The Adventures of Lady Egeria, W.C., ~1585

Credited as the first supernatural horror novel in English, Lady Egeria is a weird one. Our titular lady is the queen of the fictional kingdom of Hetruria. If this book were better known, her husband Lampanus would be infamous as one of the most bumbling fools in all of literature. He falls under the sway of his advisor, Andromus, who flatters his way to such a position of trust that the king believes his baseless accusation that Egeria is having an affair. Egeria and her supposed lover are thrown in prison and put on trial. After much back and forth their death sentences are commuted and they are separately banished, but not before Egeria gives birth to twins, a boy with a golden thumb and a girl with a golden leg. The children are sent away to be fostered in the courts of foreign royalty. Andromus has now been joined by his sister, Eldorna, who seduces the king. When Andromus pursues Egeria as she leaves the country, he and his forces are killed by a great flock of ravens.

Years pass with our focus not on Egeria or the children but still fixed on Lampanus. Ever-deceived, he can’t see that the next flatterer who gets close to him is Eldorna’s lover. When she becomes pregnant she tells Lampanus it’s his but of course it’s not. Eventually that child, Rastophel, grows up and seizes power, Lampanus condemned to a life of penitential wandering. Rastophel, who has been trained as a necromancer, attracts a scheming advisor of his own named Spido, who betrays him to Egeria’s now-grown son Pantiper when he invades to reclaim the throne. Despite obviously being disloyal and dishonest, Spido manages to get close to Pantiper as his most trusted confidant. Lampanus ends up in the kingdom where his daughter has been raised; he attempts to rape her but is transfigured into a snake and killed. Eventually the kingdom is set right and Egeria is able to return home.

I don’t know what I was expecting here but a diatribe against the evils of fake friends was not it. By the time Pantiper is being fooled by his flatterer even the narrator seems weary of this cyclical plot point, remarking dryly that he is hardly the first liar the kingdom has suffered. The overwhelming focus on scheming viziers is perplexing. It crowds out other plot points that should be the focus. The jacket copy promises, “Murder, incest, adultery, necromancy, matricide, harlotry, betrayal, freakish twins, malign spirts, a murderous raven air force, graverobbing, even a man-to-snake metamorphosis await the fearless reader.” That’s all true, but many of those events, like the raven air force, are dealt with in a couple sentences, stated bluntly and then abandoned with no elaboration. The author, known to us only as W.C., struggles mightily with what to emphasize and how to work through plot.

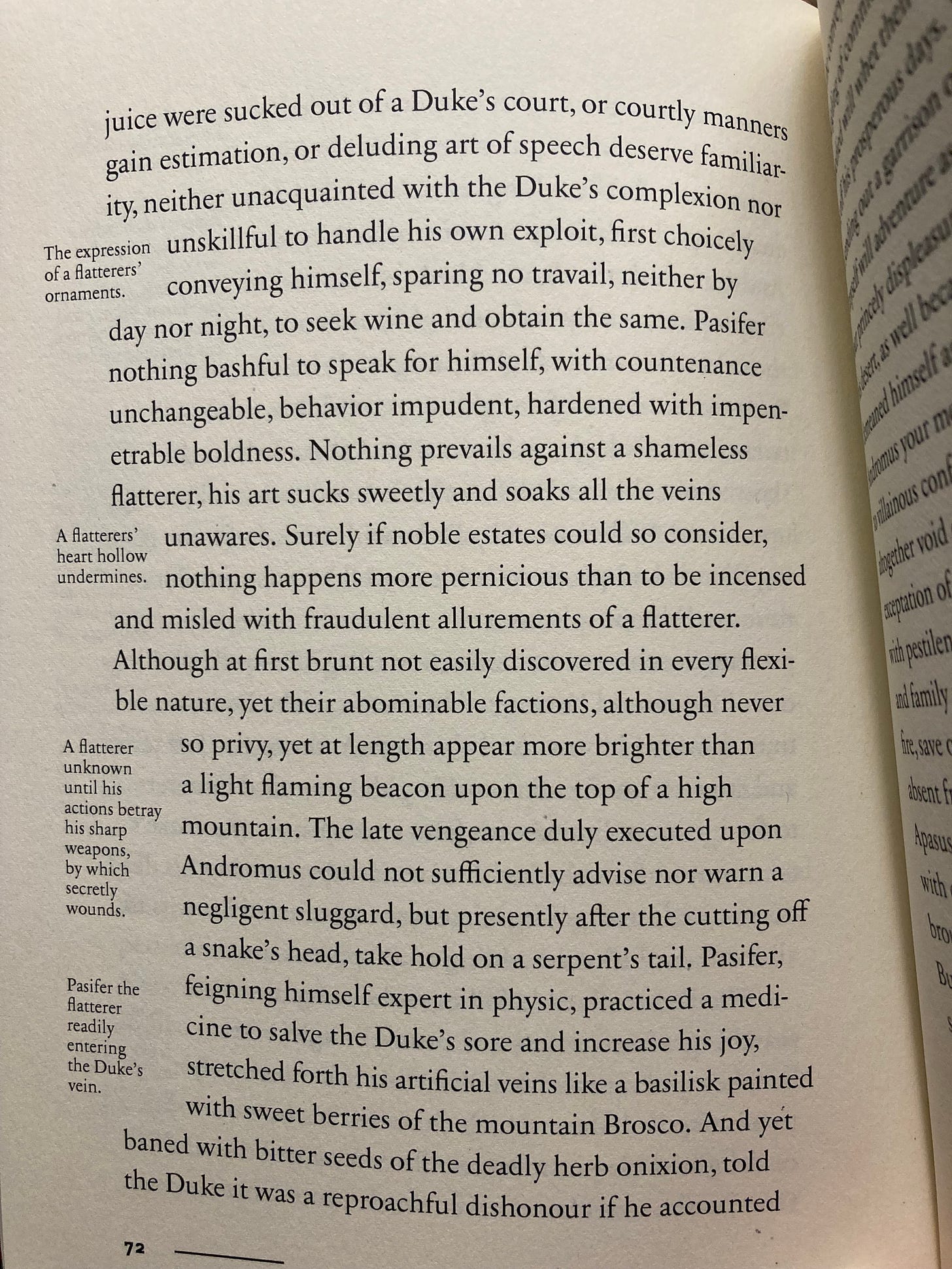

I enjoyed the frequent and idiosyncratic use of marginalia throughout. The author includes all these little asides that intrude into the paragraphs from the margins. At first they seem like glosses, a crutch for the difficult language, but they often have no obvious connection to the subject at hand or are sort of aphorisms on the general topic at hand without being connected to the specifics of the plot, as in this case:

I kind of love this? Used consistently and intentionally this could be a cool technique for running a narrative on two tracks at once, where the main text follows one character while the marginalia provides little glimpses of events happening elsewhere.

Linguistically, this is one of the most challenging books I’ve ever read. The author has a habit of leaving out pronouns and conjunctions, leading to sentences that consist of long strings of clauses separated by commas, leaving the reader to deduce the subject of each clause and their relation to each other. Sometimes this produces sentences of tremendous majesty but much of the time it results in a tangled mish-mash where a core syntax is followed by a string of obtuse clauses that don’t make sense as modifiers to the core idea. Working through language this complex can be its own reward. I found it so satisfying to notice how my mind had adjusted as I read and how much easier it was by the end. On the other hand, one would hope that the effort would be rewarded by a good story, which here is not the case.

I read this book on a whim because it was edited by the Gaddis scholar Steven Moore for the Seattle-based small press Sublunary Editions, which seems to specialize in literary curiosities and works that have been forgotten and fallen out of print. It’s a cool operation so check their selection out for yourselves.

The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns, and Fairies, Robert Kirk, ~1690

Like Lady Egeria, here’s another book I really wanted to like but whose backstory ends up more compelling than the book itself. Kirk was an Episcopalian minister in the Scottish Highlands who translated the Bible into Gaelic and collected folklore and folk practices from his parishioners about fairies, which the general population seems to have believed in. As a man of God, part of Kirk’s project is not to condemn them or disprove their existence but to demonstrate that their nature accords with certain descriptions in the Bible and that acknowledging and trusting in them presents no conflicts with doctrine or piety.

Kirk is often a beautiful writer in his own way and I found it diverting how much his writing does not follow any modern expectations to ease the reader in or give them a sense of the scope of the project up front. Instead he simply launches into a litany of fairy facts. Here is how the essay begins:

These siths or fairies they call sluagh maithe or the good people (it would seem, to prevent the dint of their ill attempts, for the Irish use to bless all they fear harm of) and are said to be of middle nature between man and angel (as were daemons thought to be of old), of intelligent studious spirits, and light changeable bodies (like those called astral) somewhat of the nature of a condensed cloud, and best seen in twilight. These bodies be so pliable through the subtlety of spirits that agitate them that they can make them appear or disappear at pleasure… Their bodies of congealed air are sometimes carried aloft, otherwhiles grovel in different shapes, and enter in any cranny or cleft of the earth (where air enters) to their ordinary dwellings, the earth being full of cavities and cells and their being no place or creature but is supposed to have other animals (greater or lesser) living in or upon it as inhabitants and no such thing as a pure wilderness in the whole universe.

Fun! As an authentic account of these beliefs, The Secret Commonwealth has immense scholarly value. But like with Lady Egeria, I found myself frustrated by what he chooses to emphasize. Kirk takes it so much for granted that general knowledge of fairies is widespread that he dispenses with describing them in only a few pages, turning to their “use” as portents for those with second sight for the majority of the essay. It should be noted that the title, bestowed when Walter Scott published it in 1815, is something of a misnomer. There are no elves or fauns discussed here—the beliefs chronicled here are exclusively about fairies. Forgive me for being a lore guy but I was hoping for something more taxonomical, a compendium of different types of spirits and their qualities and behaviors. Always I dream of the Pokedex.