is frayed beyond repair; they have a daughter with unspecified psychological problems and Carter, her husband, has put her in an institution against Maria’s wishes. Carter is away most of the time on film shoots, leaving Maria alone in Los Angeles. She is on the verge of a nervous breakdown, sleeping outside by the pool and obsessing over getting out the door on time in the morning so she can drive for hours on the freeway with no destination.

While Didion’s writing is undeniably superb, I did not respond positively at all at first. In the interactions between Maria and her friends and professional acquaintances in Hollywood that make up much of the story, the point always seems to be how sordid and immoral they are. You can feel Didion’s disapproving stare trained on each of them. But, like, ma’am, you made these people up. The whole reason the magazine stories are compelling is because they’re about real people. Didion’s ability to cut someone to core and eviscerate their worldview is so amazing because she did it to someone real, who existed outside of her. For Didion to just invent some producer guy and have him say gross horny stuff and then for her to turn to the reader and go, “Look at how bad they are”? Come on, that’s nothing.

The book really turned around for me, however, when Maria discovers she’s pregnant. She tells Carter and confesses she can’t be sure it’s his. He forces her to get rid of it, giving her a number to call and offering no support beyond that. In these chapters, as Maria contemplates the decision, decides to acquiesce, and then endures the procedure, Didion’s writing comes alive. She finds something more interesting to say. The writing becomes almost stream-of-consciousness as Maria struggles to maintain coherent thoughts amid the crash of emotion. Finally Didion stops smirking and treats her character with some dignity.

Even before the abortion, Maria is a character chasing consequences. She feels out of place in her life of ease and will do anything to blow it up. But try as she might, she can’t make any consequences stick. When she sleeps with a famous actor, steals his car, and gets pulled over across state lines with weed in the glove compartment, Carter’s producer calls the right people and the whole thing is dropped. What happens then? Not only does Maria not know how to move her life forward but her efforts to destroy it are also thwarted. When even acts of negation are denied to you, what do you become?

I honestly have no idea what my final verdict is on this one. There are flashes of brilliance, and quite a bit that annoyed me, and in the end there’s a default to the sort of nihilism that Didion frequently projected onto others but that I think she just felt herself. I can’t fault it on a sentence level but it also feels like a lot of flash to distract from an underlying lack of substance. A novel-shaped filibuster, if you will.

Between The Acts, Virginia Woolf, 1941

A summer day, 1939, somewhere in the English countryside. A town prepares for a pageant that will raise funds electrify the church. The pageant, a history of England from Chaucer to the present, is to be held on the grounds of Pointz Hall, the home of the Oliver clan. They are Bartholomew, the old head of household; his sister Lucy, not quite senile but very much lost in her memories; adult nephew Giles, a strange, angry man prone to affairs who at one point stomps a snake and toad to death and spends the rest of the book with blood-smeared shoes; and his wife Isa, forlorn, unhappy in her marriage, a fount of murmured poetry she records in nondescript notebooks and never shares.

Returning to the compressed, one-day timeline of Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf here moves between the perspectives of her characters rather than focusing on one. Her abiding preoccupation with the way we think is on full display, nearly every line of dialogue or little event somehow juxtaposing objective reality to its perception or the feeling behind the words. It’s incredibly well done but will also make you despair for the possibility of genuine understanding between people, so weighed down is every moment by the baggage of all involved.

About one-third of the way through the story, the community takes their seats on the lawn and the pageant begins. This is where we can start to say what this book is actually about, but also where my interest waned significantly. Woolf gives us long sections of the play, intercut with whispered asides from the audience and the various ways the production is missing its marks, the wind is obscuring dialogue, and so forth. An early section, for example, representing the Elizabethan period, is a sort of Shakespeare mashup, a play featuring a false Duke, cross-dressing disguises, and other tropes of his, where only the first and last scenes are staged because there wasn’t time to rehearse the middle one.

In asking us to read these long sections while deliberately undercutting any dramatic effect they might have on us, what is Woolf doing? She is pointing us toward questions of when a work of art is complete and when it achieves that alchemical transformation from raw material to something more. In showing us the characters’ reactions to this rather shabby and piecemeal performance, she also asks what an audience brings to that synthesis and the conflict between generous receptivity and critical rigor.

This was Virginia Woolf’s final novel, published after her death. It comes with a note up front from her husband attesting that she had finished the manuscript but not completed revisions. There are ways in which this shows in the text—strings of adjectives that one imagines she might have pared back, for instance—but in another way its unfinished quality perfectly enacts the very questions she’s pursuing within. Does this book achieve thematic liftoff? What would that even mean?