I’m not doing a year in review post so I’m going to use this space to say: thank you for an incredible year. In 2023 I wrote more than I have any year previously. I wrote more consistently and pushed myself to try new formats, new tones, to be funny in print. And it’s paying off! My subscriber count has more than doubled this year (albeit from a very small base). The number of you I don’t know personally now far outranks friends and family, which goes a long way toward making this endeavor feel like something real. I appreciate so much that any of you spend your time reading me.

This was also my first full year as a parent, which makes 2023 the best year of my life so far, period.

I am loving that this newsletter is my full-time job right now but that can’t last forever. I need to find something that actually pays the bills. I would like more than anything for this newsletter to be a viable financial proposition; please consider upgrading to paid. But even if a significant portion of you did that, there still aren’t enough of you in absolute terms—more important at this point is growing my readership. The most helpful thing you can do is share The Underline with anyone you think might enjoy it as well, so please consider doing so—go back through the archive and pick out one of the good ones maybe. (Also if any of you know how to game the Facebook algorithm so it will actually put my links in the feed, please please reach out—I get zero engagement there because it just swallows my stories into the abyss).

Thank you again. I have never felt this creatively satisfied and I can’t wait to keep going in 2024.

Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson, 1980

This was Marilynne Robinson’s first novel, which makes it the kind of achievement that should make the rest of us give up on ever trying to write anything. It tells the story of two sisters, Ruth and Lucille, who grow up in the isolated town of Fingerbone, Idaho. Their mother leaves them in their grandmother’s care and then drives her car off a cliff into the lake Fingerbone is built alongside. Ruth and Lucille’s grandfather is also in the lake, having died when a train derailed off the bridge. Their grandmother dies eventually too, at which point her two sisters briefly move in. It’s a bad fit and they quickly return to Spokane once Ruth and Lucille’s aunt Sylvie drifts back into town and tries to cast off her nomadic lifestyle and assimilate to town life.

Every sentence of Housekeeping is exquisite. Robinson writes so precisely and so vividly. Each chapter unfolds slowly, building up incident and observation until suddenly a story has taken place. Robinson hits her motifs overtly but with such a delicate touch. Water holds a central place throughout in numerous variations—the lake floods, then freezes; the girls skip school to sit on the shore and skip rocks; Sylvie takes Ruth by rowboat to the ruins of a house in the woods. Occasionally Ruth’s narration pulls back and enters a biblical register, relating her life to episodes from Genesis; I had to return my copy to the library so I can’t quote these passages but they are unbearably beautiful.

This is an extraordinary book. I read a lot of great stuff this year but this is almost certainly the best. I wish I had something more concrete to say about it, or anything at all to criticize, but I don’t. It is really something special.

Journeys of Frodo, Barbara Strachey, 1981

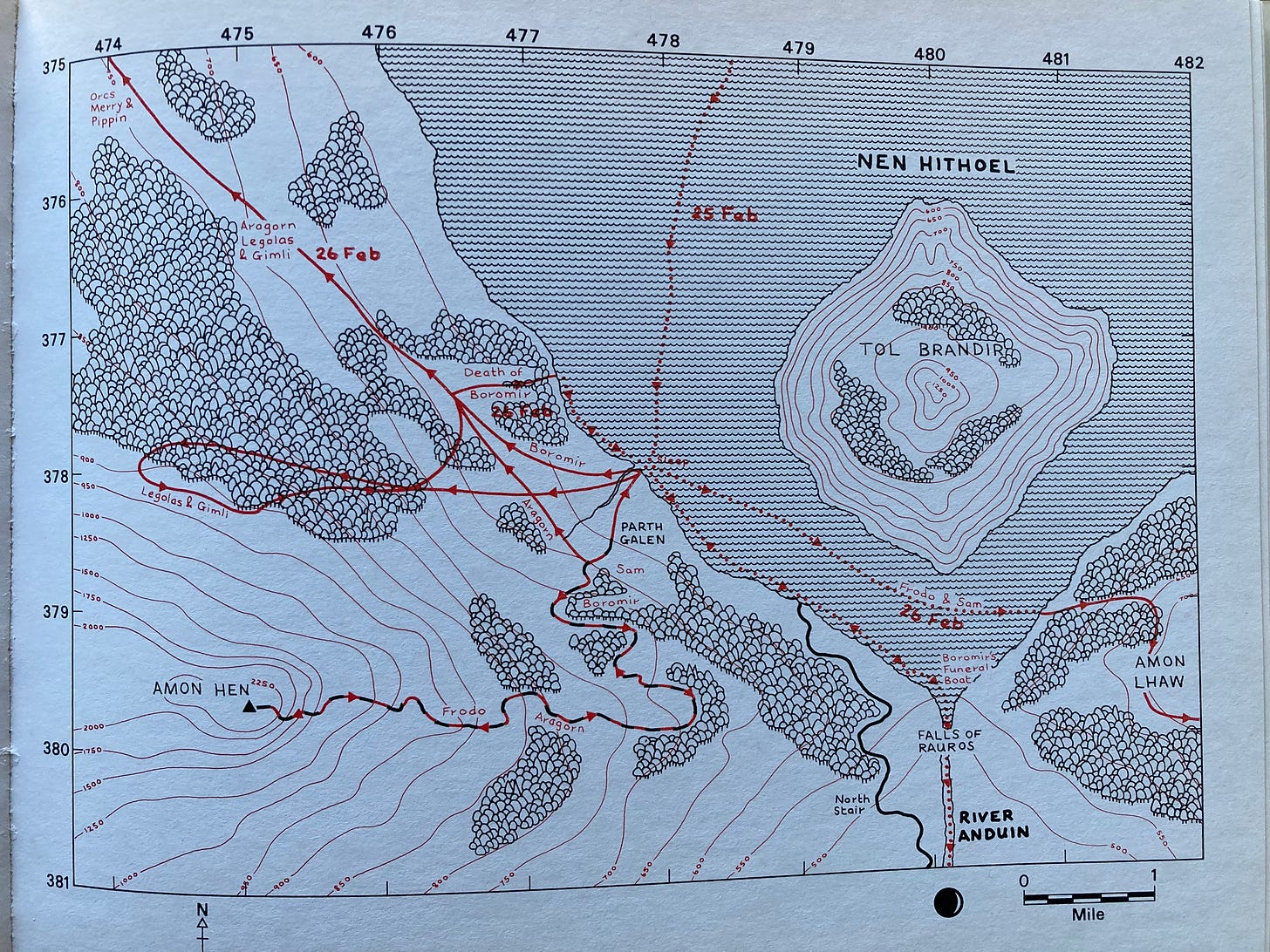

This charming little book consists of a collection of maps documenting every step of the fellowship’s journey from Hobbiton to Mordor. Strachey—yes, one of those Stracheys, the niece of Lytton and James—writes in the foreword that she was always frustrated she didn’t have a complete set of maps of Frodo’s journey and so took on the task herself. She has relied on Tolkien’s own maps for an overall picture of Middle-Earth but then compiled every piece of textual evidence to flesh out the details, frequently citing the Unfinished Tales and The Hobbit in addition to the Lord of the Rings itself.

Each map is accompanied by a few paragraphs where she presents her reasoning and her justifications for her deviations. I find this all quite fun—extremely pedantic and nerdy to be sure but in a good way. Here’s just a taste of that:

There is another point, namely the distance from Brandywine Bridge to the Ferry. When the Black Rider reached the Ferry, Merry says that to get to them he would either have to swim the river or go 20 miles north to the Bridge. (A Conspiracy Unmasked; Bk 1.) I have assumed that he meant 20 miles in all—10 miles north to the Bridge and 10 miles south on the other side. To assume that the Ferry was 20 miles south of the Bridge won't work, as then the Hedge, which is said to be 'well over 20 miles from end to end', would have had to be more like 40 or so miles long if it was to end at the confluence of the river Withywindle, as stated. (A Conspiracy Unmasked; Bk 1.)

I love it! This coffee table book for Middle-Earth sickos is sadly out of print but thankfully it is available on the Internet Archive. Here are two of my favorite maps, which I suspect were key reference points for their sections of the movie adaptations.

Shaman, Kim Stanley Robinson, 2013

I had wanted to read Robinson since Ministry for the Future made a splash as important literature about climate change. But there was a deep waitlist for it at the library so I picked something else. It was hard to know what to go for—he has a trilogy about terraforming Mars that’s acclaimed but one of my weird hang-ups is I just hate Mars, I never want to read a story about Mars. At a loss with all the speculative future stories I went the other way and picked his most different book, one about a tribe of early modern humans during the last Ice Age.

Unfortunately I didn’t care for it at all. Shaman is a pure process novel. By that I mean the story is overwhelmingly concerned with the solving of problems and completion of tasks. The book begins with Loon, a 13-year-old apprentice shaman, being sent on his wander, an initiation ceremony of sorts where he’s left alone in the wilderness with nothing and expected to survive for several weeks before returning to the tribe. This section plays out like paleolithic Hatchet, which I do not mean as a compliment. I was bored to tears by that book as a middle schooler and this was no different. I just can only read so many pages about fire-making, and frond weaving, and fish gutting before I check out.

I hoped that things would improve when he returned to camp but alas they did not. Only a couple of tribemates can rightfully be called characters and even they are thinly sketched. Robinson seems to know he needs character interaction but has a frustrating habit of setting up the situation and then veering away. When Loon goes on a hunt with two friends there’s no scene of them talking around the fire, instead it’s just more description of how to properly skin an elk.

If you were writing about primitive man, what kind of vocabulary would you adopt? We know from the fossil record that these people were anatomically identical to modern humans so they possessed all of our cognitive capacity. But there’s more to thinking and language than the abstract capacity for reasoning. That is to say, I would have thought Robinson would modulate his default analytic science vocabulary for something more fitting but he does not. When Loon assesses a potential campsite he decides it’s too close to a watering hole and so selects somewhere else in order to “minimize pass-through” from animals. I’m sorry but that just doesn’t sound like the way a caveman would phrase that! Similarly, the area he explores is divided into the Upper Valley and Lower Valley, subdivided into increasingly strained formulations like Lower’s Upper and Upper Lower. This is, first of all, just murder to read and keep straight, but it also feels wrong—it’s too relational. I imagine people of this era investing their environment with self-contained names that speak to the innate nature of a particular landmark; making everything contingent on everything around it feels particularly modern and breaks the literary effect for me. Also, at one point Loon’s mentor Thorn is exasperated and yells “Mama mia!” Look, I know these characters are not literally speaking English but come on, you can’t have an early hominid say that. Did he learn it from a tribe of Italiananderthals?