And we’re back. Parenthood is wild, man, has it been two weeks since I wrote one of these or three years? I have really missed working on these, though I certainly haven’t had the time. The catch-22 of being a new parent is I’ve never felt more creative and inspired in my life but I haven’t been able to do anything with all the ideas that I’ve had. And if I don’t jot them down somewhere I forget them immediately and they’re gone forever!

Full length essays still feel a little beyond me for the moment but this is a books newsletter and I’m still reading regularly and I need an outlet for my takes on all of it. I’ve been watching nothing, playing nothing but have been prioritizing reading. I make the same discovery every year during Dry January that I read a lot more when we’re not drinking in the evening. Weird!

Anyway, look forward to a post like this each month going forward. Maybe if I manage to watch a movie at some point I can tell you about that too. Thanks for reading, here’s what I’ve been reading.

The Crossing, Cormac McCarthy, 1994

A story of doomed enterprises and untidy endings. In this non-sequel sequel to All The Pretty Horses, 16-year-old Billy Parham traps a wolf and instead of killing it decides to return it home to the mountains of Mexico. This journey ends poorly. But when he eventually returns to his family’s ranch in New Mexico he learns the real calamity happened there—horse thieves killed his parents while he was away. He and his brother, Boyd, return to Mexico, wandering in search of their stolen property and any reason to continue on.

In the course of these wanderings Billy hears multiple long tales about men whom calamity befell and then walked the earth enlightened, either challenging God, Job-like, or without illusions or aspirations now that the veil of meaning, of narrativization, was lifted. Billy turns out to be just such a figure and his journey depicts at length what he’s told in miniature—the minor conversations and incidents that would make up such an aimless, peripatetic existence. But whereas the men in the stories achieved some sort of wisdom, whether outraged or resigned, Billy does not. He is resolutely stony, generating goals and chasing them endlessly. The very end of the book suggests that he finally breaks from this pattern and lets his loss flood in, but rather than do the work of depicting this moral transformation, McCarthy cuts us off.

Maybe forewarned with this description you could enjoy the book for what it is, but I spent the middle 200 pages pulling my hair out waiting for something to happen or anything to cohere. McCarthy’s descriptive powers remain exemplary and his trademark passages about the heart of the world and the blazing firmament above are beautiful as always. But they come off as cheats when the character- and story-work surrounding them are so lacking. A book that’s far less than the sum of its parts.

Coventry: Essays, Rachel Cusk, 2019

I loved Cusk’s Outline trilogy, which took the form of a series of conversations between her unsparing narrator Faye and various interlocutors. Cusk displayed such a keen ability to cut straight to the heart of situations and characters—ruthless but never cruel—I was very curious to see what she could do in more conventional essay form putting her unvarnisihed thoughts on display. Then the book sat on my shelf for three years unopened.

I’m glad I waited. The best pieces in this collection concern marriage and parenthood and how they demolish our old identities and challenge us to rebuild our private worlds under harsh new conditions. Much of her analysis is devastating, an unflinching pursuit of the truth above all in all its discomfiting power, but also edifying. She makes a funny observation in her piece about her kids becoming teenagers that it was the first time anyone admitted that having kids could be difficult. She does not lie to her readers this way. Life is hard. But the work is the thing and honesty is the best tool.

Cusk is incredibly gifted at working with very broad topics. When approaching a concept in full, as in the piece “On Rudeness,” it’s frustratingly easy, I know from experience, to get lost in abstraction. The writing becomes vague. She knows how to move back and forth from the abstract to the specific and back, zooming in and out to establish principles and fill them in with detail. There’s a lot to learn from her technique. This extends to the book introductions and reviews included as well. Her writing is so sophisticated but unpretentious; she tells you exactly what a book is really about so simply it’s undeniable. Her powers of observation are astonishing.

Another Country, James Baldwin, 1962

This is a tough one. The first 150 pages of this novel are so unpleasant I bailed the first time I tried to read it a few years ago. They are a whirlwind of domestic violence, suicide, and confessions of casual sadism. And there’s something just off in the writing that compounds the repellent subject matter. Then something shifts. The breakneck pace slows and a couple new characters take the spotlight. The story settles into a different rhythm. Baldwin renders his New York with greater specificity, giving his characters regular bars and clubs where they run into acquaintances, which throws into relief how impersonally drawn it all is at first.

The story operates in two opposed modes. When we go inside characters’ minds their thoughts and feelings are deep and expansive, the kind of openness to the fullness of existence that always feels just out of reach. It’s amazing writing, Baldwin at his best. But then we get talking scenes and they’re deadly dull. A lot of dialogue in this book is legit smalltalk and it’s so boring. I get the project implied here: to render the gulf between the banal happenings of our lives and the volcanic rumblings of our souls but it’s better in concept than execution.

Baldwin is at great pains to capture how people speak. He gets the slang and he italicizes constantly to convey emphasis (which I find grating) but there’s something off about how people converse. They answer each other both too directly and somehow not at all. Real conversation is the opposite. People answer each other in ways that seem not to be responses in the least but turn out precisely to be.

I respect the boundaries Baldwin was pushing with his depictions of interracial relationships, infidelity, homosexuality, and particularly bisexuality (every dude in this book is bi!), but I don’t love it. It’s from the middle stage of his career, following the early brilliance of Go Tell It On The Mountain and Giovanni’s Room and before great late books like Just Above My Head. Baldwin seems to be working through what his books should be like. I don’t think it’s successful but there’s a lot to chew on. Ugh I have enough to say about this one I should probably write a full post okay gotta stop here.

KIDS CORNER

Orlando, Virginia Woolf, 1928

I forget when exactly but it was probably when Patrick was around 10-12 weeks old I decided to start reading adult books to him in addition to his picture books. The first one we tried was Gulliver’s Travels but it wasn’t right. Besides it being a slow descent into total misanthropy, the writing wasn’t what I was looking for to read aloud. The book’s greatness is in its ideas and not so much its sentences (sorry Swift!). But it clarified what I was looking for, which was lovely writing, flowy sentences, not too much dialogue.

Orlando fit the bill perfectly. And it’s 400+ pages so it kept us occupied for a long time, so I’m fudging a bit including it for this month but whatever. I really enjoyed reading it again and Patrick became notably more engaged over the course of the book, which was amazing. There’s one passage where Woolf describes how Orlando’s estate has fallen into disrepair and repeatedly used the word “damp” until Patrick started giggling each time it recurred. It’s now one of his favorite words and always makes him laugh. Others include “egg,” “grunge,” and “cream.”

My only quibble is Woolf’s habit of interrupting her nice sentences with parenthetical undercutting asides. They break the flow and make the sentence harder to follow for a listener. Otherwise, no notes, read this book to your baby.

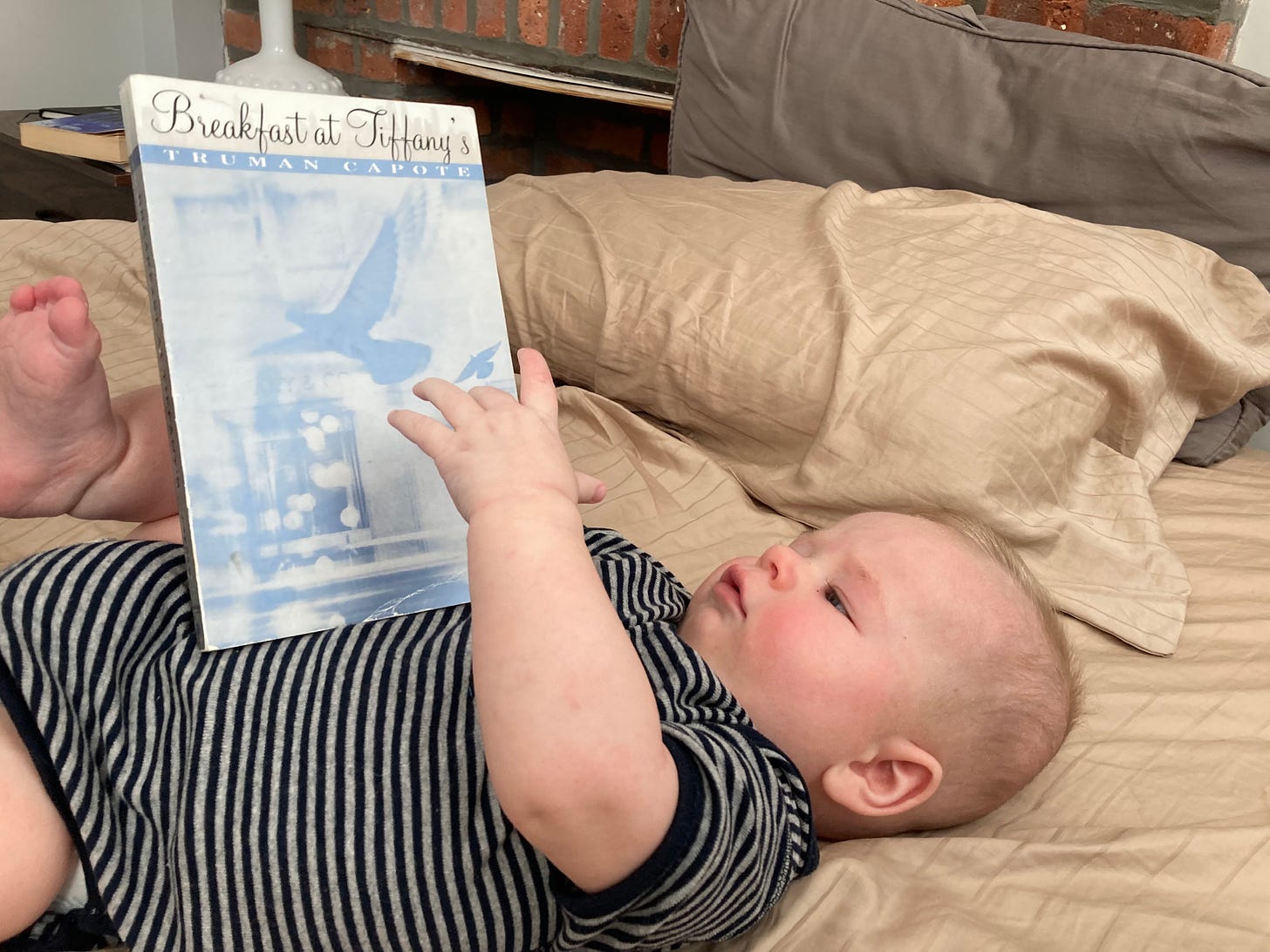

Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Truman Capote, 1958

I had never read this, though Liz had, so it was interesting to sightread it aloud. I love Capote—he writes such perfect sentences, each one with a rhythm that crests wonderfully on the final, indelible noun. God he’s so good. Reading it out loud made me appreciate his gift for dialogue as well. He gives each of his characters different rhythms and habits that are so right for them, like the movie producer Berman, who speaks in staccato half sentences strung together, all business, versus Holly Golightly’s more singsong run-ons that jump from topic to topic with her train of thought.

As baby material, the abundance of dialogue was a little challenging, particularly because the characters are all quick-talkers and the urge to render that cadence will push you to read faster than your kid can probably quite keep up with. It’s a wonderful story but maybe save it for yourself.

Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino, 1972

Marco Polo sits with Kublai Khan, describing non-existent, fantastical cities he’s visited—one that is nothing but the plumbing, left perfectly intact, of buildings long demolished, another built according to cosmic principles, the design of the gods, which has produced nothing but monsters. This is not my favorite Calvino of what I’ve read—that would be If on a winter’s night a traveler—but it really came together for me at the end. I’m a big fan.

I figured a whole book of short little sections of prose poetry would be perfect as something we could pick up and put down as needed. It never quite seemed to capture Patrick’s attention or delight him though. What can I say, they’re fickle little creatures.