Hello subscribers, old and new. There are more of you now, so I think a short reintroduction is in order. Who am I? Well, I’m a reader. I have no special credentials besides all old books I read at St. John’s College, which you can get a sense of from the seminar reading list. They keep fiddling with the end of senior year but the rest is exactly what I read. For the record I used my two “preceptorial” elective slots on Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Anna Karenina. I wrote my senior thesis on War and Peace. So that’s the baseline I’m working from. St. John’s is not a perfect institution but it profoundly shaped my sensibilities and gave me the tools to go from someone who liked to read to someone who could work with texts in a meaningful way. I also met my wife there, so thanks to it for that too.

Now that I’m doing these book reports, it seems obvious I should have been doing them since the day I graduated eight years ago. Let me try to fill in this period with a few of the most important things I read, offered without commentary: Middlemarch, The Magic Mountain, a lot of James Baldwin, a fair amount of Foucault, Minima Moralia by Theodor Adorno, everything William Gaddis ever wrote, Virginia Woolf, Calvino, David Graeber, and too much else I’m forgetting entirely right now.

The thing about books is, there are really a lot of them. Far from feeling well-read, the more I read and learn of new authors, new connections, new literary currents and genealogies, the more do I feel overwhelmed by all that I have not read. And that’s great! Reading has been my life’s passion since I could decipher words and probably before that. It would be the blackest despair if there were nothing left to read. There’s no feeling like discovering a new author who really has the goods and knowing they have other books I’ll be able to read eventually.

But as someone who has always struggled with self-consciousness (that’s right, I’m a writer), I find myself worrying over these book reports for the way they reveal what I haven’t read before. How can I have the nerve to judge anything when I had never read Dead Souls until this month, I ungenerously imagine readers asking. But that’s ridiculous, because 1) all Underline subscribers are ethereal beings of pure light incapable of rude thoughts, and 2) we know we all have to start somewhere. Filling the bookshelves of the soul is the work of a lifetime and can never be finished.

But it is daunting! I learned of both Clarice Lispector and Natalia Ginzburg so recently. Reading about Lispector in this New Yorker article was almost panic-inducing—she’s the greatest and most acclaimed Brazilian writer of the 20th century and I’ve never heard of her before? That’s a terrifying thought, because then who else like her remains totally unknown to me? I had a similar experience when Annie Ernaux won the Nobel last year.

This is a roundabout way of saying: Send me your recommendations!! I am always looking for stuff to read and cover in this column. I know I have major blindspots, gaps in my knowledge, genre biases. Poetry is a mystery to me. I want to correct these lapses but I need help. So hit me up, either via email or comment and let me know. Authors, specific books, whatever, do it and help me put my fears to rest.

Dead Souls, Nikolai Gogol, 1842

Speaking of gaps in my knowledge, I did not know that Dead Souls is extremely unfinished. Gogol promised a three-volume epic but he only completed and published the first part. As a result, the story we have takes quite a funny shape. A nondescript gentleman, Chichikov, arrives in a provincial town, spends a week or two charming all the officials and landowners, and then begins making a series of housecalls. His approach varies in each of these interactions, which make up the majority of the book, but his goal is the same. He wants to acquire the landowners’ “dead souls,” that is, male serfs who have died since the last census and remain on the tax rolls. His offer would lift a tax burden off their shoulders for no apparent gain of his own, which raises their suspicions.

Chichikov holds his cards so close to his chest throughout that it’s hard to know what to do with him as a character. The portraits Gogol draws of his interlocutors, however, are marvelous. There’s Nastasya Korobochka, a batty widow who agrees to sell her dead souls if Chichikov promises to return to buy butter and various sundries; obsequious Manilov, so enamored with Chichikov that he refuses to go first through a doorway until both are squeezing through at the same time; dissipated gambler and compulsive liar Nozdryov who almost has Chichikov killed because he won’t wager the dead souls on a game of checkers; and the disturbing Sobakevich, an old miser whose estate has fallen to ruin through his obsessive hoarding and rationing, what has killed off most of his serfs (Chichikov’s ears prick up in excitement). I could read 400 pages of Chichikov just visiting one house after another, Gogol is so skilled at sketching these figures.

Having made his purchases he returns to town. There’s a great little scene of nonsense bureaucracy when he tries to get his deeds of purchase certified—a wellspring for Kafka, Bulgakov, and Terry Gilliam. When the town learns of his actions there’s a scramble and the possibility he’ll be mobbed. This is the weakest part of the book as there’s a great deal of talk between characters who are identified only by their titles—the prosecutor, the governor—and lack personality, making them hard to keep straight. But Chichikov rides away in his carriage before they can reach him. Success, end of book, lmao.

The tale is delivered by a delightfully off-kilter narrator. His attention often diverges from the action as he spins out Homeric similes that stretch in for multiple sentences. He makes a show of his love of mother Russia but clearly finds the town and people squalid and banal. He rambles while Chichikov rides in his carriage as if he has to fill the travel time. I’m fascinated by the cinematic sense of these passages, by the way reading time is equated to motion within the story. They seem a distant forerunner of the “tracking shot” transitions Gaddis employs in JR.

My edition contains four chapters from the uncompleted Part 2, which are themselves unfinished and discontinuous. Part 2 seems to have been not unlike Part 1, in that Chichikov goes to another town and inserts himself into the proceedings. But it seems like it would have been even better. The secondary characters are vivid and lead from one to another as he worms his way into the community in a pleasing way. There’s a promising but incomplete plot about Chichikov getting himself written into a rich old woman’s will just before she dies and then that deception being discovered. What we have of Dead Souls is monumental but I mourn the work that could have been.

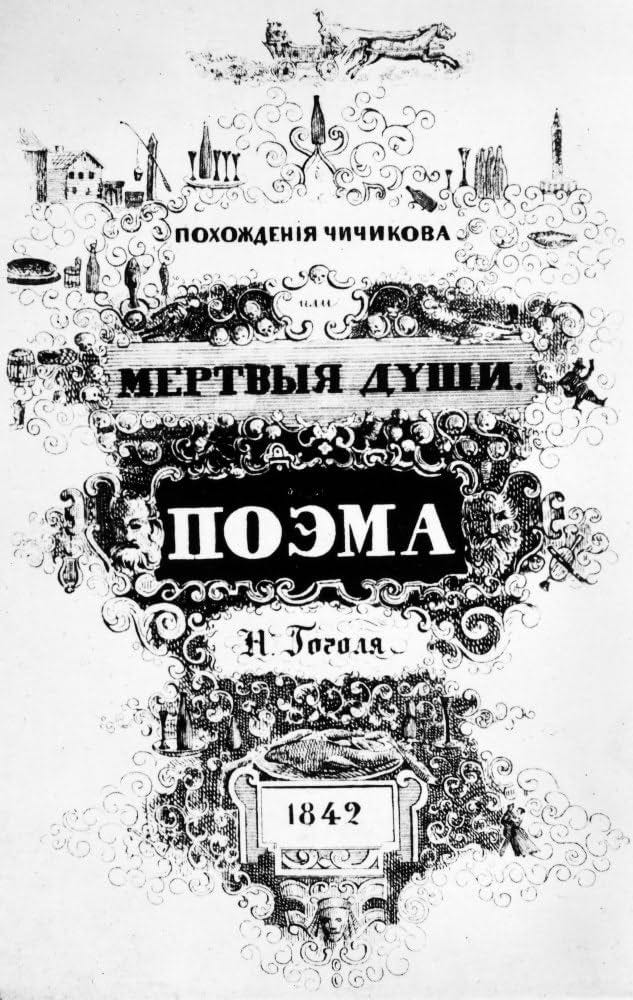

PS: In their introduction, Pevear and Volokhonsky describe the original title page, which Gogol designed himself. I found it online and it’s cool so check it out:

The Hour of the Star, Clarice Lispector, 1977

This one is… wow. Published months before Lispector’s death, The Hour of the Star is a strange, spiky bit of oratory from another odd narrator. There’s a story here, concerning the hard life of an unfortunate young woman from the provinces, but we’re not invited to take it seriously. The book is only 80 pages long and the first 20 are the narrator clearing his throat. In between metaphysical wanderings and luscious passages on the ontological status of story, he—and it is a he, named Rodrigo—says repeatedly that the narrative of the “northeastern girl” is a story he has inside him, a story he simply must release by putting it down on paper. As the action unfolds, he breaks in to question his authorial choices while insisting he’s not in control, rather the story is master over him.

It’s hard to know what to say in the abstract about this book. It needs to be read. Lispector’s writing, with its unconventional punctuation and leaps in logic, is destabilizing, challenging, and completely brilliant. This is a writer who achieved immediate success and fame with the publication of her first novel at 23, Near to the Wild Heart, reflecting on and synthesizing her life’s work to tell us as clearly as she can what it was all about. I try not to quote excessively in these columns, but this passage goes right to the heart of it (Benjamin Moser translation):

I intend, as I earlier suggested, to write in an ever simpler way. Anyway the material I’ve got is too plain and meager, the information about my characters sparse and not very elucidating, this information that painstakingly comes from me to myself, it’s a carpenter’s job.

Yes, but don’t forget that to write anything at all my basic material is the word. So that’s why this story will be made of words that gather in sentences and from these a secret meaning emanates that goes beyond words and sentences. Naturally, like every writer I’m tempted to use succulent terms: I know splendid adjectives, meaty nouns, and verbs so slender that they travel sharp through the air about to go into action, since words are actions, don’t you agree? I’m not going to adorn the word because if I touch the girl’s bread the bread will turn to gold—and the girl (she’s nineteen) the girl wouldn’t be able to bite it, dying of hunger.

What is there to say except wow?

The Little Virtues, Natalia Ginzburg, 1962

A novelist and an essayist, Natalia Ginzburg and her first husband Leone Ginzburg were also fierce anti-Fascists in the 30s and 40s. During the war they lived in exile in Abruzzi, Ginzburg’s account of which is the first essay in this collection. They would secretly return to Rome to edit an anti-Fascist newspaper until Leone was caught. He was tortured to death by Mussolini’s thugs. “Winter In Abruzzi” is thus a stunner and a heartbreaker—she draws a dismal scene of homesickness and leaky roofs before executing a flawless, textbook reversal: these were the best days of her life because he was there and they didn’t know how it would end.

These essays were written between 1944 and 1962. They concern poverty, the mystery and power of our social entanglements, and writing as a vocation. There’s nothing flashy here. Ginzburg writes simply, with a steady, piercing gaze, each line a testament to her hard-won wisdom. To her credit, she’s also very funny—among the more serious pieces there’s also one devoted entirely to clowning on how bad the food is in England.

I’m a father now and my moral sensibilities have been indelibly shaped by Plato and Aristotle, by The Meno and the Nicomachean Ethics. Tell me Socrates, can virtue be taught? I sought this collection out on the promise of the title essay, The Little Virtues, because raising my son to value the Good Life, as Aristotle called it, is of supreme importance to me. Here’s how Ginzburg begins that piece:

As far as the education of children is concerned I think they should be taught not the little virtues but the great ones. Not thrift but generosity and an indifference to money; not caution but courage and a contempt for danger; not shrewdness but frankness and a love of truth; not tact but love for one’s neighborhood and self-denial; not a desire for success but a desire to be and to know.

That last one is everything to me. The rest of the essay lives up to this stunning opener and, with regard to shaping their relationship with money in particular, contains some very good practical advice.

I’m an essayist, I suppose, though that term has always felt a little grandiose for what I’ve put out into the world. I’ve spent a decade thinking about structure above all, what I must do to get a piece of writing to function. But there’s more to writing than that, and greater rewards to be had. As Ursula K. Le Guin reminded us, the writer’s reward is freedom. Ginzburg is fearless with structure and length. She is supremely confident that her clarity of purpose and unsentimental honesty will carry the day. She knows she can write whatever she wants, provided she knows it to be true. I feel freer for having read it.

KIDS CORNER

What I’m reading to my 10-month old

The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett, 1911

I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that goes off the rails as badly as this. Where do I even begin? I get the impression The Secret Garden retains its aura as a children’s classic but few actually read it these days. Maybe there’s a good reason for that! Let’s get into it. I’m sorry this is so long.

Our protagonist is Mary Lennox, a spoiled nine-year-old raised in India on account of her parents doing some British colonial shit there. When everyone else in the household dies of cholera, she survives because she’s so neglected and forgotten no one gives her the tainted water to drink. Besides some extremely dated language and attitudes, this opening features a number of red flags that should have signaled the problems to come. Mary has severe behavioral and emotional problems, which to me seems understandable given how clear Burnett is that she was unloved and unattended to but conversely accustomed to getting her way in all things. That’s not how the author sees it though. She judges her character harshly, over and over, disapproving of Mary’s “sour face” and temper, acknowledging the factors in her life that would beget them while expecting her to simply be better than that.

So she’s quickly packed off to the Yorkshire moorland estate of Misselthwaite Manor, owned by her uncle Mr. Craven. He’s a reclusive, broken man on account of his wife’s death ten years earlier who spends most of his time traveling on the Continent. The house is massive and mostly shuttered, the servants are not friendly; the book seems to be setting up Wuthering Heights For Kids, but then not really. Mary gets into going out into the gardens, which nearly instantly effects a complete metamorphosis. Suddenly she’s patient and concerned with others and generally pleasant. I expected these changes to be spooled out more slowly but goodness basically functions like a lightswitch here.

Yadda yadda yadda there’s a secret garden that’s been locked up since Mrs. Craven died, Mary finds the door, she’s in the garden and she wants to revive it. She befriends a peasant boy named Dickon who spends all his time on the moors and has preternatural abilities with plants and animals. They begin working in the garden and Burnett again demonstrates she’s maybe not quite in control of her work when she describes their gardening in language that’s dripping with sexuality, all thrusting into moist earth and stalks bursting forth in readiness and Mary lying back satisfied. It’s weird!

Halfway through, The Secret Garden more than anything is a pseudoscientific screed about the power of fresh air. I really can’t emphasize enough how much space is devoted to the idea that Mary’s moral transformation is entirely the result of her spending time outdoors, not because she has a friend and a passion project but literally because of good breezes. But then, she discovers a shocking secret: there’s another child in the house. Mr. Craven has a secret son who’s bedridden and kept in a concealed corridor. Colin is haughty, petulant, bossy—just like Mary was—spoiled because of his vague illness and the expectation he will die soon. Despite my above criticisms, the book is basically readable up to this point but it’s straight downhill from the moment Colin appears.

As an aside, the book’s humor, such as it is, consists of the way the servants speak “broad Yorkshire,” so be warned, if you plan on reading this to your kid many characters say “tha” for “you” among other rustic substitutions and shortenings. Eventually Mary and Colin begin trying to learn and speak Yorkshire, which has big Steve Buscemi “How do you do fellow poors” energy. It must have been hell for Liz to listen to me read this to Patrick.

Anyway, back to Colin—I hate this kid so much. He obviously shares a lot of traits with Mary—spoiled, neglected—but they are mediated by his status as an invalid in a weird way. His arc, which takes over the back half of the book and eclipses Mary entirely, is to learn that he’s not actually sick and he’s going to live. This means his actual character flaws are left untreated, so to speak, so at the end he’s every bit as domineering and possessive as he began. Mary tells him about the secret garden, which made my heart sink, and he proved me right by saying with no hesitation, in effect, “Cool, that’s mine now.”

So Mary and Dickon take Colin to the secret garden, now revitalized and in bloom, and he has a triumphant moment of standing up from his wheelchair and proclaiming that he’s not going to die, he’s going to live. This is where the book should end, but unfortunately there’s another 75 pages left. Colin is a terribly thin character. Without his tragic backstory there’s nothing to him. He reads as an inadvertent bit of critique on the power of wealth and status to obliterate thought and mind. He seizes on the notion that the garden has some magical properties that are the source of his revitalization and seeks to test and prove his theory of the Magic (always capitalized). The story descends into ad nauseum improvised sermons by Colin as he rhapsodizes about the Magic and how he’s going to live and how he’s the most special goodboy etc. In addition to Mary and Dickon he inexplicably recruits the elderly gardener Ben Weatherstaff into his little cult. One day Dickon returns from town with the good news that he spoke with the village strongman (?) and got a demonstration (??) of his exercise routine (???), which they can now practice in the garden (????). I genuinely could not believe it when they turned the secret garden of Colin’s dead mother into a crossfit gym.

More bullshit happens. There’s a whole thing about how Colin doesn’t want his father to get the news by letter that he’s gotten better, he wants to surprise him with it face to face, so he and Mary pretend to be on a hunger strike while secretly eating in the garden. These antics recall a Tom Sawyer attending his own funeral sort of thing but if Mark Twain got bonked on the head. There’s a good payoff to this actually, in that they think the servants must be going crazy trying to figure out how to get them to eat but the servants simply don’t give a shit. Here I should mention that earlier it’s implied the doctor is tricking Colin into thinking he’s sick, Munchausen by proxy-style, but that thread is dropped and forgotten.

It’s so funny to me that for how much this book is a paean to nature they never leave the manor. Dickon’s exploits out on the moors are a constant point of discussion but Mary and Colin never even consider going out there themselves. They are perfectly content at home, in their safe and tidy simulacrum of nature, their literal walled garden. There’s a metaphor here somewhere.

As Burnett struggles to fill these pages—it feels like she had a minimum page count to hit—she begins mixing in straight narration about the power of positive thinking and how Mary and Colin’s problems all stemmed from their negative thoughts, not their obvious trauma and neglect. She thinks she’s Tolstoy writing the Second Epilogue but she’s actually writing The Secret. The last chapter brings these idiotic thoughts to their apotheosis as she describes Mr. Craven’s sorrow—again, over his dead wife and invalid son—and proposes that he should simply be happy, reproaching him that he had “let his soul fill itself with darkness and had refused obstinately to allow any rift of light to pierce through.” But not only is it bad for him, she goes even further: “Darkness so brooded over him that the sight of him was a wrong done to other people because it was as if he poisoned the air about him with gloom.” That’s right folks, bad vibes are violence, actually!

This is a story about moral transformation that has no theory of morals or mind or transformation. Its only metaphysical beliefs are vague, New Age-y nonsense that put the onus of living well on victims without taking seriously their suffering. I found it borderline offensive in addition to totally braindead. The Secret Garden has been read for one hundred years now and that’s more than enough.

Ps— I enjoy a good rant. This was very good.

Patrick is probably going to love The Secret Garden, and then you’ll be in a fix.