Liz is dealing with a real-life Bartleby situation and I can’t get enough. I refer, of course, to Melville’s classic short story Bartleby the Scrivener, in which a lawyer hires a new clerk who defers all tasks with the not-quite-refusal, “I would prefer not to.” Bartleby is a hero, an icon, one of the true originals, a pioneer of quiet quitting. He presages Kafka, Office Space, the financial crash, the Defector Quit Your Job shirt, and the end of history, frankly. He’s a self-care king, the GOAT of boundary-setting, a work-life balance visionary, and we have no choice but to stan a legend.

Anyway, it’s probably unwise for me to write about this but whatever. If any of you snitch to Liz’s boss you’re off the mailing list. Just before Liz went on maternity leave last August, the institution—not using its name obviously—hired a new accountant. This was supposed to be the resolution of previous problems with accounting, which for the last couple years had been outsourced to the larger organization Liz’s work is a part of. That accountant was extremely unhelpful and Liz would have to do everything short of moving her hands on the keyboard to get invoices paid and budget reports generated. We call this the Half Bartleby. Before that her work had its own accountant but when she was laid off she walked out on the spot, blocked the company’s number, and refused to answer any questions or provide any login credentials. We call this the Aggressive Bartleby.

Also if any of you call me a scrivener you’re off the list. The noble art of writing this free newsletter for literal dozens of readers has NOTHING in common with being a law copyist in the 1800s. These posts never have ink blots on them thank you very much just typos.

So this new guy—fuck it, his name is Anthony—was supposed to be the solution. Reader, he is not. When Liz returned to work in January it became clear that he does nothing and performs none of his essential duties. That means that no invoices are being paid to the numerous vendors the institution works with. It has now run out of essential preservation supplies for its collection because it’s impossible to order more with Anthony in control. When Liz’s boss pressed him on the matter on a zoom call, asking repeatedly “Are you going to pay the invoices?”, Anthony ignored the question and filibustered by rambling about some epic project he’s working on instead. This is Bartleby the Tech CEO.

He has not replied to a single email from Liz since her return and habitually cancels meetings at the last minute. He zoomed into one meeting clearly in some other office, monitoring some other screen. He never worked up an annual budget report for the boss to present to the board of directors, leading the boss to ask Liz for a copy of her personal budget spreadsheet, which Liz suspects was passed off as official without her knowledge or consent. The institution is now in default on certain debts due to non-payment. Oh and as a non-profit, under New York State law the institution gets audited every year.

Anthony is somehow, incredibly, winning. Despite bringing the organization to a standstill and threatening its very existence, he has not been fired. More than that—people are taking his side! No one besides Liz will acknowledge how dysfunctional things are becoming or how he’s making it impossible to do their jobs. When she tries to object to what’s happening, she’s now being treated as the problem! When she asked her boss if she can ever expect that essential budget report she was told, “Maybe next year.” It’s an object lesson in the way power operates, how it consolidates itself, and how people will identify and side with those wielding it best that someone so blatantly in the wrong has managed to fracture a benign workplace into bitter factions.

I’ve thought a lot about Bartleby over the last few years, both for its perfection as a story and his perfection as an embodiment of certain principles. In his book on Russian short stories George Saunders emphasizes the moment plot becomes story—that is, when mere events take on meaning beyond themselves. And he emphasizes asking constantly what is necessary to push a story to that point. Bartleby is pristine in this regard. Plot becomes story when Bartleby refuses to leave. If he were fired and just packed his things it would be a story of a boss who had a bad employee—not much meat on that bone. Melville needs a complication, which he finds in Bartleby’s attachment to the place. With his preference not to leave, Bartleby creates a thrilling contradiction—what is the workplace without work—and becomes a force of pure negation, refusing not just work but ambition, purpose, will. He calls into question capitalism, of course, but moreover the entire notion of human effort in an unfeeling universe.

But is Anthony staging a radical one-man protest? Is this performance art? Is he a disciple of Keynes intent on living out Keynes’ prediction of the work week shrunk to nothing thanks to technological improvement? Like Bartleby, I doubt we’ll ever find out. But in the meantime things are sure to get even more absurd and I’ll be laughing every step of the way.

Thanks as always for reading. This wasn’t my most productive month for books but here’s what I read.

The Tombs of Atuan, Ursula K. Le Guin, 1971

The second Earthsea book, in which our favorite wizard Ged is relegated to supporting player. Taking the lead instead is Tenar, a young woman selected at birth as the reincarnation of the First Priestess of the Nameless Ones. She serves chthonic deities worshiped in the Kargad Empire, an area mentioned by not explored in the first Earthsea. So Tenar grows up at the Tombs of Atuan, a remote desert holy place built above her gods’ underground domain of tunnels and labyrinths. She is given to the Nameless Ones, her identity consumed and her name lost. It’s a dull and lonely life, serving her sinister gods, who demand blood and occasional human sacrifice, but she finds a certain enchantment in growing into her responsibilities and communing with the dark as she explores the labyrinth below, learning by heart the subterranean world where she alone of mortals may tread.

Perhaps it’s obvious that her hungry masters of darkness and blood are malevolent and dangerous but for Tenar, isolated and illiterate, it’s difficult even to formulate doubts. That begins to change when she catches a thief in the Tombs. It’s Ged, come in search of a great treasure held deep within the labyrinth. As they build a relationship his frank talk of the outside world pierces the veil within which she lives. His presence in the labyrinth causes her a crisis of faith—Ged’s lack of immediate punishment for his transgressions must mean her masters don’t really exist. To which Ged replies basically, “Oh no, your masters are very real. Very real and very evil.” Le Guin uses this sort of two-step several times in their interactions, where it’s not that Tenar’s beliefs are wrong per se but that her knowledge is critically misframed.

Ged doesn’t enter the story until 100 pages of the book’s 200 have elapsed, making the first half an exercise in patience. The first Earthsea is a whirlwind tour that takes Ged from one corner of the world to the other, giving us glimpses of various locales. In her slow unraveling of one particular place in this one, Le Guin is clearly thinking through what a sequel should look like and how not to repeat herself. The patience pays off. Our protracted time with Tenar gives the reader a deep sense of her thinking and loads the decisions she has to make with real weight. And the long wait to see Ged makes his entrance all that much sweeter. In the stultifying rhythm of Tenar’s life in the first half of the book, there is a static, frozen quality, but when the thaw comes the story floods with emotion. There’s a profound sense that what came before was wrong and what’s happening now is right. It’s just lovely.

Eileen, Ottessa Moshfegh, 2015

There are no interiors here, only surfaces. Eileen, the deeply disturbed and abused narrator and protagonist, justifies her eating disorder and resulting emaciation by saying that she truly believed that her problems would be smaller if there were less of her. She longs to be noticed and plucked from her terrible life caring for her delusional, alcoholic father and working at a juvenile prison but she is a master of what she calls her “death mask,” an affected emotional blankness that conceals her roiling, spiteful thoughts. She tells us that library books saved her life—she memorized all the stains on the pages but tells us nothing of the words.

Eileen’s world changes and she’s jolted out of stalking one of the prison guards—he never speaks in the book, existing only as muscles and bulge—by the arrival of Rebecca, a glamorous, inexplicable figure, to serve as the prison’s new head of education. Rebecca is so unreal—highly idealized, beautiful, confident, but also with tendencies and fixations similar to Eileen’s—that one immediately clocks her as a figment of Eileen’s deranged mind. The story feels like it’s on the cusp of becoming a female Fight Club for much of its length, but then it doesn’t. We’re left to understand that Rebecca was real, I guess, but are never given the chance to see what makes her tick at all. Or maybe she is a hallucination—it doesn’t matter. She’s just another shiny image, in the end.

I was prepared to love this book. I read Moshfegh’s latest novel, Lapvona, last summer and was blown away—her character introductions there are Tolstoy-level blends of physical description, personality traits, even typical dreams. It’s genuinely virtuosic writing. Eileen also won the Hemingway Award for debut fiction. But it did nothing for me. Despite her darkness, Eileen is a very boring narrator and her disgusting habits and inner vitriol were simply tedious rather than shocking. For all of her endless elaborations on her dysfunction, there are no new layers of her character to be discovered. What you understand of Eileen by page 15 is not meaningfully different from what you understand of her by page 250. I will say that Moshfegh displays an admirable facility for dialogue; Eileen and Rebecca’s conversations have a push and pull of shifting dynamics that make each line dramatic—that’s quite impressive. But the plot never gets off the ground to take on a larger meaning or resonance—it’s some stuff that happens, until it stops.

Elements of Semiology, Roland Barthes, 1964

In college I read the canon in order so it’s a funny pleasure reading the canon backwards. Last summer I wrote about Baudrillard’s The System of Objects, where he goes deep on the signs and significations of the world of stuff—cars, furniture, houses, glass. I even mentioned that Barthes was on his dissertation committee. This slim volume basically sets the assignment that Baudrillard completed.

It’s a crash course summary of the project and principles of semiotics, the linguistic/anthropological field of signification. Barthes explains using linguistics as his chief example, exploring the link between a word and what it refers to, the signifier and the signified. But linguistics is just the clearest and most developed topic for semiotics: there’s a semiotics of fashion, of cuisine, of cars, even of furniture.

It’s all a little technical and abstract but it’s something of a skeleton key to understand what was happening with structuralism mid century. Right after college I was sure that semiotics was very important to the kind of writing and analysis I wanted to do and picked up the yellow Barthes Reader. I had a really hard time with it because it felt like I was expected to have a working knowledge of these semiotic principles. For the sake of reading other work of Barthes, Elements of Semiology is helpful homework.

A FEW GOOD LINKS

Defector: Which Three Fingers Did Ron DeSantis Use To Slurp Down Chocolate Pudding Like A Damn Raccoon?—This wins my monthly award for article I tried to read out loud to Liz while cry-laughing incoherently until she begs me to stop.

Unpopular Front: Why Culture Sucks—Speaking of Baudrillard, this piece from John Ganz’s excellent newsletter has lot of consonances my System of Objects essay and what I called the blandification of life these days—if you found that one interesting, you’ll like this because it’s much better executed!

NY Mag: The New Light Is Bad—Really fascinating and a great read. Scocca is unrivaled for starting with a gripe about how some small aspect of life is demonstrably getting worse and finding its deep ethical and social implications, while managing to stand outside the exhausting culture war framing everything is destined to take on now.

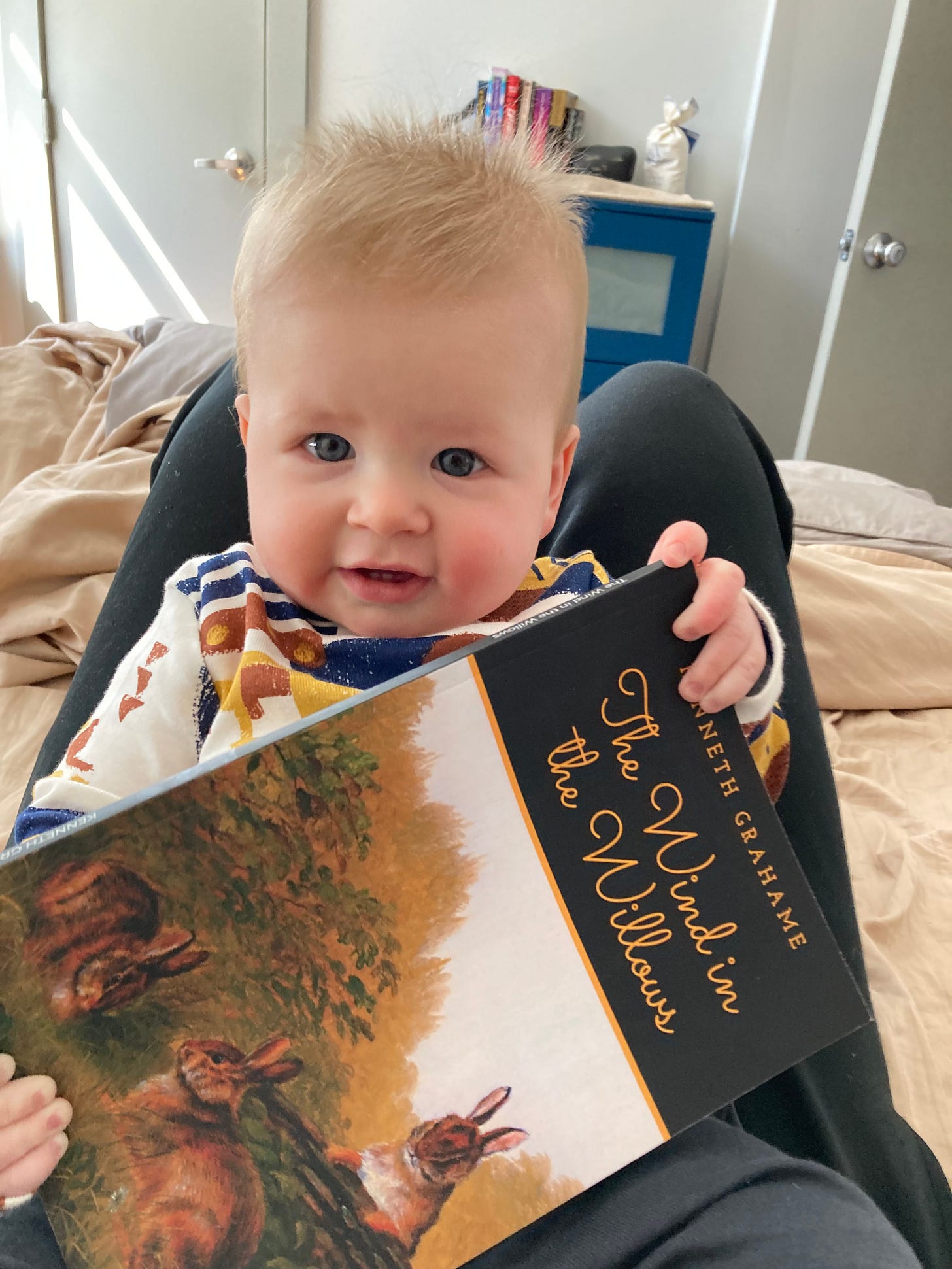

KIDS CORNER

The Wind In The Willows, Kenneth Grahame, 1908

[Gordon Ramsay voice] Wow, incredible. That is absolutely stunning.

Here’s another children’s classic that I’d never read before. I had no idea what I was committing to so what a profound joy it was to discover a masterpiece as I read it to Patrick. There’s just so much to love here. Grahame’s descriptive nature passages are lyrical and evocative and fill me with longing for the natural world. The comic sections are energetic and funny without being manic or exhausting. The characters are endearing and well-defined but well-rounded and believably real, despite being talking animals.

I must say a few words in particular about Toad. This maniac is a top-tier character. What a choice to make a toad an automobile fanatic who steals a car, loses himself in the thrill of gunning it down the highway (look up this section it’s the best depiction of an ecstatic experience I’ve ever encountered) and then spends chapters escaping prison and evading (human) police get back home.

The Wind In The Willows is an almost random book, in the best way. It is so unique, so inspired, that it feels like the product of a singular mind in a way so few things do. The details are strange and sometimes incongruous, but they somehow hang together. Grahame was an immensely gifted writer technically but reading this book is to feel the absence of any artifice—it is rich and full. It feels as if he is tapped directly into his deepest fount of creativity, that Calliope is speaking straight through him. I cannot recommend more highly.