My son is only two so we’re still in the picture book stage of his reading life. I should probably write about that at some point although I’m not sure what there is to say besides that Maurice Sendak was a god. In any case, I often find myself thinking ahead to when he’s older and ready for chapter books. All signs point toward him being an early and capable reader so I want to be prepared with options that will appeal to a seven or eight year old when he reaches that age.

This was a challenging period for the adults in my life in this regard. On a technical level, I was testing at a 12th grade reading level by third or fourth grade but obviously I wasn’t yet very sophisticated intellectually. I loved The Hobbit when my mom read it to me when I was around six but when we tried to move on to Lord of the Rings the chapter length and amount of landscape description was too boring to bear. I recall my fourth-grade(?) teacher somewhat desperately suggesting I read Call of the Wild by Jack London and I being baffled by it. I could read it fine but the various incidents were indistinguishable to me, the gradual process of this dog shedding its domestication totally beyond my powers of identification and nuance.

So it was with some excitement that I discovered the New York Review of Books has a dedicated kids section. This is exactly the sort of resource I need and its entire catalog is new to me. I picked out three NYRB Kids books for his birthday and recently read them myself. We’re covering those today but I’m also putting out a blanket invitation to suggest books to me for young readers. Comment your kids book recommendations down below!

Carbonel: the King of the Cats, Barbara Sleigh, 1955

Carbonel, an intensely English children’s book in the most pejorative sense, follows a girl named Rosemary who buys a cat and a broomstick from an old woman at the market who claims to be a witch. When she holds the broomstick she can understand the cat speaking to her. He’s Carbonel, a feline prince who was stolen as a kitten and bound to the witch as her familiar. Rosemary has broken the main curse on him by freeing him from the witch but now he’s bound to her. To be really free he needs Rosemary to track down the witch’s hat and cauldron so she can undo a secondary spell and allow him to reclaim his throne.

It’s unfair to call a book from the 50s video gamey but the story here really is a series of fetch quests. Worse, each of the fetch quests is the same one. The only lead Rosemary and her friend John have on the witch’s items is that she was at the market. So when they set out to find the cauldron they take the bus back to the market. They have a little adventure that involves a lot of pleading with adults and return home successful. The next day it’s time to look for the hat so what do they do? Head right back to the market and ask the same guy if he knows anything more. I’m trying to put myself in the mind of an eight year old, when taking the bus alone would feel like a huge step out into the world, but even so I’m perplexed that this story ostensibly about magic and adventure contains so little of either.

Throughout Sleigh is infuriatingly committed to keeping everything as sedate and unobjectionable as possible. When their search for the cauldron causes a teashop to erupt into chaos, John suggests they nab the cauldron and just go, stealing it. Rosemary won’t hear of it and insists they help the teashop owners with their problem. At the end of the story Rosemary casts the spell to free Carbonel and then immediately burns the witch’s spellbook. Why?? This insistence reversion to normalcy is so lame. The way this book posits a world where witchcraft and wizardry is real but is nonetheless exactly like our own is highly reminiscent of another wildly popular British children’s series that similarly suffers from the most pathetic and blinkered sense of possibility imaginable.

I am pretty sanguine about the language and attitudes you encounter in older books. Encountering outdated beliefs and offensive stereotypes is part of the tradeoff inherent in sifting through the treasures of the past. But I’ve discovered the thing I simply can’t tolerate is how mean adults are to children in books from this era. Rosemary and John are constantly berated and made to feel small by the adults around them; they spend so much of their quest just seeking to be listened to and taken seriously. At one point they’re in a candy shop run by the witch and a mother comes in with her son to complain the candy made him sick. She yells at the witch for selling bad candy and then as they’re leaving shakes her son and screams at him that she better not ever catch him eating the candy again. This sort of child abuse is just background noise. I can’t stand it.

The Little Grey Men, B.B., 1942

Now this is more like it. Ever since I read The Wind in the Willows to Patrick I’ve been looking for further reading in that vein: relaxed, pastoral, as much about the natural world as the plot. The Little Grey Men fits the bill perfectly.

Sneezewort, Baldmoney, and Dodder are the last three gnomes left in England. The previous autumn their fourth brother, Cloudberry, took a journey upstream to find the source of Folly Brook, which they live next to and fish from, and never returned. Now spring has arrived and Baldmoney and Sneezewort are determined to make a journey of their own to find Cloudberry and bring him home. Dodder, who walks on a peg leg following a fox attack, opposes their plan and won’t see them off when they finish constructing their boat but eventually relents and follows them upstream.

In the course of their adventures the gnomes will contend with nearly drowning under the waterwheel of a mill, a cruel hunter in Crow Wood, and a stranding on a desolate island. The Little Grey Men certainly features more plot and action than The Wind in the Willows but the overall impression is quite similar. B.B strikes a wonderful balance between adventure and downtime. He gives his characters space to talk and reflect in ways that don’t advance the plot and his descriptions of the natural world are beautiful. It was striking to read this back to back with Carbonel, which feels so much more rushed and frantic. Carbonel feels like it is intended for eight year olds while Little Grey Men feels like it’s for twelve year olds; the difference that makes in allowing a little slack to come into the narrative is everything. In Carbonel, the chapters are so short that it’s a real get-in-and-get-out affair—John and Rosemary state clearly what they intend to do and do it, end of chapter. When the gnomes reach Crow Wood I expected them to just plow straight through toward some further destination but instead they slow down, both to make a better search for Cloudberry and to involve themselves in the forest animals’ problems, which takes up several chapters. I appreciated this sort of variability in the structure and pacing of the story; B.B never feels hamstrung by an expectation to keep the plot moving and it always feels like he’s treating the intelligence of his young readers with respect.

Norse Gods and Giants, Ingri and Edgar Parin D’Aulaire, 1967

Between this and trying to get Ring-pilled I’m having a bit of a Norse gods winter. The D’Aulaires were a married couple who wrote and illustrated countless childrens’ books over the course of their career, first in Europe and then the United States, to which they emigrated in 1929. In 1962 they produced a lavishly illustrated compendium of Greek myths (which NYRB doesn’t seem to have the rights to but I’ll pick up eventually). They followed that template to produce this work, based on the Poetic and Prose Eddas.

It is tempting to write that the text here exists as a pretext for the illustrations but that would do it a disservice. While the illustrations are undoubtedly the main draw, there is generally more space given to text in any given spread than to the images. Having read the Poetic Edda and having found it maddeningly hard to follow given the hodge-podge nature of its compilation and the Norse penchant for kennings in place of character names, I was very impressed by the D’Aulaires’ success in rendering the Norse myths legible without simplifying them or removing the overriding strangeness of so many of them. The text of each tale is also just the right length. I can see myself reading this to Patrick one story a night before bed, with him poring over the illustrations long after I’ve finished the story.

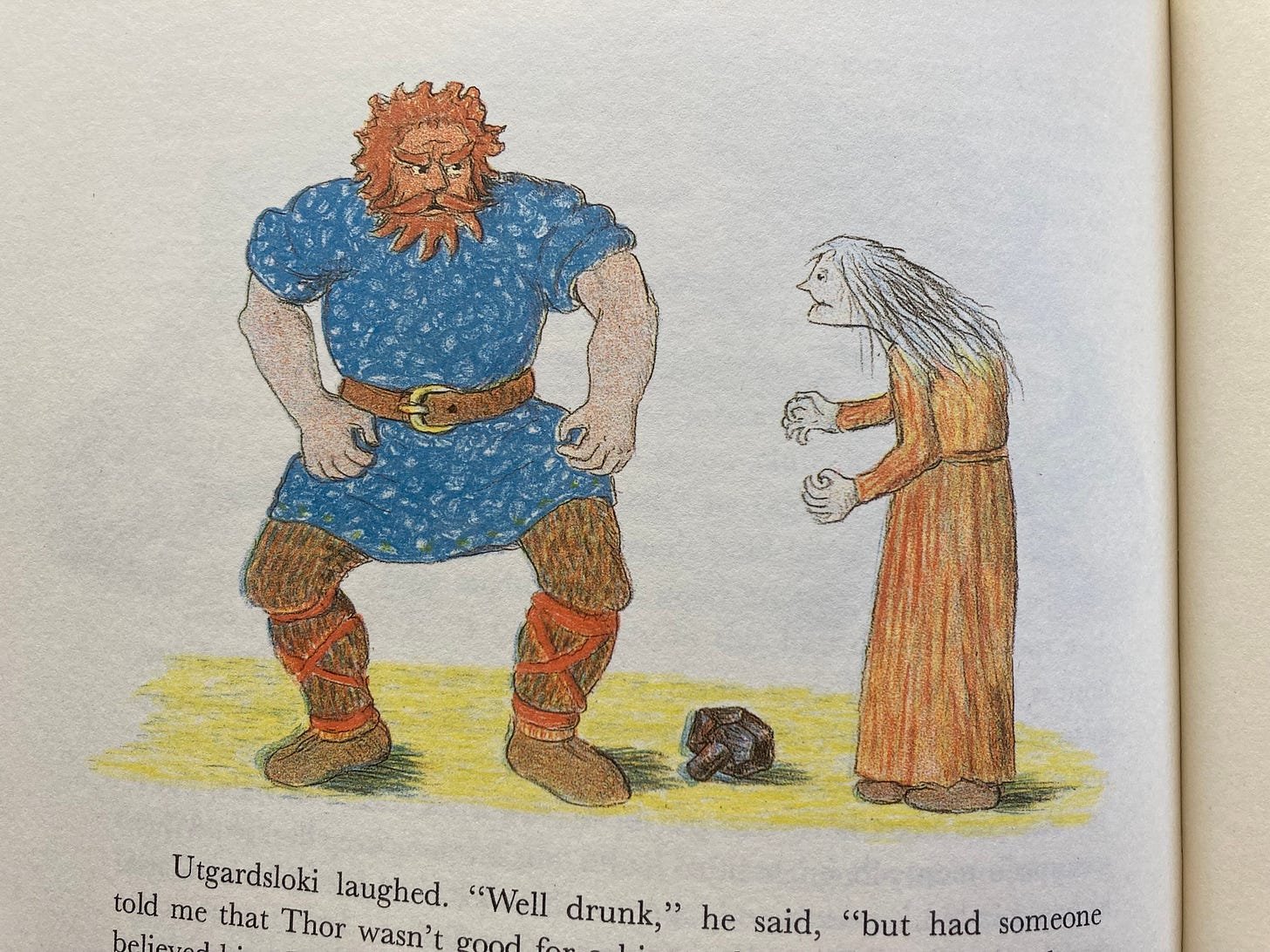

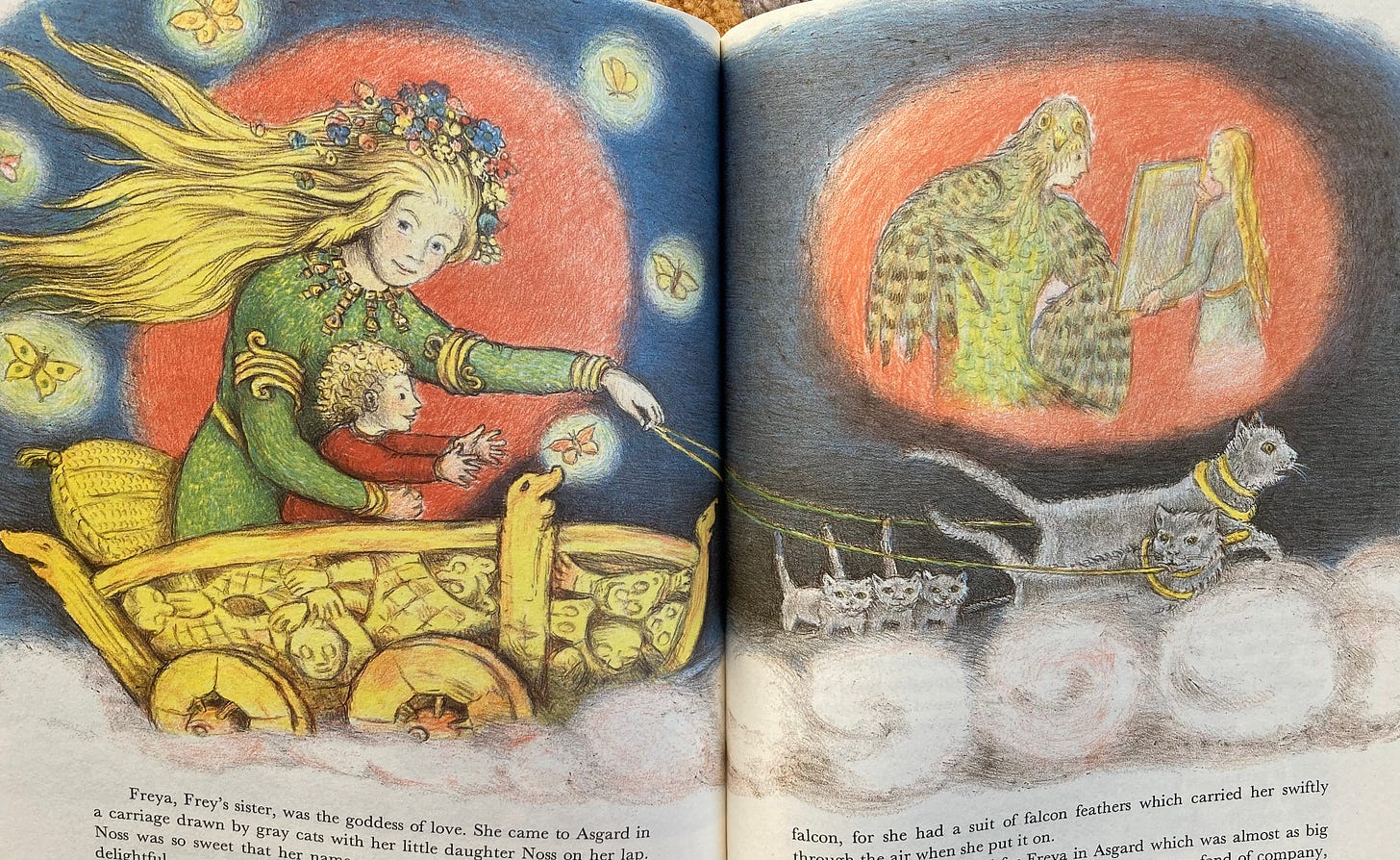

The illustrations are of course very charming. Personally I like the pictures that tend toward more figurative or abstract—their large scenes of spirits and waves are so beautiful while some of their more straightforward depictions of people are kind of doofy. Compare:

vs

Generally the D’Aulaires seem more engaged drawing women than men. Most of my favorite illustrations from the book are their loving portraits of goddesses like Sif, Freya, and Frigg. Odin, Thor, and Loki don’t fare quite as well.

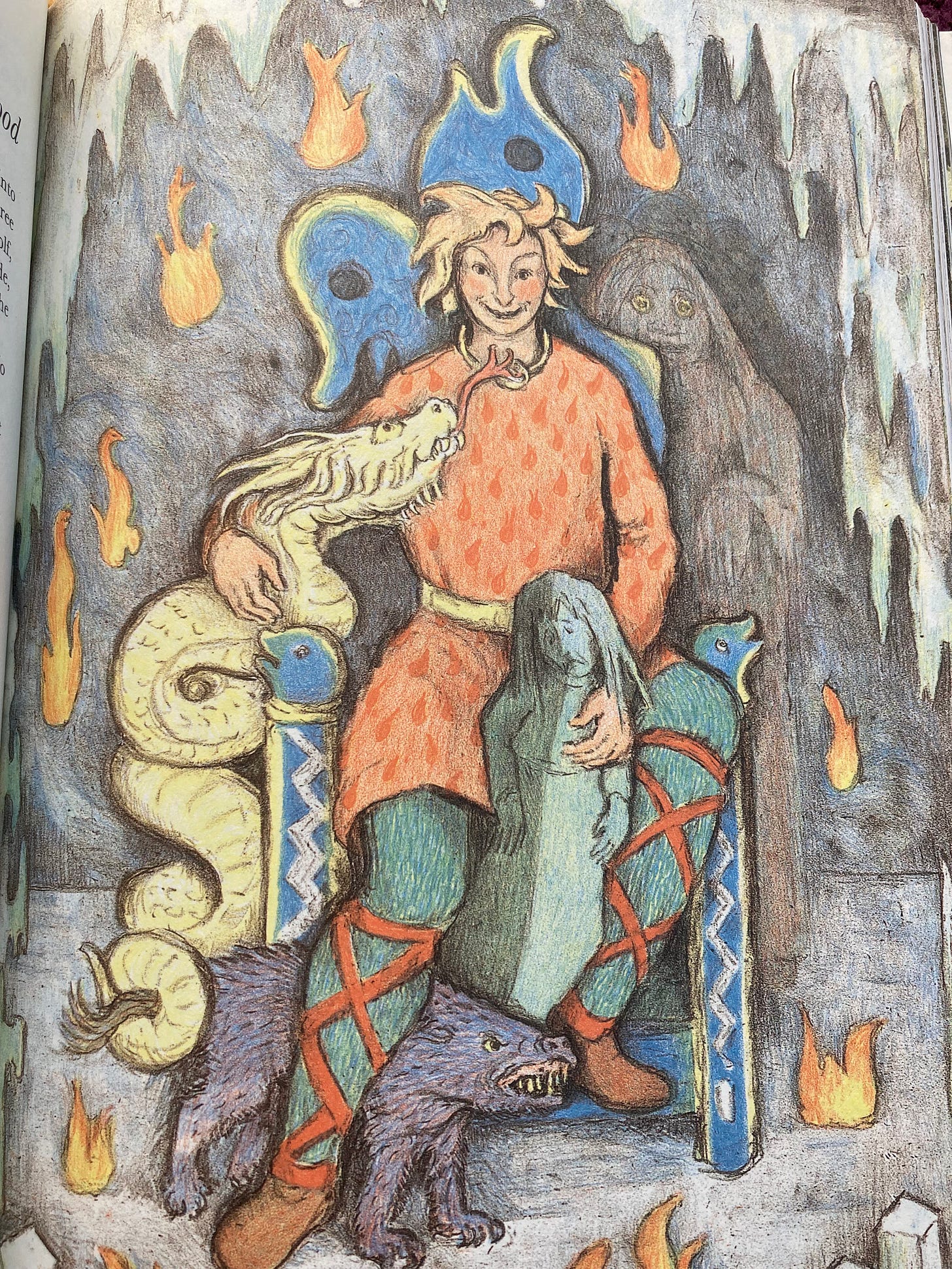

But the thing is, Odin and Loki in particular are almost impossible to visualize! Granted I have something of an image of Odin in my head—he’s basically one-eyed, somewhat shorter Gandalf—but it’s an image of him as an old man. As both this book and Das Rheingold remind us, the Norse gods depended on their special apples—kept by Idunn here and by Freya in Wagner—to preserve their eternal youth. Trying to imagine how a young Odin looks feels like a contradiction in terms but what I’m imagining is not Odin himself but his habitual disguise when he walked among men. Loki is even worse! In the production of Rheingold I watched on Youtube (the 1980 Chereau/Boulez version) they dress Loki in an old-fashioned suit with ruffles and give him a hunchback and long white hair. Wrong! Here’s how the D’Aulaires draw him:

Also wrong! I have no idea what I think Loki looks like but I know neither of these are anywhere close. It brings me great shame to say but: I think Tom Hiddleston’s Loki from the Marvel movies is probably the closest in look to whatever Platonic Form of Loki I have in mind. Is this a quality unique to the Norse pantheon? I think I have pretty definite, achievable visions of the Greek gods but I suppose that’s because Greek art was allowed to survive whereas Norse art by and large did not.

Comment your kids books recommendations down below!

Dianna Wynne Jones’s Eight Days of Luke (probably for ~12yrs) is an interesting vision of the Norse Pantheon—it shares some common quality with the D’Aulaires illustration of Loki that brought it to mind

Oddly, the cruelty to children thing is one reason I think that despite all his personal unpleasantness Roald Dahl will keep going—adults are really cruel to kids in his books and he's like yeah being a kid is all about being pushed around by these people at their convenience without ever understanding why. But maybe part of what makes that different is that the cruelty in a Dahl novel will always be pointed, it's not background noise.

I haven't read it in ages but I remember really liking the James Thurber book The 13 Clocks. Also, in picture books, the Provensens are really good… https://www.themarginalian.org/2013/03/21/william-blakes-inn-provensen/