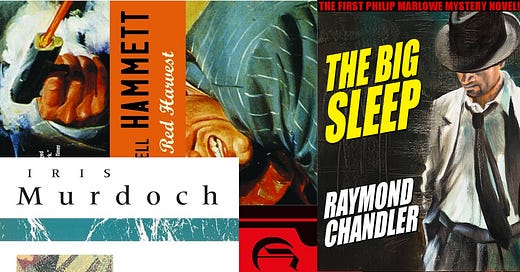

Under The Net, Iris Murdoch, 1954

This is a challenging book to talk about because it has so much plot that all hinges on relationships the main character had in the past. I’ll try to be as brief as possible. Our protagonist is Jake Donaghue, an underachieving writer who scrapes by translating airport fiction. Years earlier he fell into an intense friendship with the industrialist Hugo Belfounder; they spent their time debating philosophy and politics, with Hugo habitually taking the role of a child asking “why?” over and over until the foundations crumbled under all of Jake’s ideas and he was reduced to silence. Jake started writing down their conversations as a way of thinking about them more, then began touching them up into a proper dialogue, and eventually sold it to a publisher. He felt so guilty over profiting off Hugo’s ideas that on the day of publication he ghosted him and they never spoke again.

In the present, he comes into contact with some other former acquaintances who turn out to be connected with Hugo as well. Jake decides he must reconnect with him and spends most of the story trying to find him. Along the way he steals a movie star dog from a bookie named Sammy Starfield who has himself stolen one of Jake’s translations in an attempt to sell the movie rights; goes pubcrawling and makes friends with “Lefty,” a socialist leader; and sneaks into Hugo’s movie studio just in time for it to be raided by the police.

I read Murdoch’s final novel, Jackson’s Dilemma, last year. This was her first. As a debut, it’s certainly daring. Premising the plot on so much backstory is a big swing. The action is comic but the tone is melancholy. It defies easy categorization and easy resolutions. Murdoch, who was a philosopher in addition to novelist, freights her madcap plot with deep and surprising ruminations. Jake is not unlikeable, per se, but he is consistently frustrating and drove me crazy every time he did something impulsive that worked exactly counter to his own interests and goals (couldn’t be me!).

For all I like about Under The Net, though, I found it rather exhausting. This might be a me problem but I couldn’t read more than a chapter at a time and the way it’s overstuffed with incident just wore me out. Like Jake wondering why he can’t commit to anything and be the artist he wants to be, I spent my time reading this wondering why I couldn’t hold my attention on it or appreciate it at the level I thought I should. It’s a book about disappointment, so I suppose it’s fitting.

The Big Sleep, Raymond Chandler, 1939

Classic noir and detective fiction is a big blindspot of mine, which I’m finally trying to rectify. Do I need to tell you what this is about? It’s the first of Chandler’s Philip Marlowe series, the LA private eye played in the movie version by Humphrey Bogart. Marlowe is summoned to the home of the dying General Sternwood because he’s once again being blackmailed for something involving his wild younger daughter Carmen. The plot spirals from there, takes a turn for the murderous, and brings Marlowe into contact with smut peddlers, casino owner Eddie Mars, and other underworld figures. All the while the question of what happened to the bootlegger husband of Sternwood’s other daughter Vivian hangs in the background.

Chandler, compared to Hammett, was famously careless in his plotting, often leaving key details unexplained. When Howard Hawks made the movie he asked Chandler who killed the chauffeur and Chandler said he had no idea, never having thought about it. So I was surprised reading The Big Sleep just how comprehensible it is. The case has a number of different threads but it’s not that tangled a web.

What holds this story together is Marlowe. His narration is so much fun, just a perfect blend of wry observation, genuine charm, and old-timey alcoholism. It’s actually plausible when he sweet talks people into giving him the information he needs because Chandler writes him so well as a disarming mix of honest and deceptive, aggressive and encouraging. He wraps up the official case General Sternwood hired him for halfway through the story but keeps pulling on loose ends because he just cares too much dammit! Classic stuff.

Red Harvest, Dashiell Hammett, 1929

On the other hand, this. So Hammett, whose career overlaps with Chandler’s but began in earnest earlier, is maybe the key figure in the development of hardboiled fiction; his own detective Sam Spade, in The Maltese Falcon, is a direct progenitor for Philip Marlowe. This one is certainly hardboiled, though in this case I’m not sure that’s a good thing.

Red Harvest stars the character known as The Continental Op. He’s a never-named employee of the Continental Detective Agency, a thinly-veiled version of the Pinkertons, which Hammett was an agent for earlier in his life. The Op has been dispatched to Personville, aka Poisonville, a rancid Montana mining town ruled by a syndicate of criminals. Like The Big Sleep, his client is an old bedridden man, Elihu Willson, the owner of the mining operations, who lost control of his city when he brought in thugs to break a strike. After giving the Op carte blanche to clean house, he rescinds his permission but it’s too late—the crooked chief of police has tried to assassinate the Op so he keeps Willson’s money and declares a one man war on all crime in Poisonville.

His plan, loosely speaking, is to play the criminal elements against each other—stir up trouble between the gambler Max “Whisper” Thaler, bootlegger Pete the Finn, and several others. This is where the book bogs down. For more than half the story the attention is on Whisper alone, with Pete the Finn appearing only in one or two scenes and another of the crime lords, Lew Yard, killed offstage, never having stepped onto it.

This is a brutal, grim story. The Op engineers (and commits!) murder after murder but never betrays any feeling about it either way until very late in the book when he says all the killing is getting to him. The problem, though, is that none of the violence really hit home for me as a reader. There’s an odd, dreamlike quality to Red Harvest where the Op will look out his window and see cars screaming past with men firing at each other but once they pass out of sight no more thought is paid to them. It’s as if the Op is watching the consequences of his own actions from the other side of screen, where none of it can actually affect him.

Anyway, I read this primarily because it’s where the Coen Brothers got the title “Blood Simple.” When the Op complains the killing is starting to affect him he says, “This damned burg’s getting me. If don’t get away soon I’ll be going blood-simple like the natives.” It’s probably not the best reason to choose a book but it was a quick read.

Carmilla, Sheridan Le Fanu, 1872

Liz and I are watching True Blood so I have vampires on the brain, the sexier the better. This story, which predates Dracula by 25 years, certainly fits the bill. It follows Laura, an 18-year-old who lives with her father and servants in an isolated castle in the forests of Styria. When a carriage carrying a stately woman and her beautiful, slightly sickly daughter overturns outside the gate, the mother asks Laura’s father to take in her daughter while she continues her journey. He agrees, obviously. This daughter is Carmilla, who suffers from “languor,” locks her door at night, and does not come out until the late afternoon.

Carmilla develops an intense fascination with Laura and is prone to cuddling her, kissing her, and making strange statements about how Laura will follow her into death where they can be together forever. Laura finds her feelings about this behavior ambiguous, both repulsed and intrigued. Her ambivalence intensifies when she begins to suffer from languor herself, along with strange dreams that are often punctuated by a feeling of two needles piercing her neck.

For a modern reader, it’s not hard to figure out what’s going on here. What’s interesting about reading one of the first vampire stories is thinking about what’s taken for granted and what constitutes a surprise. There are no twists as far as we’re concerned. The portrait of Laura’s ancestor who looks exactly like Carmilla is in fact Carmilla, she is a vampire, and she does get staked in the end. And that suffices for a story—there’s no need to add a wrinkle to the narrative, or to wonder about Carmilla’s emotions and desires, or for Laura to sympathize with her. No, vampires are a simple problem that, once dealt with, need not be considered further, like roaches.

I also think it’s interesting that vampires, which have an incredible ability to function as a metaphor for just about anything, are absolutely not a stand-in for anything here. They’re supernatural, certainly, but they’re also very literally just that. Sometimes a revenant is just a revenant.