Book Report May 2024

Do witches need insurance?

Sorry for the lack of writing this month. My goal is always to have at least one story come out between the book reports and I think this is the first time I’ve fallen short since last May. I have been writing like crazy but it’s all for articles with June news pegs so expect a lot in the coming weeks.

I’m always looking for reading recommendations! If you have an idea for something you think I would like or want to see written up here, please drop it in the comments or respond to this email.

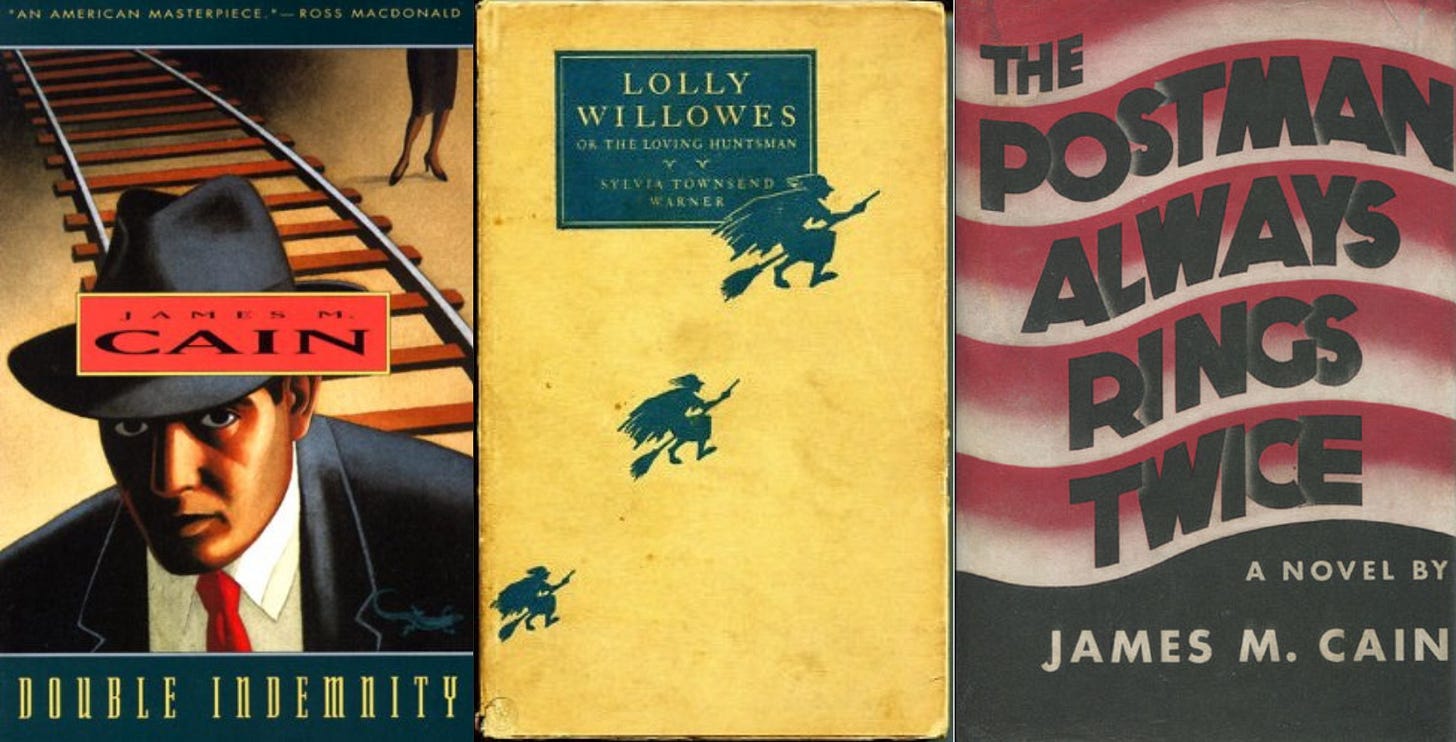

Lolly Willowes, Sylvia Townsend Warner, 1926

I love Lolly Willowes! I have no idea how this strange little book got on my radar but I’m so glad it did.

When the story begins, Laura Willowes is 28. She has grown up in a large house in the English countryside and was very close to her father. Now he’s dead and she’s moving in with her brother and his family in London. Laura, possessed of lively mind but not attractive, is already well on her way to spinsterdom but she feels no anxiety over it. Her brother and sister-in-law’s attempts to marry her fail due to her obvious lack of interest and intentional social sabotage. They accept that she’ll be a permanent fixture of the household and set her to work with housekeeping and childcare. The children call her Aunt Lolly, which becomes her primary identity.

Twenty years pass. For Laura, time slips by without her ever quite noticing or managing to get ahold of it. The days run together and she follows in their wake, never rousing herself to action or a consideration of what she wants her life to hold. Some faculty of imagination is missing. Warner’s descriptions of that slippage are wonderfully evocative and capture so well a feeling that has come to me with new potency since becoming a parent—devoting the day to keeping them busy, following the nap schedule, getting them up again and on to the next thing, such that I can reach the end of the day without my attention ever deviating from the concerns of the moment. The goal was to eat up time and it has been devoured.

But as she aged, certain rumblings began to gather in Laura’s soul. She dreams of dark woods and wild country, she remembers her childhood interest in herbalism. One day, now 47, she announces that she’ll be leaving her brother’s house in London and moving to Great Mop, a tiny village in the Chilterns, a hilly, wet, windy place with forest all around. Once she arrives, Laura spends her time walking the trails, meeting her neighbors, and being herself for the first time in decades. She’s loving it!

But then her nephew Titus visits and decides he’s going to stay for the whole summer. He’s a pain, needs help with things, and makes her feel stifled and cramped. Hiding away in the woods, she cries out asking isn’t there anyone who could help, who could make Titus go away. As she walks home she feels an overwhelming certainty that a pledge has been given and a compact has been made. She knows, without doubt, that she’s sold her soul to Satan and become a witch.

This occurs on about page 80 of a 120-page book. I won’t get into what happens after her transformation. Structurally, this is a very odd read: the first third is the sweep of 20 years, the middle third is her vibing in Great Mop, and the final third is Witch Stuff. I knew vaguely this book featured witchiness (look at the cover), so I was confounded as I read farther and farther and it kept not happening. But what Warner was giving me instead is just fantastic—she writes in that very classic English novelist Virginia Woolf sort of way that I adore. Good book!

The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, James Cain, 1934 and 1943

More than Chandler or Hammett, the Coens cite Cain’s crime and noir stories as an influence on their storytelling and attraction to similar material. I had intended to read a couple more Cain books in addition to these two in order to do a full essay about his work as part of the Coen Brothers series but there’s something about the genre that just shuts down my critical capacity entirely. I like them well enough but I have no thoughts, no insight on crime fiction and certainly can’t sustain an essay on them. So I’ll just stick my thoughts here and call it a day. Maybe I’ll watch the old movie versions of both these—I saw the adaptation of Double Indemnity years ago and mostly remember Billy Wilder’s fixation on Barbara Stanwyck’s anklet—and write about them in that context. We’ll see!

These two make a great pair because they’re both stories about committing the perfect crime and getting away with murder. In Postman, a drifter named Frank Chambers stops at a diner outside LA and takes a job there. He quickly starts an affair with his boss’s wife, Cora. They hatch a plan to off her husband, Nick, by making it look like he slipped in the tub and drowned. When they have to abort at the last minute, Chambers realizes that the trick to a perfect murder is not making it clean, but messy. New plan: get everyone drunk (for real), be seen struggling to get the car in gear, and stage a crash on a remote road. Chambers pulls these ideas seemingly from thin air—we never learn much about him and, despite his being the narrator, his thinking isn’t really conveyed. This is great, to be clear. Where his expertise on committing murder comes from is much less important than the way we’re carried along watching it play out.

Double Indemnity is sort of the Nintendo Power Official Strategy Guide version of this same plot. Walter Huff is an insurance agent who senses an opportunity when he pitches a housewife named Phyllis Nirdlinger and she asks about taking out an accident policy on her husband without telling him. There’s an attraction between the two of them, though I think it’s never actually consummated. Huff says that if they’re going to kill the husband they need to go big—the policy pays out a “double indemnity” (twice the money) if the victim dies in a train accident. Huff’s understanding of insurance allows him to foresee all the ways they could be caught or fail to get the payout, all of which he explains to Phyllis or directly to the reader as he winds his way between the legal and monetary pitfalls of his scheme. His scrupulousness in establishing his alibis—placing phone calls, making a bad impression on a movie theater usher—gave me an oddly inflected nostalgia for the analog world.

Insurance is the central concern of both books. There’s a lot of book left in Postman after the crime, which ostensibly hinges on whether Cora and Chambers will be tried for murder, but which is mostly about suspicions over Nick’s insurance policy, which was taken out too recently. The insurance investigator is to be the star witness for the prosecution. It’s by cutting a deal with the insurance companies that the defense lawyer is able to save the case. In Double Indemnity, Huff’s firm is central, obviously. There are long scenes of Huff, the company president, and their chief claims guy, Keyes, going through the facts of the case and spitballing strategies for beating the payout. Keyes tells the president to go mad-dog on Phyllis: have the police arrest her, get a murder confession by any means necessary. Keyes is a super fun character, this bizarre insurance savant who can smell a fraud 100 yards away.

Like other noirs from the time, the main thing here is the voice. Cain’s narrators talk in, well not exactly hard-boiled vernacular, but that sort of straightforward, unadorned American style that can take on a poetry of its own. I really like it but I don’t know what to say about it beyond that. That’s my impression in general—these books are great, enough said.